Piracy in the Atlantic World

In the mercantile economy of the Atlantic world, piracy emerged as a profitable venture targeting the trade routes that made European colonization possible.

Defying traditional alliances, pirates attacked and captured merchant vessels of all nations, disrupting trade routes and creating a crisis within the emerging Atlantic-centered economic system.

Although scholars agree that there was a boom in raiding and pillaging activities in the early eighteenth century, there are various schools of thought regarding the length of time that was the Golden Age.

Drake raided Spanish settlements and shipping in the South Sea shores of present-day Peru, Chile, Brazil, and Venezuela, along the coasts of Central America.

A sailor could make roughly one to one and a half thousand dollars in current pay, which back in the eighteenth century was a fairly large sum of money for a single trip.

[1]: 30–31 Frick argues that the "near-autonomous nature of a feral city" combined with its "geographic position accessible to the world's oceans" creates an ideal environment for conducting acts of piracy.

[28] Munster's coast provided favorable geography in the form of harbors, bays, islands, anchorages and headlands, while the province's remoteness made it difficult to control from London or Dublin.

This smaller percentage was due to the fact that by the time a man reached his 30s, he often transitioned to a different occupation on land, turned to fishing, labored on the docks, or had been lost at sea.

Both are risky and dangerous, and gave an individual the chance to make many decisions of their own accord.."[31] Hans Turley argues mutiny was common on long voyages and often discipline was brutal if captains heard discussions of revolt even though these actions were a serious offense due to the "direct assault on the order – thus the status quo – on a seagoing vessel."

[1]: 26 In contrast to the egalitarian belief towards mutiny, Peter Leeson argues, the "prospect of sufficient gain" may influence a sailor; piracy could pay extremely well sometimes better than privateering.

This practice often led to high rates of desertion and decreased morale, particularly in the British Royal Navy, where some impressed sailors subsequently joined pirate crews.

Historian Denver Brunsman notes that "the vast majority of impressments in colonial regions involved small numbers of seamen, mostly to replace the diseased, deserted, or deceased."

While this was not standard practice in the early Golden Age of Piracy, by the 1720s, pirate crews increasingly resorted to impressment due to a shortage of seamen willing to join voluntarily.

[1]: 48–49 When Blackbeard captured the French slave ship La Concorde in 1717 and renamed her Queen Anne's Revenge, he forcibly retained several skilled crew members.

Their size allowed for easier and quicker careening compared to larger ships, which was particularly beneficial for pirate crews unable to access dry docks or afford extended periods for maintenance.

[40] This vessel was originally mastered by Henry Bostock (1717) and captured by Blackbeard on December 5, 1717[41]: 217 and what was found on it was a "smaller two cannon exhibited inscriptions", which revealed that one was manufactured in England" and the other in Sweden.

[42]: 183–184 Wayne R. Lusardi argues there is "considerable reasonable doubt" for the ships identification and Blackbeard's flagship, and if it is Queen Anne's Revenge, the "artifact assemblage does not reflect" in any way a "distinctly piratical material culture."

Lusardi also states the idea of a pirate leaving small arms and ammunition on a grounded vessel is perplexing, yet "many abandoned items occur in the archaeological record.

"[39]: 279 There are a few differences in weaponry between pirates and men-of-war but one in particular are hand grenades which were "hollow cannonballs filled with black powder" and "pierced with a circular hole" in which a "bamboo tube was inserted" to serve as a "conduit for the fuse.

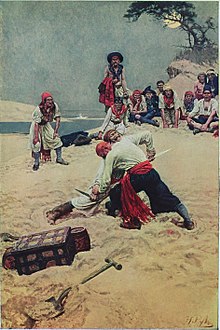

Also, personal weaponry such as pistols, cutlasses, and knives would be found on any vessel,[39]: 280 which Rediker argues was used to "slit the noses of captives, cut off ears" and used the "knife and gun against their victims.

The renown of pirates was not solely based on or confined to the co-opting of disciplinary tactics commonly used by the men sailing with official commission, but also due to their habit of "destroying massive amounts of property" with impunity.

Dutch Sea Rover of the seventeenth century, Joris Van Speilbergen and the expeditions leaders dined on "Beef, pork, fowl, citrus, fruits, preserves, olives, capers, wines, and beer," while the common crew of that voyage "scrounged herbs" with mussels and berries.

"[31]: 80 Pirates, like privateers, were a little better off than those who worked on merchant or naval ships as "food was superior," "pay was higher," "shifts were shorter," and the crew's powers of "decision making was greater."

"[13]: 164 In the book Rum, Sodomy, and the Lash, Hans Turley delves into the implications of the multidimensional threat pirates posed to the social and economic establishment within British realm.

[1]: 151–153 Prior to the mid-17th century, how Atlantic pirates were treated under the law broadly adhered to a 1559 treaty between France and Spain which laid out the "no peace beyond the line" rule, meaning that hostilities in New World waters (anything west of the Azores) was not governed by European norms.

At yet another trial in London the pirate John Bayley comically played dumb when the Judge asked what he would have done if the warship that apprehended him was nothing more than a merchant ship answering, "I don't know what I would have done."

[32]: 46 An act in 1700 allowed for the expansion of the definition of piracy to include not just those "who committed robbery by sea," but also the "mutineer who ran away with the ship" as well as the "sailor who interfered with the defense of his vessel" under a pirate siege.

Eventually the governments of the known world made villains of these sea raiders, calling them "blood lusting monsters," whose sole purpose was "destroying the social order.

New troubles arose when Silver Screen Entertainment directors, Tom Bernstein and Roland Betts proposed the concept for developing a large-scale museum complex devoted to the Whydah.

Modern scholars have posited many reasons for the rise in piracy in the early eighteenth century, from a growing social emphasis on economics and capitalism[33] to rebellion against an oppressive upper class.