Polish–Lithuanian War

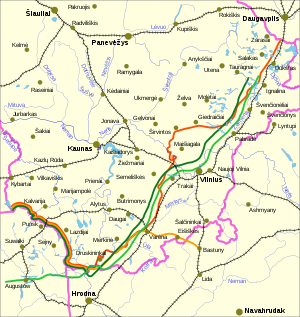

After World War I, the military and political situation in the region was chaotic, as multiple countries, notably Lithuania, Poland, and Soviet Russia, vied with each other over control of overlapping areas.

[22] Lithuania remained adamant regarding its claim to Vilnius as its constitutional capital throughout the whole interwar,[21] and breaking all diplomatic relations with Poland due to the latter's control of the city.

At the end of 1918, four groups claiming authority existed in Vilnius: the occupational Ober Ost German government, which was preparing to leave the city; the Lithuanian government under Augustinas Voldemaras that had just begun creating the Lithuanian Army; the Polish Committee and the Polish Temporary National Council for Lithuania supported by armed units of the Self-Defence of Lithuania and Belarus; and Vilnius Soviet of Workers Deputies waiting for the Red Army.

[6] Polish–Lithuanian relations at the time were not immediately hostile, both armies met in several points (Merkinė, Vievis and Širvintos), and even cooperated against the Bolsheviks in Giedraičiai area on May 11, 1919.

[10] Though there was no formal state of war and few casualties, by July newspapers reported increasing clashes between Poles and Lithuanians, primarily around the towns of Merkinė and Širvintos.

[57] However, Alfred E. Senn wrote that the issue of the border and the belonging of Vilnius was not addressed in the treaty,[55] while according to Pranas Čepėnas and Wiktor Sukiennicki [pl] the signed agreement mentioned nothing regarding territorial questions.

[58] After the Germans had withdrawn, the Lithuanian side pressed for Poland's recognition of an independent Lithuania with its capital in Vilnius, which the Polish leadership consistently rejected.

[59] Polish leader Józef Piłsudski hoped to revive the old Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (see the Intermarium federation) and campaigned for some kind of Polish–Lithuanian union in the Paris Peace Conference.

[61] Poland also did not intend to make any territorial concessions and justified its actions not only as part of a military campaign against the Soviets but also as the right of self-determination of local Poles.

[68] The Lithuanian delegation was also present at the Paris Peace Conference, where its leader Augustinas Voldemaras focused on receiving recognition of independent Lithuania and its borders.

[81] Two major modifications favorable to the Poles were made: the Suwałki Region was assigned to Poland and the entire line was moved about 7 km (4.3 mi) west.

[87] The Sejny branch of Polish Military Organisation (PMO) began preparing for an uprising, scheduled for the night of August 22 to 23, 1919, right after German troops left the city.

[80] Sometime in mid-July 1919,[90] PMO forces in Vilnius began planning a coup to replace the Lithuanian government with a pro-Polish cabinet, which would agree to a union with Poland (the proposed Międzymorze federation).

[80] On August 3, a Polish diplomatic mission, led by Leon Wasilewski and Tadeusz Kasprzycki, in Kaunas had a double purpose: propose a plebiscite in the contested territories[91] and assess preparedness for the coup.

[91] According to Lithuanian historian Kazys Ališauskas, PMO planned to capture and hold Kaunas for a few hours until the arrival of the regular Polish troops, situated only some 40–50 km (25–31 mi) east from the city.

They were bolstered in this conviction by intra-Lithuanian quarrels, primarily between Lithuanian émigré leader Juozas Gabrys and newly elected President Smetona, who lacked democratic legitimacy.

[99] The postponement of the start of the coup turned out to be a fatal mistake, as some PMO units did not receive information about it and began operations on the original date, disrupting telegraph connections between Kaunas and the rest of the country.

[114] Wasilewski then began propaganda work involving Lithuanian activists Józef Albin Herbaczewski, priest Antanas Viskantas or Jurgis Aukštuolaitis, who had been released from prison, and published bilingual or Lithuanian-language press for this purpose.

[119] In April 1920, Lithuania held its first parliamentary elections, among the constituencies established were cities outside the Lithuanian administration: Vilnius, Lida, Grodno and Białystok.

On July 9, Polish Prime Minister Władysław Grabski asked the Allied Powers in the Spa Conference for military assistance in the war with the Soviets.

[62] Grabski opposed the transfer of Vilnius, but under the pressure of British Prime Minister Lloyd George, agreed to the resolution on July 10.

[127] On August 6, after long and heated negotiations, Lithuania and Soviet Russia signed a convention regarding the withdrawal of Russian troops from the recognized Lithuanian territory.

[152] On September 8, during a planning meeting of the Battle of the Niemen River, the Poles decided to manoeuvre through the Lithuanian-held territory to the rear of the Soviet Army, stationed in Grodno.

[154] On September 5, 1920, Polish Foreign Minister Eustachy Sapieha delivered a diplomatic note to the League of Nations alleging that Lithuania violated its neutrality and asked to intervene in the Polish–Lithuanian War.

[177] Polish chief of state Józef Piłsudski ordered his subordinate, General Lucjan Żeligowski, to stage a mutiny with his 1st Lithuanian–Belarusian Division (16 battalions with 14,000 soldiers)[178] in Lida and capture Vilnius in fait accompli.

[196] However, the Lithuanians trusted the League of Nations would resolve the dispute in their favour[179] and were afraid that in case of an attack on Vilnius regular Polish forces would arrive to reinforce Żeligowski's units.

[211] The League of Nations then moved on from trying to solve the narrow territorial dispute in the Vilnius Region to shaping the fundamental relationship between Poland and Lithuania.

[215] The League accepted the status quo in February 1923 by dividing the neutral zone and setting a demarcation line, which was recognised in March 1923 as the official Polish–Lithuanian border.

[215] Some historians, notably Alfred E. Senn, have asserted that if Poland had not prevailed in the Polish–Soviet War, Lithuania would have been invaded by the Soviets and would never have experienced two decades of independence.

[217] For example, Lithuania broke off diplomatic relations with the Holy See after the Concordat of 1925 established an ecclesiastical province in Wilno and thereby acknowledged Poland's claims to the city.