Pinhole camera

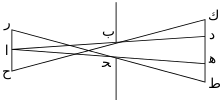

Light from a scene passes through the aperture and projects an inverted image on the opposite side of the box, which is known as the camera obscura effect.

Over the centuries others started to experiment with it, mainly in dark rooms with a small opening in shutters, mostly to study the nature of light and to safely watch solar eclipses.

[4] Giambattista Della Porta wrote in 1558 in his Magia Naturalis about using a concave mirror to project the image onto paper and to use this as a drawing aid.

In the 17th century, the camera obscura with a lens became a popular drawing aid that was further developed into a mobile device, first in a little tent and later in a box.

Eugène Estanave experimented with integral photography, exhibiting a result in 1925 and publishing his findings in La Nature.

Modern manufacturing has enabled the production of high quality pinhole lenses[12] which may be used with digital cameras.

Instructions for building a pinhole camera were published by Kodak, using either a 126 film cartridge or an empty can.

A flap of cardboard covering the pinhole, hinged with a piece of adhesive tape, can be used as a shutter.

[13] The interior of an effective pinhole camera is painted black to suppress internal stray light reflections.

Moving the film closer to the pinhole will result in a wide angle field of view and shorter exposure time.

Moving the film farther away from the pinhole will result in a telephoto or narrow-angle view and longer exposure time.

As a result of the enormous increase in f-number, to maintain similar exposure times, the photographer must use a fast film in direct sunshine or other bright light conditions.

Use with a digital SLR allows metering and composition by trial and error, and since development is effectively free, it is a popular way to try pinhole photography.

An extremely small hole, however, can produce significant diffraction effects and a less clear image due to the wave properties of light.

The best pinhole is perfectly round (since irregularities cause higher-order diffraction effects) and in an extremely thin piece of material.

But due to some incorrect and arbitrary deductions he arrived at:[18][19] So his optimal pinhole was approximatively 41% bigger than Petzval's.

Another optimum pinhole size, proposed by Young (1971), uses the Fraunhofer approximation of the diffraction pattern behind a circular aperture,[20] resulting in: This may be simplified to:

, assuming that d and f are measured in millimetres and λ is 550 nm, corresponding to the central (yellow-green) wavelength of visible light.

[citation needed] The relation f = s2/λ yields an optimum pinhole diameter d = 2√fλ, so the experimental value differs slightly from the estimate of Petzval, above.

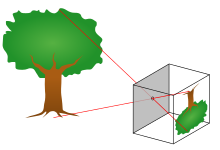

Small "pinholes" formed by the gaps between overlapping tree leaves will create replica images of the sun on flat surfaces.

Disco balls can also function as natural reflective pinhole cameras (also known as a pinhead mirror).