Policy

Moreover, governments and other institutions have policies in the form of laws, regulations, procedures, administrative actions, incentives and voluntary practices.

Policies can be understood as political, managerial, financial, and administrative mechanisms arranged to reach explicit goals.

Third, the individual or organization can provide a sound account for this support by explaining the evidence and preferences that lay the foundation for the claim.

Broadly, policies are typically instituted to avoid some negative effect that has been noticed in the organization, or to seek some positive benefit.

[citation needed] A meta-analysis of policy studies concluded that international treaties that aim to foster global cooperation have mostly failed to produce their intended effects in addressing global challenges, and sometimes may have led to unintended harmful or net negative effects.

The study suggests enforcement mechanisms are the "only modifiable treaty design choice" with the potential to improve the effectiveness.

In recent years, the numbers of hybrid cars in California has increased dramatically, in part because of policy changes in Federal law that provided USD $1,500 in tax credits (since phased out) and enabled the use of high-occupancy vehicle lanes to drivers of hybrid vehicles.

In this case, the organization (state or federal government) created an effect (increased ownership and use of hybrid vehicles) through policy (tax breaks, highway lanes).

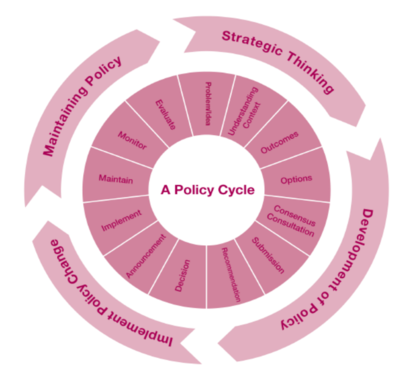

[15] Due to these problems, alternative and newer versions of the model have aimed to create a more comprehensive view of the policy cycle.

[4] Distributive policies involve government allocation of resources, services, or benefits to specific groups or individuals in society.

These policies are intended to address issues related to public safety, consumer protection, and environmental conservation.

[4] Constituent policies are less concerned with the allocation of resources or regulation of behavior, and more focused on representing the preferences and values of the public.

[4] Redistributive policies involve the transfer of resources or benefits from one group to another, typically from the wealthy or privileged to the less advantaged.

Progressive taxation, welfare programs, and financial assistance to low-income households are examples of redistributive policies.

In contemporary systems of market-oriented economics and of homogeneous voting of delegates and decisions, policy mixes are usually introduced depending on factors that include popularity in the public (influenced via media and education as well as by cultural identity), contemporary economics (such as what is beneficial or a burden in the long- and near-term within it) and a general state of international competition (often the focus of geopolitics).

Broadly, considerations include political competition with other parties and social stability as well as national interests within the framework of global dynamics.

[17][additional citation(s) needed] Policies or policy-elements can be designed and proposed by a multitude of actors or collaborating actor-networks in various ways.

[19][20][21][22][additional citation(s) needed] Contemporary ways of policy-making or decision-making may depend on exogenously-driven shocks that "undermine institutionally entrenched policy equilibria" and may not always be functional in terms of sufficiently preventing and solving problems, especially when unpopular policies, regulation of influential entities with vested interests,[22] international coordination and non-reactive strategic long-term thinking and management are needed.

In the modern highly interconnected world, polycentric governance has become ever more important – such "requires a complex combination of multiple levels and diverse types of organizations drawn from the public, private, and voluntary sectors that have overlapping realms of responsibility and functional capacities".

A review about worldwide pollution as a major cause of death – where it found little progress, suggests that successful control of conjoined threats such as pollution, climate change, and biodiversity loss requires a global, "formal science–policy interface", e.g. to "inform intervention, influence research, and guide funding".