Treaty of Point Elliott

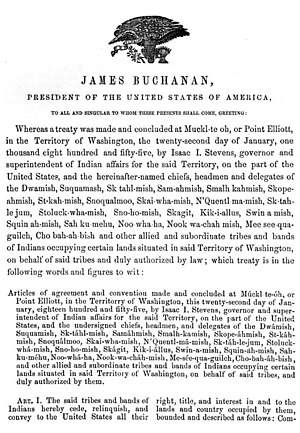

[3] The treaty was signed on January 22, 1855, at Muckl-te-oh or Point Elliott, now Mukilteo, Washington, and ratified 8 March and 11 April 1859.

[4] Signatories to the Treaty of Point Elliott included Chief Seattle (si'áb Si'ahl) and Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens.

Native Americans were disconcerted by the encroachment of the settlers on their territory, and sometimes reacted by making raids or forming uprisings against them.

[6] The courts have said that the power of Congress in Indian affairs is plenary (full and complete)—great but under present law not absolute.

[Deloria, 1994][8] Indian tribes, for the most part, were not parties to and rarely agreed with the diminution in their sovereign powers by the alien tradition of European law.

They have often claimed, in cases since the late twentieth century, to retain greater sovereign powers than federal Indian law is prepared to concede.

Washington Territory Governor Isaac Stevens frequently made oral promises to tribal representatives that were not matched by what his office put in writing.

Stevens approved treaties which Judge James Wickerson would characterize forty years later as "unfair, unjust, ungenerous, and illegal".

The local natives had a 30-year history of dealing with the "King George's men" of Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), who had developed a reputation for driving a hard bargain, but sticking honestly to what they agreed to, and for treating Whites and Indians impartially.

[12] Historian Morgan suggested that Stevens appointed certain chiefs of tribes in order to facilitate goals of his administration.

[13] "The salient features of the policy outlined [by Governor Stevens to his advisers] were as follows: Indian tribes believed the treaties became effective when they were signed by the officials they had dealt with.

[15] European Americans began to settle about 1845 but Congress did not approve the treaty until April 1859, which made such settlement legal.

Samish attendance was documented by ethnologist George Gibbs and officially reported by Governor Issac Stevens.

The President may hereafter, when in his opinion the interests of the Territory shall require and the welfare of the said Indians be promoted, remove them from either or all of the special reservations herein before make to the said general reservation, or such other suitable place within said Territory as he may deem fit, on remunerating them for their improvements and the expenses of such removal, or may consolidate them with other friendly tribes or bands; and he may further at his discretion cause the whole or any portion of the lands hereby reserved, or of such other land as may be selected in lieu thereof, to be surveyed into lots, and assign the same to suc[h] individuals or families as are willing to avail themselves of the privilege, and will locate on the same as a permanent home on the same terms and subject to the same regulations as are provided in the sixth article of the treaty with the Omahas, so far as the same may be applicable.An attorney in the employ of the Natives during negotiations was concerned on their behalf with this language.

The said tribes and bands further agree not to trade at Vancouver's Island or elsewhere out of the dominions of the United States, nor shall foreign Indians be permitted to reside in their reservations without consent of the superintendent or agent.The complete treaty, unabridged can be found on Wikisource.

[19] In 1930, the Point Elliott Treaty Monument was erected by the Marcus Whitman Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution at the northeast corner of Lincoln Avenue and 3rd Street in Mukilteo.

[20] As of 2024, the plaque at the monument reads: 1885 1930 At this place on January 22, 1855, Governor Issac I. Stevens concluded the treaty by which the Indians ceded the lands from Point Pully to the British boundary.