Planck constant

[3] In 1905, Albert Einstein associated the "quantum" or minimal element of the energy to the electromagnetic wave itself.

[5][6] Planck's constant was formulated as part of Max Planck's successful effort to produce a mathematical expression that accurately predicted the observed spectral distribution of thermal radiation from a closed furnace (black-body radiation).

Approaching this problem, Planck hypothesized that the equations of motion for light describe a set of harmonic oscillators, one for each possible frequency.

He examined how the entropy of the oscillators varied with the temperature of the body, trying to match Wien's law, and was able to derive an approximate mathematical function for the black-body spectrum,[2] which gave a simple empirical formula for long wavelengths.

Applying this new approach to Wien's displacement law showed that the "energy element" must be proportional to the frequency of the oscillator, the first version of what is now sometimes termed the "Planck–Einstein relation":

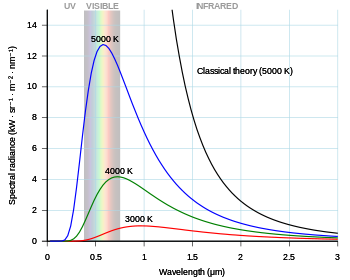

[14] The black-body problem was revisited in 1905, when Lord Rayleigh and James Jeans (together) and Albert Einstein independently proved that classical electromagnetism could never account for the observed spectrum.

These proofs are commonly known as the "ultraviolet catastrophe", a name coined by Paul Ehrenfest in 1911.

They contributed greatly (along with Einstein's work on the photoelectric effect) in convincing physicists that Planck's postulate of quantized energy levels was more than a mere mathematical formalism.

[15] The photoelectric effect is the emission of electrons (called "photoelectrons") from a surface when light is shone on it.

It was first observed by Alexandre Edmond Becquerel in 1839, although credit is usually reserved for Heinrich Hertz,[16] who published the first thorough investigation in 1887.

[17] Einstein's 1905 paper[18] discussing the effect in terms of light quanta would earn him the Nobel Prize in 1921,[16] after his predictions had been confirmed by the experimental work of Robert Andrews Millikan.

[19] The Nobel committee awarded the prize for his work on the photo-electric effect, rather than relativity, both because of a bias against purely theoretical physics not grounded in discovery or experiment, and dissent amongst its members as to the actual proof that relativity was real.

However, the energy account of the photoelectric effect did not seem to agree with the wave description of light.

The "photoelectrons" emitted as a result of the photoelectric effect have a certain kinetic energy, which can be measured.

This kinetic energy (for each photoelectron) is independent of the intensity of the light,[17] but depends linearly on the frequency;[19] and if the frequency is too low (corresponding to a photon energy that is less than the work function of the material), no photoelectrons are emitted at all, unless a plurality of photons, whose energetic sum is greater than the energy of the photoelectrons, acts virtually simultaneously (multiphoton effect).

[22][23] Assuming the frequency is high enough to cause the photoelectric effect, a rise in intensity of the light source causes more photoelectrons to be emitted with the same kinetic energy, rather than the same number of photoelectrons to be emitted with higher kinetic energy.

Einstein's postulate was later proven experimentally: the constant of proportionality between the frequency of incident light

In discussing angular momentum of the electrons in his model Bohr introduced the quantity

[29] The Planck constant also occurs in statements of Werner Heisenberg's uncertainty principle.

There are several other such pairs of physically measurable conjugate variables which obey a similar rule.

In addition to some assumptions underlying the interpretation of certain values in the quantum mechanical formulation, one of the fundamental cornerstones to the entire theory lies in the commutator relationship between the position operator

This energy is extremely small in terms of ordinarily perceived everyday objects.

[30] Eventually, following upon Planck's discovery, it was speculated that physical action could not take on an arbitrary value, but instead was restricted to integer multiples of a very small quantity, the "[elementary] quantum of action", now called the Planck constant.

[31] This was a significant conceptual part of the so-called "old quantum theory" developed by physicists including Bohr, Sommerfeld, and Ishiwara, in which particle trajectories exist but are hidden, but quantum laws constrain them based on their action.

This view has been replaced by fully modern quantum theory, in which definite trajectories of motion do not even exist; rather, the particle is represented by a wavefunction spread out in space and in time.

[34] This value is used to define the SI unit of mass, the kilogram: "the kilogram [...] is defined by taking the fixed numerical value of h to be 6.62607015×10−34 when expressed in the unit J⋅s, which is equal to kg⋅m2⋅s−1, where the metre and the second are defined in terms of speed of light c and duration of hyperfine transition of the ground state of an unperturbed caesium-133 atom ΔνCs.

When the product of energy and time for a physical event approaches the Planck constant, quantum effects dominate.

[36] Equivalently, the order of the Planck constant reflects the fact that everyday objects and systems are made of a large number of microscopic particles.

For example, in green light (with a wavelength of 555 nanometres or a frequency of 540 THz) each photon has an energy E = hf = 3.58×10−19 J.

[38] Many equations in quantum physics are customarily written using the reduced Planck constant, [39]: 104 equal to