Polish culture during World War II

Despite severe retribution by the Nazis and Soviets, Polish underground cultural activities, including publications, concerts, live theater, education, and academic research, continued throughout the war.

[7] Much of the German policy on Polish culture was formulated during a meeting between the governor of the General Government, Hans Frank, and Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels, at Łódź on 31 October 1939.

[7][10] He and Frank agreed that opportunities for the Poles to experience their culture should be severely restricted: no theaters, cinemas or cabarets; no access to radio or press; and no education.

[7][10] Spectacles of "low quality", including those of an erotic or pornographic nature, were however an exception—those were to be popularized to appease the population and to show the world the "real" Polish culture as well as to create the impression that Germany was not preventing Poles from expressing themselves.

"[19] This divisive policy was reflected in the Germans' decision to destroy Polish education, while at the same time, showing relative tolerance toward the Ukrainian school system.

[23] Notable items plundered by the Nazis included the Altar of Veit Stoss and paintings by Raphael, Rembrandt, Leonardo da Vinci, Canaletto and Bacciarelli.

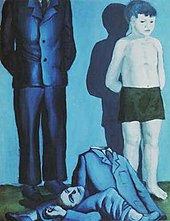

[29] Many university professors, as well as teachers, lawyers, artists, writers, priests and other members of the Polish intelligentsia were arrested and executed, or transported to concentration camps, during operations such as AB-Aktion.

"[22] As part of their program to suppress Polish culture, the German Nazis attempted to destroy Christianity in Poland, with a particular emphasis on the Roman Catholic Church.

Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler wrote, in a memorandum of May 1940: "The sole purpose of this schooling is to teach them simple arithmetic, nothing above the number 500; how to write one's name; and the doctrine that it is divine law to obey the Germans ....

[9][39][42] By late 1940, no official Polish educational institutions more advanced than a vocational school remained in operation, and they offered nothing beyond the elementary trade and technical training required for the Nazi economy.

[22][48] In 1940, several German-controlled printing houses began operating in occupied Poland, publishing items such as Polish-German dictionaries and antisemitic and anticommunist novels.

[10] Visual artists, including painters and sculptors, were compelled to register with the German government; but their work was generally tolerated by the underground unless it conveyed propagandist themes.

"[2] In September 1939, many Polish Jews had fled east; after some months of living under Soviet rule, some of them wanted to return to the German zone of occupied Poland.

[73] He reversed his decision again, however, when a need arose for Polish-language pro-Soviet propaganda following the German invasion of the Soviet Union; as a result, Stalin permitted the creation of Polish forces in the East and later decided to create a Communist People's Republic of Poland.

[78] These Departments oversaw efforts to save from looting and destruction works of art in state and private collections (most notably, the giant paintings by Jan Matejko that were concealed throughout the war).

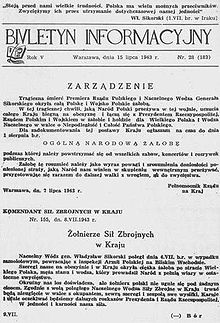

[49] Thus, they sponsored the underground publication (bibuła) of works by Winston Churchill and Arkady Fiedler and of 10,000 copies of a Polish primary-school primer and commissioned artists to create resistance artwork (which was then disseminated by Operation N and like activities).

[78] In response to the German closure and censorship of Polish schools, resistance among teachers led almost immediately to the creation of large-scale underground educational activities.

[9][83][84] More than 90,000 secondary-school pupils attended underground classes held by nearly 6,000 teachers between 1943 and 1944 in four districts of the General Government (centered on the cities of Warsaw, Kraków, Radom and Lublin).

The Germans had almost certainly realized the full scale of the Polish underground education system by about 1943 but lacked the manpower to put an end to it, probably prioritizing resources to dealing with the armed resistance.

[95][96] In 1943 a German report on education admitted that control of what was being taught in schools, particularly rural ones, was difficult, due to lack of manpower, transportation, and the activities of the Polish resistance.

[106] Writers wrote about the difficult conditions in the prisoner-of-war camps (Konstanty Ildefons Gałczyński, Stefan Flukowski, Leon Kruczkowski, Andrzej Nowicki and Marian Piechała), the ghettos, and even from inside the concentration camps (Jan Maria Gisges, Halina Gołczowa, Zofia Górska (Romanowiczowa), Tadeusz Hołuj, Kazimierz Andrzej Jaworski and Marian Kubicki).

[109] Four large companies and more than 40 smaller groups were active throughout the war, even in the Gestapo's Pawiak prison in Warsaw and in Auschwitz; underground acting schools were also created.

[109] Underground actors, many of whom officially worked mundane jobs, included Karol Adwentowicz, Elżbieta Barszczewska, Henryk Borowski, Wojciech Brydziński, Władysław Hańcza, Stefan Jaracz, Tadeusz Kantor, Mieczysław Kotlarczyk, Bohdan Korzeniowski, Jan Kreczmar, Adam Mularczyk, Andrzej Pronaszko, Leon Schiller, Arnold Szyfman, Stanisława Umińska, Edmund Wierciński, Maria Wiercińska, Karol Wojtyła (who later became Pope John Paul II), Marian Wyrzykowski, Jerzy Zawieyski and others.

[113] Top Polish musicians and directors (Adam Didur, Zbigniew Drzewiecki, Jan Ekier, Barbara Kostrzewska, Zygmunt Latoszewski, Jerzy Lefeld, Witold Lutosławski, Andrzej Panufnik, Piotr Perkowski, Edmund Rudnicki, Eugenia Umińska, Jerzy Waldorff, Kazimierz Wiłkomirski, Maria Wiłkomirska, Bolesław Woytowicz, Mira Zimińska) performed in restaurants, cafes, and private homes, with the most daring singing patriotic ballads on the streets while evading German patrols.

Cafes, restaurants and private homes were turned into galleries or museums; some were closed, with their owners, staff and patrons harassed, arrested or even executed.

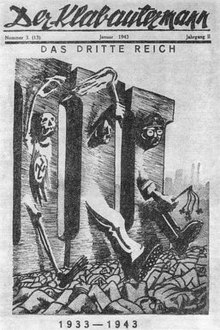

[115] Some artists worked directly for the Underground State, forging money and documents,[116][117] and creating anti-Nazi art (satirical posters and caricatures) or Polish patriotic symbols (for example kotwica).

[107] Headed by Antoni Bohdziewicz, the Home Army's Bureau of Information and Propaganda even created three newsreels and over 30,000 metres (98,425 ft) of film documenting the struggle.

"[128] Similarly, close-knit underground classes, from primary schools to universities, were renowned for their high quality, due in large part to the lower ratio of students to teachers.

Books by Tadeusz Borowski, Adolf Rudnicki, Henryk Grynberg, Miron Białoszewski, Hanna Krall and others; films, including those by Andrzej Wajda (A Generation, Kanał, Ashes and Diamonds, Lotna, A Love in Germany, Korczak, Katyń); TV series (Four Tank Men and a Dog and Stakes Larger than Life); music (Powstanie Warszawskie); and even comic books—all of these diverse works have reflected those times.

Polish historian Tomasz Szarota wrote in 1996:Educational and training programs place special emphasis on the World War II period and on the occupation.