Pied Piper of Hamelin

The earliest references describe a piper, dressed in multicoloured ("pied") clothing, who was a ratcatcher hired by the town to lure rats away[1] with his magic pipe.

This version of the story spread as folklore and has appeared in the writings of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the Brothers Grimm, and Robert Browning, among others.

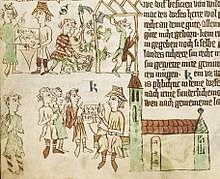

On Saint John and Paul's day, while the adults were in church, the piper returned, dressed in green like a hunter and playing his pipe.

[4] Other versions relate that the Pied Piper led the children to the top of Koppelberg Hill, where he took them to a beautiful land,[5] or a place called Koppenberg Mountain,[6] or Transylvania.

[12] Decan Lude of Hamelin was reported c. 1384 to have in his possession a chorus book containing a Latin verse giving an eyewitness account of the event.

[14] An article by James P. O'Donnell in The Saturday Evening Post (December 24, 1955) tells how an elderly German researcher, Heinrich Spanuth, discovered the earliest version of the story in the Luneberg city archives in 1936.

A certain young man thirty years of age, handsome and well-dressed, so that all who saw him admired him because of his appearance, crossed the bridges and entered the town by the West Gate.

[16][17][18][note 1]It is rendered in the following form in an inscription on a house in Hamelin known as the Rattenfängerhaus (Ratcatcher's House):[14] anno 1284 am dage johannis et pauli war der 26. juni dorch einen piper mit allerley farve bekledet gewesen cxxx kinder verledet binnen hameln geboren to calvarie bi den koppen verloren (In the year 1284 on the day of [Saints] John and Paul on 26 June 130 children born in Hamelin were lured by a piper clothed in many colours to Calvary near the Koppen, [and] lost) According to author Fanny Rostek-Lühmann this is the oldest surviving account.

[19] A similar inscription can be found on the Hochzeitshaus (Wedding House), a fine structure erected between 1610 and 1617[20] for marriage festivities, but diverted from its purpose since 1721.

Behind rises the spire of the parish church of St. Nicholas which, in the words of an English book of folklore, may still "enwall stones that witness how the parents prayed, while the Piper wrought sorrow for them without":[21] Nach Christi Geburt 1284 Jahr Gingen bei den Koppen unter Verwahr Hundert und dreissig Kinder, in Hameln geboren von einem Pfeiffer verfürt und verloren In the year of Our Lord 1284 went into the Koppen under custody 130 children born in Hamelin by a piper seduced and lost A portion of the town gate dating from the year 1556 is currently exhibited at the Hamelin Museum.

[22] It bears the following inscription:[23] Anno 1556 / Centu[m] ter denos C[um] mag[us] ab urbe puellos / Duxerat a[n]te a[n]nos 272.

The Hamelin Museum writes:[24]In the mid 14th Century, a monk from Minden, Heinrich von Herford, puts together a collection of holy legends called the "Catena Aurea".

[25] Another was included by Johann Daniel Gottlieb Herr under the title Passionale Sanctorum in Collectanea zur Geschichte der Stadt Hameln.

Post duo C. C. mille post octoginta quaterue —Annus hic est ille, quo languet sexus uterque— Orbantis pueros centumque triginta Joannis Et Pauli caros Hamelenses non sine damnis, Fatur, ut omnes eos vivos Calvaria sorpsit, Christi tuere reos, ne tam mala res quibus obsit.

Anno millesimo ducentesimo octuagesimo quarto in die Johannis et Pauli perdiderunt Hamelenses centum et triginta pueros, qui intraverunt montem Calvariam.

Some of the scenarios that have been suggested as fitting this theory include that the children drowned in the river Weser, were killed in a landslide or contracted some disease during an epidemic.

Another modern interpretation reads the story as alluding to an event where Hamelin children were lured away by a pagan or heretic sect to forests near Coppenbrügge (the mysterious Koppen "hills" of the poem) for ritual dancing where they all perished during a sudden landslide or collapsing sinkhole.

[31] Speculation on the emigration theory is based on the idea that, by the 13th century, overpopulation of the area resulted in the oldest son owning all the land and power (majorat), leaving the rest as serfs.

[citation needed] In his book The Pied Piper: A Handbook, Wolfgang Mieder states that historical documents exist showing that people from the area including Hamelin did help settle parts of Transylvania.

"[34] Transylvania had suffered under lengthy Mongol invasions of Central Europe, led by two grandsons of Genghis Khan and which date from around the time of the earliest appearance of the legend of the piper, the early 13th century.

[35] In the version of the legend posted on the official website for the town of Hamelin, another aspect of the emigration theory is presented: Among the various interpretations, reference to the colonization of East Europe starting from Low Germany is the most plausible one: The "Children of Hameln" would have been in those days citizens willing to emigrate being recruited by landowners to settle in Moravia, East Prussia, Pomerania or in the Teutonic Land.

[36]The theory is provided credence by the fact that family names common to Hamelin at the time "show up with surprising frequency in the areas of Uckermark and Prignitz, near Berlin.

The bishops and dukes of Pomerania, Brandenburg, Uckermark and Prignitz sent out glib "locators", medieval recruitment officers, offering rich rewards to those who were willing to move to the new lands.

Indeed there are five villages called Hindenburg running in a straight line from Westphalia to Pomerania, as well as three eastern Spiegelbergs and a trail of etymology from Beverungen south of Hamelin to Beveringen northwest of Berlin to Beweringen in modern Poland.

Professor Udolph can show that the Hamelin exodus should be linked with the Battle of Bornhöved in 1227 which broke the Danish hold on Eastern Europe.

That opened the way for German colonization, and by the latter part of the thirteenth century there were systematic attempts to bring able-bodied youths to Brandenburg and Pomerania.

"[68] This proverb, in contrast to the modern interpretation of paying a debt, suggests that the person who bears the financial responsibility for something also has the right to determine how it should be carried out.

Interest in the city's connection to the story remains so strong that, in 2009, Hamelin held a tourist festival to mark the 725th anniversary of the disappearance of the town's earlier children.

[71] The city also maintains an online shop with rat-themed merchandise as well as offering an officially licensed Hamelin Edition of the popular board game Monopoly which depicts the legendary Piper on the cover.