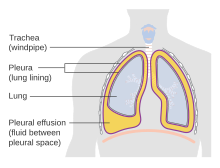

Pleural cavity

The parietal pleura is attached to the mediastinum, the upper surface of the diaphragm, and to the inside of the ribcage.

[1] In humans, the left and right lungs are completely separated by the mediastinum, and there is no communication between their pleural cavities.

The visceral pleura receives its blood supply from the parenchymal capillaries of the underlying lung, which have input from both the pulmonary and the bronchial circulation.

The parietal pleura receives its blood supply from whatever structures underlying it, which can be branched from the aorta (intercostal, superior phrenic, and inferior phrenic arteries), the internal thoracic (pericardiacophrenic, anterior intercostal, and musculophrenic branches), or their anastomosis.

The two cavities communicate via a slim pair of remnant coeloms adjacent to the upper foregut called the pericardioperitoneal canal.

Most fluid is produced by the exudation in parietal circulation (intercostal arteries) via bulk flow and reabsorbed by the lymphatic system.

The capillary equilibrium model states that the high negative apical pleural pressure leads to a basal-to-apical gradient at the mediastinal pleural surface, leading to a fluid flow directed up toward the apex (helped by the beating heart and ventilation in lungs).

Finally there is a traverse flow from margins to flat portion of ribs completes the fluid circulation.

Transudative pleural effusions occur in congestive heart failure (CHF), cirrhosis, or nephrotic syndrome.

Localized pleural fluid effusion noted during pulmonary embolism (PE) results probably from increased capillary permeability due to cytokine or inflammatory mediator release from the platelet-rich thrombi.

[11] When accumulation of pleural fluid is noted, cytopathologic evaluation of the fluid, as well as clinical microscopy, microbiology, chemical studies, tumor markers, pH determination and other more esoteric tests are required as diagnostic tools for determining the causes of this abnormal accumulation.

The presence of heart failure, infection, or malignancy within the pleural cavity are the most common causes that can be identified using this approach.

In spite of the lack of knowledge of the cause of the effusion, treatment may be required to relieve the most common symptom, dyspnea, as this can be quite disabling.

Thoracoscopy has become the mainstay of invasive procedures as closed pleural biopsy has fallen into disuse.