Physiology of decompression

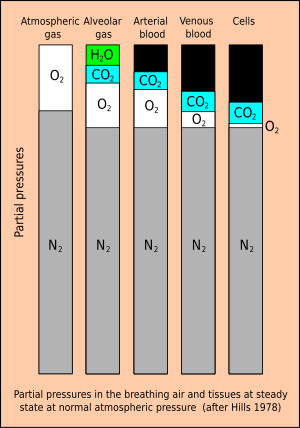

It involves a complex interaction of gas solubility, partial pressures and concentration gradients, diffusion, bulk transport and bubble mechanics in living tissues.

[2] In the study of decompression theory, the behaviour of gases dissolved in the body tissues is investigated and modeled for variations of pressure over time.

Under equilibrium conditions, the total concentration of dissolved gases will be less than the ambient pressure, as oxygen is metabolised in the tissues, and the carbon dioxide produced is much more soluble.

The development of schedules that are both safe and efficient has been complicated by the large number of variables and uncertainties, including personal variation in response under varying environmental conditions and workload.

[3] The inert gases from the breathing gas in the lungs diffuse into blood in the alveolar capillaries ("move down the pressure gradient") and are distributed around the body by the systemic circulation in the process known as perfusion.

The number of half times chosen to assume full saturation depends on the decompression model, and typically ranges from 4 (93.75%) to 6 (98.44%).

[42] Deep tissue ICD (also known as transient isobaric counterdiffusion)[44] occurs when different inert gases are breathed by the diver in sequence.

[48] They suggest that breathing-gas switches from helium-rich to nitrogen-rich mixtures should be carefully scheduled either deep (with due consideration to nitrogen narcosis) or shallow to avoid the period of maximum supersaturation resulting from the decompression.

[48] A similar hypothesis to explain the incidence of IEDCS when switching from trimix to nitrox was proposed by Steve Burton, who considered the effect of the much greater solubility of nitrogen than helium in producing transient increases in total inert gas pressure, which could lead to DCS under isobaric conditions.

[49] The spontaneous formation of nanobubbles on hydrophobic surfaces is a possible source of micronuclei, but it is not yet clear if these can grow to symptomatic dimensions as they are very stable.

[50] Decompression bubbles appear to form mostly in the systemic capillaries where the gas concentration is highest, often those feeding the veins draining the active limbs.

Some of the bubbles carried back to the heart in the veins may be transferred to the systemic circulation via a patent foramen ovale in divers with this septal defect, after which there is a risk of occlusion of capillaries in whichever part of the body they end up in.

Even without producing acute signs and symptoms, vascular gas bubbles can be an indicator of the magnitude of decompression stress, and as most dives where gas bubbles form only produce minimal symptoms, they may be useful as an indicator of the risk of injury in a particular dive, and therefore could be useful to help develop safer procedures.

[63][59] The pressure exposure history and breathing gas mixtures in combination have the greatest influence on the level of decompression stress and are the easiest set of factors to measure and quantify.

[5] work of breathing effects of gas density, exertion, and dehydration, which causes reduced blood volume and increased concentration of solutes in what remains.

[66][59][67] The dive profile has the greatest influence on the level of decompression stress in divers, and is the easiest set of factors to measure and quantify.

Decompression stops provide the time required for outgassing to reduce concentrations to levels calculated to be acceptably safe, before ascent is continued.

A diver who is warm will be more thoroughly perfused than a cold diver, and perfusion of particular tissues and organs will affect the amount of inert gas available for dissolving in those tissues during the ingassing part of the dive, and similarly, will affect the transport of excess dissolved gas to the lungs where it can be eliminated during the decompression stages of the dive.

It may be possible by analysing the diving history of the individual to identify ways to reduce future risk, though this is not always the case, as some hits are not amenable to confident explanation.

[39] While circulation is clearly a factor in the physiology of decompression, as perfusion is recognised as a limiting factor in dissolved gas transport to and from the tissues, and in the transport and distribution of vascular bubbles during decompression, there is little empirical evidence of altered risk due to compromised circulation due to prior injury, body positioning, or even dehydration.

Genetic predisposition and epigenetic expression affect various aspects of physiology, and may influence susceptibility and response to decompression stress, but this has not yet been studied.

[39][70] Based on observations in the field, Pyle (2001) has hypothesized that some behavioural factors at the end of deep technical dives may influence decompression stress and the risk of developing symptoms shortly after exit from the water.

Vascular bubbles appear to form at the venous end of capillaries and pass through the veins to the right side of the heart, and thereafter are circulated to the lungs.

Barotrauma of decompression generally manifests as sinus or middle ear effects, lung overpressure injuries and overexpansion of gases in the gastrointestinal tract.

Ebullism is the formation of water vapour bubbles in bodily fluids due to reduced environmental pressure, usually at extreme high altitude.

It is a long process during which inert gases are eliminated at a very low rate limited by the slowest affected tissues, and a deviation from schedule that reduces pressure more rapidly can cause the formation of gas bubbles which can produce decompression sickness.

In 2015 a concept named Extended Oxygen Window was used in preliminary tests for a modified saturation decompression model.

The water vapour may bloat the body to twice its normal volume and slow circulation, but tissues are elastic and strong enough to prevent rupture.

[90] Other early work on Doppler detection of inert gas bubbles in decompression was done by Alf O. Brubakk, at the Norwegian Underwater Institute.

[93] An absence of detectable pulmonary arterial bubbles is a strong indicator that any clinical signs or symptoms that may manifest are not caused by DCS.