The Pilgrim's Progress

[10] According to literary editor Robert McCrum, "there's no book in English, apart from the Bible, to equal Bunyan's masterpiece for the range of its readership, or its influence on writers as diverse as William Hogarth, C. S. Lewis, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Charles Dickens, Louisa May Alcott, George Bernard Shaw, William Thackeray, Charlotte Bronte, Mark Twain, John Steinbeck and Enid Blyton.

Bunyan began his work while in the Bedfordshire county prison for violations of the Conventicle Act 1664, which prohibited the holding of religious services outside the auspices of the established Church of England.

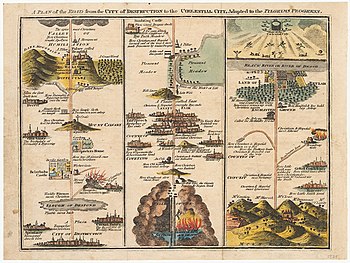

After struggling to the other side of the slough, Christian is pulled out by Help, who has heard his cries and tells him the swamp is made out of the decadence, scum, and filth of sin, but the ground is good at the narrow Wicket Gate.

Worldly Wiseman into seeking deliverance from his burden through the Law, supposedly with the help of a Mr. Legality and his son Civility in the village of Morality, rather than through Christ, allegorically by way of the Wicket Gate.

Evangelist exposes Worldly Wiseman, Legality, and Civility for the frauds they are: they would have the pilgrim leave the true path by trusting in his own good deeds to remove his burden.

Afterward, a false pilgrim named By-Ends and his friends, who followed Christian and Hopeful only to take advantage of them, perish at the Hill Lucre, never to be seen or heard from again.

On a rough, stony stretch of road, Christian and Hopeful leave the highway to travel on the easier By-Path Meadow, where a rainstorm forces them to spend the night.

The Giant and the Giantess want them to commit suicide, but they endure the ordeal until Christian realizes that a key he has, called Promise, will open all the doors and gates of Doubting Castle.

Christian and Hopeful come to a place where a man named Wanton Professor is chained by the ropes of seven demons who take him to a shortcut to the Lake of Fire (Hell).

On the way, Christian and Hopeful meet a lad named Ignorance, who believes that he will be allowed into the Celestial City through his own good deeds rather than as a gift of God's grace.

Honest, Mr. Feeble-Mind, Mr. Ready-To-Halt, Phoebe, Grace, and Martha come to Bypath-Meadow and, after much fight and difficulty, slay the cruel Giant Despair and the wicked Giantess Diffidence, and demolish Doubting Castle for Christian and Hopeful who were oppressed there.

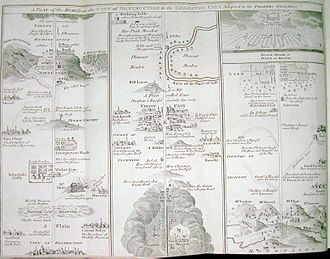

[citation needed] At least twenty-one natural or man-made geographical or topographical features from The Pilgrim's Progress have been identified—places and structures John Bunyan regularly would have seen as a child and, later, in his travels on foot or horseback.

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Religious Tract Society produced the book into Sunday School prize editions and cheap abridgments.

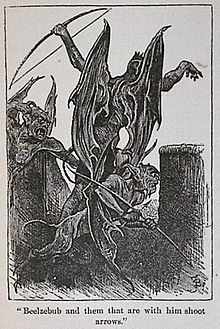

Bunyan presents a decrepit and harmless giant to confront Christian at the end of the Valley of the Shadow of Death that is explicitly named "Pope":Now I saw in my Dream, that at the end of this Valley lay blood, bones, ashes, and mangled bodies of men, even of Pilgrims that had gone this way formerly: And while I was musing what should be the reason, I espied a little before me a Cave, where two Giants, Pope and Pagan, dwelt in old times, by whose Power and Tyranny the Men whose bones, blood ashes, &c. lay there, were cruelly put to death.

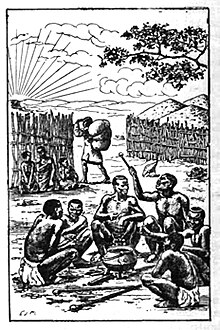

[49] Beginning in the 1850s, illustrated versions of The Pilgrim's Progress in Chinese were printed in Hong Kong, Shanghai and Fuzhou and widely distributed by Protestant missionaries.

The book was the basis of a condensed radio adaptation, originally presented in 1942 and starring John Gielgud, which included, as background music, several excerpts from Ralph Vaughan Williams' orchestral works.

A number of illustrations created by Henry Melville appear in the Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Books under the editorship of Letitia Elizabeth Landon.

These plates are as follows: The Pilgrim's Progress was a favourite subject among painters in 1840s America, including major figures of the Hudson River School and others associated with the National Academy of Design.

Daniel Huntington, Jasper Cropsey, Frederic Edwin Church, Jesse Talbot, Edward Harrison May, and others completed canvases based on the work.

[63] In 1850, Huntington, Cropsey, and Church contributed designs to a moving panorama based on The Pilgrim's Progress, conceptualized by May and fellow artist Joseph Kyle, which debuted in New York and travelled all over the country.

Hawthorne's novel The Scarlet Letter also makes reference to it, by way of the author John Bunyan with a metaphor comparing a main character's eyes with the fire depicted in the entrance to Hell in The Pilgrim's Progress.

Alan Moore, in his League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, enlists The Pilgrim's Progress protagonist, Christian, as a member of the earliest version of this group, Prospero's Men, having become wayward on his journey during his visit in Vanity Fair, stepping down an alleyway and found himself in London in the 1670s, and unable to return to his homeland.

[citation needed] In Louisa May Alcott's Little Women, the protagonist Jo and her sisters read it at the outset of the novel, and try to follow the good example of Bunyan's Christian.

[70] Walt Willis and Bob Shaw's classic science fiction fan novelette, The Enchanted Duplicator, is explicitly modeled on The Pilgrim's Progress and has been repeatedly reprinted over the decades since its first appearance in 1954: in professional publications, in fanzines, and as a monograph.

Steinbeck's novel was itself an allegorical spiritual journey by Tom Joad through America during the Great Depression, and often made Christian allusions to sacrifice and redemption in a world of social injustice.

The book was commonly referenced in African American slave narratives, such as "Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom" by Ellen and William Craft, to emphasize the moral and religious implications of slavery.

[71] Hannah Hurnard's novel Hinds' Feet on High Places (1955) uses a similar allegorical structure to The Pilgrim's Progress and takes Bunyan's character Much-Afraid as its protagonist.

In Lois McMaster Bujold's The Borders of Infinity (1989), Miles Vorkosigan uses half a page torn from The Pilgrim's Progress as a coded message to his fleet to rescue him and 9,000 others from a POW camp.

Sir Walter Scott uses Bunyan's tale in chapter 32 of his novel The Heart of Midlothian (1818) to illustrate the relationship between Madge Wildfire and Jeanie Deans.

Madge explains: "But it is all over now.—But we'll knock at the gate and then the keeper will admit Christiana, but Mercy will be left out—and then I'll stand at the door trembling and crying, and then Christiana—that's you, Jeanie,—will intercede for me.