Polaris expedition

Hall possessed the necessary survival skills, but lacked an academic background and had no experience leading men or commanding a ship.

Insubordination loomed, mainly at the instigation of chief scientist Emil Bessels and meteorologist Frederick Meyer—both German—who looked down on what they perceived to be their unqualified commander.

Bessels and Meyer were supported by the German half of the crew, further increasing tensions among a group of men that were already divided by nationality.

On the way southward, nineteen members of the expedition became separated from their ship and drifted on an ice floe for six months and 1,800 miles (2,900 km) before being rescued.

In 1827, Sir Edward Parry led a British Royal Navy expedition with the aim to be the first men to reach the North Pole.

[1] In the next five decades following Parry's attempt, the Americans would mount three such expeditions: Elisha Kent Kane in 1853–1855,[2] Isaac Israel Hayes in 1860–1861,[3] and Charles Francis Hall with the Polaris in 1871–1873.

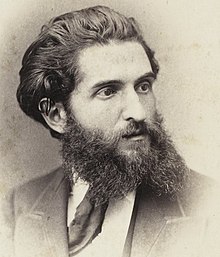

He had previously worked as a blacksmith and as an engraver, and for a couple of years had published his own newspaper, the Cincinnati Occasional (later renamed the Daily Press).

[4] Energetic and enterprising, Hall enthusiastically wrote about the latest technological innovations; he was fascinated by hot air balloon travel and praised the new transatlantic telegraph cable.

[19] In addition to the 25 officers, crew and scientific staff, Hall brought along his native companions whose assistance he had relied on during his earlier expeditions; guide and hunter Ipirvik, interpreter and seamstress Taqulittuq, as well as their infant son.

[20] Later, at Upernavik, also joining their ranks would be Hans Hendrik,[21] the esteemed Greenlandic Inuk hunter previously employed by Kane and Hayes on their respective expeditions, and whose expertise had been crucial to their survival, helping ward off starvation.

"[23] Reluctant to increase their number with "four useless mouths,"[23] Hall acquiesced so that now, besides Hendrik's wife, added to their complement were three young children.

By September 2, Polaris had reached her furthest parallel north, 82° 29′ N.[30] Tension flared again as the three leading officers could not agree on whether to proceed any further.

[34] With Tyson watching over the ship, Hall took two sleds with first mate Chester and the native guides Ipirvik and Hendrik, leaving on October 10.

In his book Trial by Ice, Richard Parry postulated that such a note from the uneducated Hall must have rankled Bessels, who held degrees from universities in Stuttgart, Heidelberg and Jena.

There is no stated time for putting out lights; the men are allowed to do as they please; and, consequently, they often make nights hideous by their carousing, playing cards to all hours.

On January 1, 1872, Tyson wrote in his diary: "Last month such an astonishing proposition was made to me that I have never ceased thinking of it since [...] It grew out of a discussion as to the feasibility of attempting to get farther north next summer.

Now three of the ship's precious lifeboats were lost, and a fourth, the small scow, would be crushed by ice in July after being carelessly left out overnight.

"[54] Exasperated by his companions' apathy and very much aware that they might never again find themselves presented with an opportunity as good as the one they were currently facing, Tyson added: "Some one will some day reach the pole, and I envy not those who have prevented Polaris having that chance.

When morning came, the group, consisting of Tyson, Meyer, six of the seamen, the cook, the steward and all of the Inuit, found themselves stranded on an ice floe.

[56] The castaways could see Polaris eight to ten miles (13 to 16 km) away, but attempts to attract the ship's attention with a large black cloth were futile.

[57] The group drifted over 1,800 miles (2,900 km) on the ice floe for the next six months[59] before being rescued off the coast of Newfoundland by the whaler Tigress on April 30, 1873.

Having lost much of their bedding, clothing and food when it was haphazardly jettisoned from the ship on October 12, the remaining fourteen men were in poor condition to face another winter.

The board consisted of Robeson, Admiral Louis M. Goldsborough, Commodore William Reynolds, Army Captain Henry W. Howgate and Spencer Fullerton Baird of the Academy of Sciences.

[73] Faced with conflicting testimony, lack of official records and journals, and no body for an autopsy, no charges were laid in connection with Hall's death.

Tyson was perplexed as to why the ship could not see them eight miles (13 km) distant, a group of men and supplies waving a dark-colored flag in a sea of white.

In defense of Budington's decision, when low tide exposed the ship's hull, the men found that the stem had broken completely away at the six-foot mark, taking iron sheeting and planking with it.

[80] Indeed, the pains that Hall complained about down one side of his body, which he attributed to many years' huddling in an igloo, may have been due to a previous minor stroke.

Tests on tissue samples of bone, fingernails and hair showed that he had received large doses of arsenic in the last two weeks of his life.

[83] Acute arsenic poisoning appears consistent with the symptoms party members reported: stomach pains, vomiting, dehydration, stupor and mania.

[85] In The Arctic Grail, Pierre Berton suggests that it is possible that Hall accidentally dosed himself with the poison, as arsenic was common in medical kits of the time.