Pliny the Younger on Christians

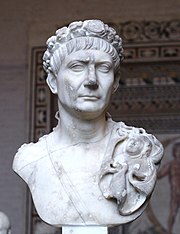

Pliny the Younger, the Roman governor of Bithynia and Pontus (now in modern Turkey), wrote a letter to Emperor Trajan around AD 110 and asked for counsel on dealing with the early Christian community.

The letter (Epistulae X.96) details an account of how Pliny conducted trials of suspected Christians who appeared before him as a result of anonymous accusations and asks for the Emperor's guidance on how they should be treated.

[11] Trajan's reply also offers valuable insight into the relationship between Roman provincial governors and Emperors and indicates that at the time Christians were not sought out or tracked down by imperial orders, and that persecutions could be local and sporadic.

[12] Pliny the Younger was the governor of Bithynia and Pontus on the Black Sea coast of Anatolia, having arrived there as the representative of Emperor Trajan between 109 and 111 AD on September 17.

[1] Given the reference to Bithynia in the opening of the First Epistle of Peter (most likely written during the reign of Domitian in AD 81), Christianity in the region may have had some Petrine associations through Silas.

[3] However Eusebius (E.H. 9.7) asserts that it was fear of the gods being displeased by the Christians' refusal to worship them causing disasters to fall on cities that led to persecution.

[15] He has three main questions: A. N. Sherwin-White states that “When the practice of a sect was banned, indictment of the nomen (“name”), i.e. of membership of a cult group, sufficed to secure conviction.

This looked uncommonly like religious persecution to the victims themselves, but the underlying ground remained the flagitia ("shameful acts") supposed to be inseparable from the practice of the cult.”[16] Pliny gives an account of how the trials are conducted and the various verdicts (sections 4–6).

He says he first asks if the accused is a Christian: if they confess that they are, he interrogates them twice more, for a total of three times, threatening them with death if they continue to confirm their beliefs.

Despite his uncertainty about the offences connected with being Christian, Pliny says that he has no doubt that, whatever the nature of their creed, at least their inflexible obstinacy (obstinatio) and stubbornness, (pertinacia) deserve punishment.

This shows that, to the Roman authorities, Christians were being hostile to the government and were openly defying a magistrate who was asking them to abandon an unwanted cult.

Sherwin-White says the procedure was approved by Trajan but it was not a way to "compel conformity to the state religion or imperial cult", which was a voluntary practice.

Pliny then details the practices of Christians (sections 7–10): he says that they meet on a certain day before light where they gather and sing hymns to Christ as to a god.

[21] The apparent abandonment of the pagan temples by Christians was a threat to the pax deorum, the harmony or accord between the divine and humans, and political subversion by new religious groups was feared, which was treated as a potential crime.

[22] Pliny ends the letter by saying that Christianity is endangering people of every age and rank and has spread not only through the cities, but also through the rural villages as well (neque tantum ... sed etiam), but that it will be possible to check it.

[28] Although Emperor Trajan gives Pliny specific advice about disregarding anonymous accusations, for example, he was deliberate in not establishing any new rules in regard to the Christians.