Polish Corridor

[21] Karl Andree, in Polen: in geographischer, geschichtlicher und culturhistorischer Hinsicht (Leipzig 1831), gives the total population of West Prussia as 700,000 – including 50% Poles (350,000), 47% Germans (330,000) and 3% Jews (20,000).

[22] Data from the 19th century and early 20th century show the following ethnic changes in four main counties of the corridor (Puck and Wejherowo on the Baltic Sea coast; Kartuzy and Kościerzyna between the Province of Pomerania and Free City of Danzig): During the First World War, both sides made bids for Polish support, and in turn Polish leaders were active in soliciting support from both sides.

Roman Dmowski, a former deputy in the Russian State Duma and the leader of the Endecja movement was especially active in seeking support from the Allies.

Giving Poland access to the sea was one of the guarantees proposed by United States President Woodrow Wilson in his Fourteen Points of January 1918.

[34] As the Polish commission report to the Allied Supreme Council noted on 12 March 1919: "Finally the fact must be recognized that 600,000 Poles in West Prussia would under any alternative plan remain under German rule".

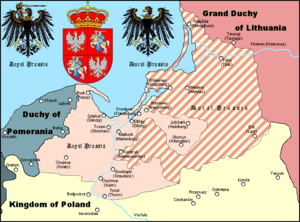

"[59]By 1938, 77.7% of Polish exports left either through Gdańsk (31.6%) or the newly built port of Gdynia (46.1%)[60] David Hunter Miller, in his diary from the Paris Peace Conference, noted that the problem of Polish access to the sea was very difficult because leaving the entirety of Pomerelia under German control meant cutting off millions of Poles from their commercial outlet and leaving several hundred thousand Poles under German rule, while granting such access meant cutting off East Prussia from the rest of Germany.

During World War I, the Central Powers had forced the Imperial Russian troops out of Congress Poland and Galicia, as manifested in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on 3 March 1918.

Following the military defeat of Austria-Hungary, an independent Polish republic was declared in western Galicia on 3 November 1918, the same day Austria signed the armistice.

The collapse of Imperial Germany's Western Front, and the subsequent withdrawal of her remaining occupation forces after the Armistice of Compiègne on 11 November allowed the republic led by Roman Dmowski and Józef Piłsudski to seize control over the former Congress Polish areas.

Starting in December, the Polish-Ukrainian War expanded the Polish republic's territory to include Volhynia and parts of eastern Galicia, while at the same time the German Province of Posen (where even according to the German made 1910 census 61.5% of the population was Polish) was severed by the Greater Poland uprising, which succeeded in attaching most of the province's territory to Poland by January 1919.

The call was answered by the minister of defence Gustav Noske, who decreed support for raising and deploying volunteer Grenzschutz [de] forces to secure East Prussia, Silesia and the Netze District.

[67] After the dock workers of Danzig harbour went on strike during the Polish–Soviet War, refusing to unload ammunition,[68] the Polish Government decided to build an ammunition depot at Westerplatte, and a seaport at Gdynia in the territory of the Corridor, connected to the Upper Silesian industrial centers by the newly constructed Polish Coal Trunk Line railways.

The Prussian Settlement Commission established a further 154,000 colonists, including locals, in the provinces of Posen and West Prussia before World War I.

[77] German political scientist Stefan Wolff, Professor at the University of Birmingham, claims that the actions of Polish state officials after the corridor's establishment followed "a course of assimilation and oppression".

[79] Polish author Władysław Kulski says that a number of them were civil servants with no roots in the province and around 378,000,[clarification needed] and this is to a lesser degree is confirmed by some German sources such as Hermann Rauschning.

[80] Christian Raitz von Frentz notes "that many of the repressive measures were taken by local and regional Polish authorities in defiance of Acts of Parliament and government decrees, which more often than not conformed with the minorities treaty, the Geneva Convention and their interpretation by the League council – though it is also true that some of the central authorities tacitly tolerated local initiatives against the German population.

"[69] While there were demonstrations and protests and occasional violence against Germans, they were at a local level, and officials were quick to point out that they were a backlash against former discrimination against Poles.

[80] Helmut Lippelt writes that Germany used the existence of the German minority in Poland for political ends and as part of its revisionist demands, which resulted in Polish countermeasures.

[84] In the period leading up to the East Prussian plebiscite in July 1920, the Polish authorities tried to prevent traffic through the Corridor, interrupting postal, telegraphic and telephone communication.

[96] On 24 October 1938, the German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop asked the Polish ambassador Józef Lipski to have Poland sign the Anti-Comintern Pact.

[99] Following negotiations with Hitler on the Munich Agreement, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain reported that, "He told me privately, and last night he repeated publicly, that after this Sudeten German question is settled, that is the end of Germany's territorial claims in Europe".

[101] In November 1938, Danzig's district administrator, Albert Forster, reported to the League of Nations that Hitler had told him Polish frontiers would be guaranteed if the Poles were "reasonable like the Czechs."

[103] Initially, the main concern of German diplomacy was not Danzig or the Polish Corridor, but rather having Poland sign the Anti-Comintern Pact, which as the American historian Gerhard Weinberg noted was "... a formal gesture of political and diplomatic obeisance to Berlin, separating them from any other past or prospective international ties, and having nothing to do with the Soviet Union at all".

[103] In late 1938–early 1939, Hitler had decided upon war with Britain and France, and having Poland sign the Anti-Comintern Pact was intended to protect Germany's eastern border while the Wehrmacht turned west.

[103] In November 1938, Hitler ordered his Foreign Minister Ribbentrop to convert the Anti-Comintern Pact, which had been signed with the Empire of Japan in 1936 and joined by Fascist Italy in 1937 into an anti-British military alliance.

[101] Hitler's credibility outside Germany was very low after the occupation of Czechoslovakia, though some British and French politicians approved of a peaceful revision of the corridor's borders.

[109] In 1939, Nazi Germany made another attempt to renegotiate the status of Danzig;[102][110][111] Poland was to retain a permanent right to use the seaport if the route through the Polish Corridor was to be constructed.

Nevertheless, at midnight on August 29, von Ribbentrop handed British Ambassador Sir Nevile Henderson a list of terms that would allegedly ensure peace in regard to Poland.

[124] At the 1945 Potsdam Conference following the German defeat in World War II, Poland's borders were reorganized at the insistence of the Soviet Union, which occupied the entire area.

He depicted the war as beginning in January 1940 and would involve heavy aerial bombing of civilians, but that it would result in a 10-year trench warfare-esque stalemate between Poland and Germany eventually leading to a worldwide societal collapse in the 1950s.