Plastic recycling

[1][2][3] Recycling can reduce dependence on landfills, conserve resources and protect the environment from plastic pollution and greenhouse gas emissions.

Alternatively, plastic can be burned in place of fossil fuels in energy recovery facilities, or biochemically converted into other useful chemicals for industry.

Plastic recycling is low in the waste hierarchy, meaning that reduction and reuse are more favourable and long-term solutions for sustainability.

It has been advocated since the early 1970s,[15] but due to economic and technical challenges, did not impact the management of plastic waste to any significant extent until the late 1980s.

For example, an April 1973 report written by industry scientists stated that, "There is no recovery from obsolete products" and that, "A degradation of resin properties and performance occurs during the initial fabrication, through aging, and in any reclamation process."

Although better technology was known,[29] these early incinerators often lacked advanced combustors or emission-control systems, leading to the release of dioxins and dioxin-like compounds.

Globalisation during the 1990s included the export of plastic waste from advanced economies to developing and middle-income ones, where it could be sorted and recycled less expensively.

[36][37] Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand reacted to illegal plastic waste imports by reinforcing border controls.

Parties to the convention are required to ensure environmentally sound management of their refuse either through alternative importers or by increasing capacity.

The Commission then issued a strategic document in January 2018 which set out an "ambitious vision" and an opportunity for global action on plastic recycling.

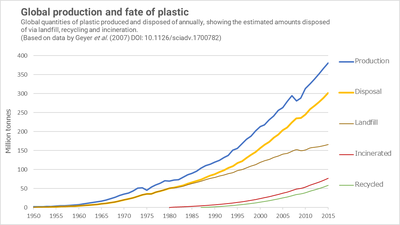

Although the percentage of recycled or incinerated material is increasing each year, the tonnage of waste left-over also continues to rise.

[11] The percentage of plastic that can be fully recycled, rather than downcycled or go to waste, can be increased when manufacturers minimise mixing of packaging materials and eliminate contaminants.

As of 2022 North American countries (NAFTA) accounted for 21% of global plastic consumption, closely followed by China (20%) and Western Europe (18%).

Waste is sent to a materials recovery facility or MBT plant where the plastic is separated, cleaned and sorted for sale.

Although many plastic items have identification codes workers rarely have time to look for them, so leaving problems of inefficiency and inconsistency.

This approach is largely automated and involves various sensors linked to a computer, which analyses items and directs them into appropriate chutes or belts.

[83] Near-infrared spectroscopy can be used to distinguish polymer types,[84] although black/strongly-coloured plastics, as well as composite materials like plastic-coated paper and multilayered packaging, which can give misleading readings.

For instance, oxo-biodegradable additives, intended to improve the biodegradability of plastic, also increase the degree of thermal degradation.

The continual mechanical recycling of plastic without reduction in quality is challenging due to cumulative polymer degradation[97] and risk of contaminant build-up.

Compatibilised plastics can be used as a replacement for virgin material, as it is possible to produce them with the right melt flow index needed for good results.

[107][108][109] In theory, this allows for near infinite recycling; as impurities, additives, dyes and chemical defects are completely removed with each cycle.

Implementation is limited because technologies do not yet exist to reliably depolymerise all polymers on an industrial scale and also because the equipment and operating costs are much higher.

[86] PET, PU and PS are depolymerised commercially to varying extents,[110] but the feedstock recycling of polyolefins, which make-up nearly half of all plastics, is much more limited.

[111] Certain polymers like PTFE, polystyrene, nylon 6, and polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) undergo thermal depolymerisation when heated to sufficiently high temperatures.

[121] It is distinct from incineration without energy recovery, which is historically more common, but which does not reduce either plastic production or fossil fuel use.

Compared to the sometimes variable market for recyclables, demand for electricity is universal and better understood, reducing the perceived financial risk.

In either approach PVC must be excluded or compensated for by installing dechlorination technologies, as it generates large amounts of hydrogen chloride (HCl) when burnt.

[124] Burning has long been associated with the release of harmful dioxins and dioxin-like compounds, however these hazards can be abated by the use of advanced combustors and emission control systems.

Incineration with energy recovery remains the most common method, with more advanced waste-to-fuel technologies such as pyrolysis hindered by technical and cost hurdles.

[136] Life-cycle analysis shows that plastic-to-fuel can displace fossil fuels and lower net greenhouse gas emissions (~15% reduction).

- Blue is widely recycled

- Yellow is sometimes recycled

- Red is usually not recycled