Pittsburgh railroad strike of 1877

Between July 21 and 22 in Pittsburgh, a major center of the Pennsylvania Railroad, some 40 people (including women and children) were killed in the ensuing riots; strikers burned the Union Depot and 38 other buildings at the yards.

Commentators would later place blame for the incident on a range of actors, from the railroad, to reluctant or even sympathetic members of the police and militia, to tramps and vagrants who travelled to the city to take part of the growing public unrest.

Violence began in Martinsburg, West Virginia and spread along the rail lines through Baltimore, and on to several major cities and transportation hubs of the time, including Reading, Scranton and Shamokin, Pennsylvania; a bloodless general strike in St. Louis, Missouri; and a short lived uprising in Chicago, Illinois.

What began as the peaceful actions of organized labor attracted the masses of working discontent and unemployed of the depression, along with others who took opportunistic advantage of the chaos.

[11]: 19 Yet a third group attempted to take the train but were attacked by the strikers, who moved to the stock yards at East Liberty Street, and convinced the men there to join.

He ordered one man to take control of a switch so that the train could be set on the correct track, and when he refused out of fear for his safety, Watt attempted to do so himself and was struck by one of the strikers, who was arrested over the protests of the crowd.

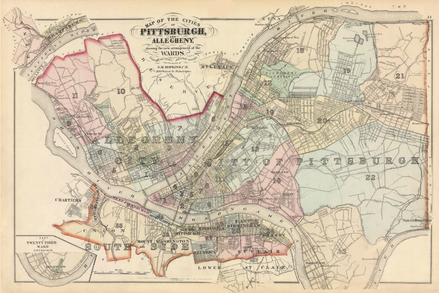

[8]: 79 By midnight, up to 1,400 strikers had gathered in the Pennsylvania Railroad rail yards, which were located on the flats southeast of the Allegheny River, stopping the movement of some 1,500 cars.

[11]: 19 The lieutenant governor, through General Albert Pearson, ordered the 6th Division 18th Regiment of the Pennsylvania National Guard from Philadelphia, to assemble to support the sheriff.

According to the later testimony of a railroad official, Pearson commented that he believed he could have retaken the station with these available forces, but that it would have resulted in a great loss of life, and he was therefore reluctant to do so.

[10]: 8 At 3:30 pm the order was given for the sheriff and his deputies, accompanied by National Guard troops, to move on the outer depot of the Pennsylvania Railroad, where a large mob had gathered, and arrest the group's leaders.

[18] "The sight presented after the soldiers ceased firing was sickening," reported the New York Herald; the area "was actually dotted with the dead and dying.

Within two hours the mob was moving about the city, sacking shops and breaking into armories and a local gun factory to procure arms.

[22]The rioters fell upon the rail yards, set fire to train cars and locomotives, and prevented any effort at extinguishing them, in some cases at gunpoint.

[8]: 101 US Commissioner of Labor Carroll D. Wright would later testify that riots were, in some instances, aided by agents of the railroad company, attempting to destroy aging and soon-to-be replaced cars that they could then charge to the County.

[11]: 23 With the military having retreated, and the large portions of the militia having sided with the rioters, there was little that could be done: "Mayor McCarthy endeavored early in the day to stop the pillage, but the handful of men at his command were unable to control the crowd.

[8]: 105–06 The fire department of the city remained on duty throughout the conflagration, and concentrated their efforts on private property along Liberty Street, as they were continuously prevented by the mob from accessing the burning railroad facilities.

[8]: 107–8 The disturbance spread north across the river, in the town of Allegheny, where employees of the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne, and Chicago Railroad voted to strike.

[24]: 184 They asserted that the assembled militias had no authority (the governor being out of state), raided the local armory, and set up patrols and armed guards in rifle pits and trenches.

All freight traffic in the city was brought to a halt, and the strikers took over control of the telegraph and the railroad, and began managing the running of passenger trains.

Many prominent members of the town had set to work organizing a militia, and by this time several thousand had been gathered and were put under the command of General James S. Negley, a veteran of the Civil War.

[8]: 115–6 [h] On July 28, Governor Hartranft arrived in Pittsburgh with fresh militiamen from Philadelphia, in addition to 14 artillery and 2 infantry companies of federal troops.

[10] In total, authorities were forced to mobilize 3,000 federal troops, and thousands more in state national guard and local militia to Pittsburgh in order to restore and enforce the peace.

"[27]: 63 As Lloyd points out, the railroad may not have taken the possibility of strikes or violence seriously, and chose to announce the change to double headers with full knowledge of outbreaks already happening elsewhere around the country.

[10]: 18 For its part, the final report of the Legislative committee placed blame on both labor and capital, but drew a distinction in stages of events as they unfolded.

They maintained that the strike, as such, was not an insurrection, and blamed the ensuing riots on "tramps and idle vagrants instead of the railroad workers or the unemployed in general.

Their editor, writing that September, asserted: We frankly own that the scenes at Pittsburgh and Chicago were worthy only of the savages who in earlier years roasted and otherwise tortured the Roman priests in Canada.

[29]As French points out, the strike and ensuing riots of 1877 greatly strengthened the cause of organized labor, which had struggled for years, and especially through the depression of the 1870s, to form coherent and effective political and social institutions.

He quoted a leader of the Pittsburgh Knights of Labor as saying that the result of the riots was to "solidify and organize the working men," and French continues to clarify, "especially for political action".

"[28]: 8 In addition, large numbers of men who had become unemployed during the depression were camped near the outskirts of the city, making for what Lloyd dubbed "a volatile mix of poverty and anger".

"[20]: 131 On September 23, 1997, a historical marker was placed at the corner of 28th Street and Liberty in Pittsburgh, commemorating the location of the July 21, 1877 shootings in connection with the strike and ensuing riots.