Pieter Bruegel the Elder

After his training and travels to Italy, he returned in 1555 to settle in Antwerp, where he worked mainly as a prolific designer of prints for the leading publisher of the day.

His painting Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, now thought only to survive in copies, is the subject of the final lines of the 1938 poem "Musée des Beaux Arts" by W. H. Auden.

[8] The two main early sources for Bruegel's biography are Lodovico Guicciardini's account of the Low Countries (1567) and Karel van Mander's 1604 Schilder-boeck.

[12] In contrast, scholars of the last six decades have emphasised the intellectual content of his work, and conclude: "There is, in fact, every reason to think that Pieter Bruegel was a townsman and a highly educated one, on friendly terms with the humanists of his time",[13] ignoring van Mander's dorp and just placing his childhood in Breda itself.

[16] Before this, Bruegel was already working in Mechelen, where he is documented between September 1550 and October 1551 assisting Peeter Baltens on an altarpiece (now lost), painting the wings in grisaille.

He visited Rome and, rather adventurously for the period, by 1552 had reached Reggio Calabria at the southern tip of the mainland, where a drawing records the city in flames after a Turkish raid.

[21] All the drawings from the trip that are considered authentic are of landscapes; unlike most other 16th-century artists visiting Rome he seems to have ignored both classical ruins and contemporary buildings.

[22] From 1555 until 1563, Bruegel lived in Antwerp, then the publishing centre of northern Europe, mainly working as a designer of over forty prints for Cock, though his dated paintings begin in 1557.

His paintings were much sought after, with patrons including wealthy Flemish collectors and Cardinal Granvelle, in effect the Habsburg chief minister, who was based in Mechelen.

In 1517, about eight years before Bruegel's birth, Martin Luther created his Ninety-five Theses and began the Protestant Reformation in neighbouring Germany.

The Habsburg monarchs of Spain attempted a policy of strict religious uniformity for the Catholic Church within their domains and enforced it with the Inquisition.

Increasing religious antagonisms and riots, political manoeuvrings, and executions eventually resulted in the outbreak of the Eighty Years' War.

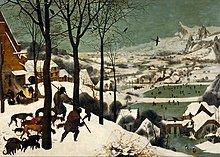

His earlier style shows dozens of small figures, seen from a high viewpoint, and spread fairly evenly across the central picture space.

The setting is typically an urban space surrounded by buildings, within which the figures have a "fundamentally disconnected manner of portrayal", with individuals or small groups engaged in their own distinct activity, while ignoring all the others.

For example, his famous painting Netherlandish Proverbs, originally The Blue Cloak, illustrates dozens of then-contemporary aphorisms, many of which still are in use in current Flemish, French, English and Dutch.

Bruegel also painted religious scenes in a wide Flemish landscape setting, as in the Conversion of Paul and The Sermon of St. John the Baptist.

Examples include paintings such as The Fight Between Carnival and Lent (a satire of the conflicts of the Protestant Reformation) and engravings like The Ass in the School and Strongboxes Battling Piggybanks.

At his "House of the Four Winds" Cock ran a production and distribution operation efficiently turning out prints of many sorts that was more concerned with sales than the finest artistic achievement.

[41] Among his greatest successes were a series of allegories, among several designs adopting many of the very individual mannerisms of his compatriot Hieronymus Bosch: The Seven Deadly Sins and The Virtues.

After a considerable purge of attributions in recent decades, led by Hans Mielke,[13] sixty-one sheets of drawings are now generally agreed to be by Bruegel.

Mielke's key observation was that the lily watermark on the paper of several sheets was only found from around 1580 onwards, which led to the rapid acceptance of his proposal.

His friend Abraham Ortelius described him in a friendship album in 1574 as "the most perfect painter of his century", but both Vasari and Van Mander see him as essentially a comic successor to Hieronymus Bosch.

[47] As well as being forward-looking, his art reinvigorates medieval subjects such as marginal drolleries of ordinary life in illuminated manuscripts, and the calendar scenes of agricultural labours set in landscape backgrounds, and puts these on a much larger scale than before, and in the expensive medium of oil painting.

As well as the general conception of such kermis subjects, Vinckboons and other artists took from Bruegel "such stylistic devices as the bird's-eye perspective, ornamentalised vegetation, bright palette, and stocky, odious figures.

[28] The critical treatment of Bruegel as essentially an artist of comic peasant scenes persisted until the late 19th century, even after his best paintings became widely visible as royal and aristocratic collections were turned into museums.

[13] Even Henri Hymans, whose work of 1890/1891 was the first important contribution to modern Bruegel scholarship, could describe him thus: "His field of enquiry is certainly not of the most extensive; his ambition, too, is modest.

His painting Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, now thought only to survive in copies, is the subject of the final lines of the 1938 poem "Musée des Beaux Arts" by W. H. Auden: In Brueghel's Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry, But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky, Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

Michael Frayn's novel Headlong, imagines a lost panel from the 1565 Months series resurfacing unrecognised, which triggers a conflict between an art (and money) lover and the boor who possesses it.

It is believed that the painting The Hunters in the Snow influenced the classic short story with the same title written by Tobias Wolff and featured in In the Garden of the North American Martyrs.

In the foreword to his novel The Folly of the World, author Jesse Bullington explains that Bruegel's painting Netherlandish Proverbs inspired the title and also the plot to some extent.