Universe

Since the early 20th century, the field of cosmology establishes that space and time emerged together at the Big Bang 13.787±0.020 billion years ago[11] and that the universe has been expanding since then.

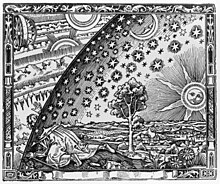

[12][13] Over the centuries, more precise astronomical observations led Nicolaus Copernicus to develop the heliocentric model with the Sun at the center of the Solar System.

At smaller scales, galaxies are distributed in clusters and superclusters which form immense filaments and voids in space, creating a vast foam-like structure.

After an initial accelerated expansion called the inflationary epoch at around 10−32 seconds, and the separation of the four known fundamental forces, the universe gradually cooled and continued to expand, allowing the first subatomic particles and simple atoms to form.

[18] There are many competing hypotheses about the ultimate fate of the universe and about what, if anything, preceded the Big Bang, while other physicists and philosophers refuse to speculate, doubting that information about prior states will ever be accessible.

[35] Synonyms are also found in Latin authors (totum, mundus, natura)[36] and survive in modern languages, e.g., the German words Das All, Weltall, and Natur for universe.

Since the Planck epoch, the universe has been expanding to its present scale, with a very short but intense period of cosmic inflation speculated to have occurred within the first 10−32 seconds.

These elementary particles associated stably into ever larger combinations, including stable protons and neutrons, which then formed more complex atomic nuclei through nuclear fusion.

The remaining two interactions, the weak and strong nuclear forces, decline very rapidly with distance; their effects are confined mainly to sub-atomic length scales.

[61][b] Assuming that the Lambda-CDM model is correct, the measurements of the parameters using a variety of techniques by numerous experiments yield a best value of the age of the universe at 13.799 ± 0.021 billion years, as of 2015.

In 1998, the deceleration parameter was measured by two different groups to be negative, approximately −0.55, which technically implies that the second derivative of the cosmic scale factor

[15] The Newtonian theory of gravity is a good approximation to the predictions of general relativity when gravitational effects are weak and objects are moving slowly compared to the speed of light.

On average, space is observed to be very nearly flat (with a curvature close to zero), meaning that Euclidean geometry is empirically true with high accuracy throughout most of the universe.

[83] Observations, including the Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE), Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP), and Planck maps of the CMB, suggest that the universe is infinite in extent with a finite age, as described by the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker (FLRW) models.

According to this hypothesis, if any of several fundamental constants were only slightly different, the universe would have been unlikely to be conducive to the establishment and development of matter, astronomical structures, elemental diversity, or life as it is understood.

The effects of this force are easily observable at the microscopic and at the macroscopic level because the photon has zero rest mass; this allows long distance interactions.

Hence, according to Einstein's field equations, R grew rapidly from an unimaginably hot, dense state that existed immediately following this singularity (when R had a small, finite value); this is the essence of the Big Bang model of the universe.

[19][159] Max Tegmark developed a four-part classification scheme for the different types of multiverses that scientists have suggested in response to various problems in physics.

Tegmark and others[168] have argued that, if space is infinite, or sufficiently large and uniform, identical instances of the history of Earth's entire Hubble volume occur every so often, simply by chance.

The modern era of cosmology began with Albert Einstein's 1915 general theory of relativity, which made it possible to quantitatively predict the origin, evolution, and conclusion of the universe as a whole.

Anaximenes proposed the primordial material to be air on account of its perceived attractive and repulsive qualities that cause the arche to condense or dissociate into different forms.

Democritus, and later philosophers—most notably Leucippus—proposed that the universe is composed of indivisible atoms moving through a void (vacuum), although Aristotle did not believe that to be feasible because air, like water, offers resistance to motion.

[183][184] The Indian philosopher Kanada, founder of the Vaisheshika school, developed a notion of atomism and proposed that light and heat were varieties of the same substance.

[194][195] Later Greek philosophers, observing the motions of the heavenly bodies, were concerned with developing models of the universe based more profoundly on empirical evidence.

For Aristotle, normal matter was entirely contained within the terrestrial sphere, and it obeyed fundamentally different rules from heavenly material.

Other Greek scientists, such as the Pythagorean philosopher Philolaus, postulated (according to Stobaeus' account) that at the center of the universe was a "central fire" around which the Earth, Sun, Moon and planets revolved in uniform circular motion.

[210] The Aristotelian model was accepted in the Western world for roughly two millennia, until Copernicus revived Aristarchus's perspective that the astronomical data could be explained more plausibly if the Earth rotated on its axis and if the Sun were placed at the center of the universe.

Roughly a century before Copernicus, the Christian scholar Nicholas of Cusa also proposed that the Earth rotates on its axis in his book, On Learned Ignorance (1440).

Edmund Halley (1720)[216] and Jean-Philippe de Chéseaux (1744)[217] noted independently that the assumption of an infinite space filled uniformly with stars would lead to the prediction that the nighttime sky would be as bright as the Sun itself; this became known as Olbers' paradox in the 19th century.

[224] The modern era of physical cosmology began in 1917, when Albert Einstein first applied his general theory of relativity to model the structure and dynamics of the universe.

(video 00:50; May 2, 2019)