Planned French invasion of Britain (1759)

France was prepared to ally with her historic enemy because this would, the Conseil du Roi thought, allow her to concentrate her efforts against Great Britain in a future war.

In reaction, Prussia, which had emerged from the war as a newly significant European power, allied with her previous enemy, Great Britain.

France supported Austria and Russia in a land campaign against Prussia, and launched what she saw as her main effort in a maritime and colonial offensive against Great Britain.

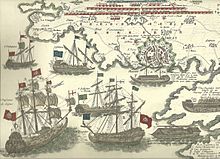

His conception was relatively simple: a massive fleet of flat-bottomed transport craft would carry an army of 100,000 troops across the Channel where they would be landed on the coast of southern England.

Once they landed, they believed they would easily overpower the small army Britain retained on home soil and end the war.

Eventually the French decided to try to recruit Jacobite supporters without involving Charles directly in the operation – as he was considered a potential liability.

A few proposals were made, such as stationing troops on the Isle of Wight, but the consensus was that existing strategy was already sufficient to deal with the invasion threat.

The British shared conventional wisdom that any invasion would have to involve the Brest fleet, but kept a close watch on all potential departure points.

Hundreds of the flat-bottomed transport craft were constructed in Le Havre, Brest, St Malo, Nantes, Morlaix and Lorient.

In spite of opposition from within the French cabinet (particularly the war minister Belle-Isle), Choiseul insisted on launching the crossing without fleet support.

The French decided to launch the invasion force entirely from Le Havre, a large harbour some distance from the blockading British fleet at Brest.

In June, French planners agreed that a separate, smaller force would be sent to Scotland to try to gain Jacobite support, and crush British resistance in a pincer movement.

Plans called for Soubise's force to wait for good winds, and then cross the Channel speedily from Le Havre, landing in Portsmouth.

[19] However, the success of the venture lured the British commanders into a false sense of security, making them believe it had been a greater setback than it had in fact.

A War Council in Paris decided to launch the expedition to Scotland first, and if it was successful, send follow-up forces to Portsmouth and Maldon, Essex.

Delays to the assembly of the invasion force pushed back the date of the launch, and the sea grew rougher and more dangerous to cross.

Conflans declined to leave harbour, as he believed his fleet was not ready, and on 20 October the British returned to blockade the French Atlantic ports again.

Their intended destination had been the West Indies, but the loss of ships and men stretched the French fleet almost to breaking point, and raised questions about the viability of the invasion.

The invasion plan received a crippling blow in November, when the French Brest Squadron was heavily defeated at the Battle of Quiberon Bay.

Conflans had sailed from Brest on 15 November heading a hundred miles down the coast to Quiberon Bay, where the invasion army was now waiting to board his transports.

Conflans' fleet became caught in a storm which slowed them down and allowed the pursuing British under Sir Edward Hawke a chance to catch up with them.

Conflans initially formed a line of battle and prepared to engage, but then changed his mind and his ships raced to take shelter in the bay.

Hawke pursued, taking a high risk in the middle of a violent storm, and captured or drove ashore five French ships.

Choiseul continued to advocate a direct strike against Britain as the way to win future wars, and despatched engineers and agents to examine British defences in preparation.