Photoperiodism

The length of the light and dark in each phase varies across the seasons due to the tilt of the earth around its axis.

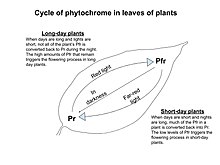

Red light (which is present during the day) converts phytochrome to its active form (Pfr) which then stimulates various processes such as germination, flowering or branching.

In comparison, plants receive more far-red in the shade, and this converts phytochrome from Pfr to its inactive form, Pr, inhibiting germination.

Experiments by Halliday et al. showed that manipulations of the red-to far-red ratio in Arabidopsis can alter flowering.

[11] Modern biologists believe[12] that it is the coincidence of the active forms of phytochrome or cryptochrome, created by light during the daytime, with the rhythms of the circadian clock that allows plants to measure the length of the night.

Other than flowering, photoperiodism in plants includes the growth of stems or roots during certain seasons and the loss of leaves.

Natural nighttime light, such as moonlight or lightning, is not of sufficient brightness or duration to interrupt flowering.

[18] Instead, they may initiate flowering after attaining a certain overall developmental stage or age, or in response to alternative environmental stimuli, such as vernalisation (a period of low temperature).

[19][20] Photoperiod can affect insects at different life stages, serving as an environmental cue for physiological processes such as diapause induction and termination, and seasonal morphs.

[21] In the water strider Aquarius paludum, for instance, photoperiod conditions during nymphal development have been shown to trigger seasonal changes in wing frequency and also induce diapause, although the threshold critical day lengths for the determination of both traits diverged by about an hour.

[24] In mammals, daylength is registered in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), which is informed by retinal light-sensitive ganglion cells, which are not involved in vision.

In most species the hormone melatonin is produced by the pineal gland only during the hours of darkness, influenced by the light input through the RHT and by innate circadian rhythms.

Many mammals, particularly those inhabiting temperate and polar regions, exhibit a remarkable degree of seasonality in response to changes in daylight hours(photoperiod).

[25] These animals undergo molting, transforming from dark summer fur to white coat in winter, that provides crucial camouflage in snowy environments.

[27] Seasonality in human birth rate appears to have largely decreased since the industrial revolution.

The fungus Neurospora crassa as well as the dinoflagellate Lingulodinium polyedra and the unicellular green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii have been shown to display photoperiodic responses.