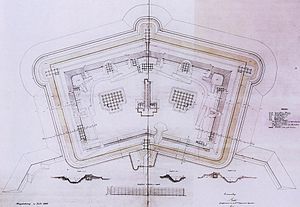

Polygonal fort

Before Vauban, besiegers had driven a sap towards the fort until they reached the glacis, where artillery could be positioned to fire directly on the scarp wall to make a breach.

The final refinement devised by Vauban was first used at the Siege of Ath in 1697, when he placed his artillery in the third parallel at a point close to the bastions, from where they could ricochet their shot along the inside of the parapet, dismounting the enemy guns and killing the defenders.

[4][5] Marc René, marquis de Montalembert (1714–1800) envisaged a system to prevent an opponent from establishing their parallel entrenchments by an overwhelming artillery barrage from a large number of guns, which were to be protected from return fire.

In 1780, Gerhard von Scharnhorst, a Hanoverian officer who went on to reform the Prussian Army, wrote that "All foreign experts in military and engineering affairs hail Montalembert's work as the most intelligent and distinguished achievement in fortification over the last hundred years.

It was, like d'Arcon's works, quadrilateral in plan, divided by a traverse with a circular tower keep in the rear and the surrounding ditch was protected by counterscarp galleries.

In 1809, Napoleon I asked him to write a handbook for the commanders of fortresses, which was published in the following year under the title De la défense des places fortes.

Only one stone casemated work, the Malakoff Tower, had been completed at the time of the allied landing and proved impervious to bombardment but was finally carried by French infantry in a coup de main.

British attempts to subdue the casemated Russian forts at Kronstadt and other fortifications in the Baltic Sea using conventional naval guns were far less successful.

[28] The British were apprehensive about a French invasion and in 1859 appointed the Royal Commission on the Defence of the United Kingdom to fortify the naval dockyards of southern England.

[29] The ring forts at Plymouth and Portsmouth were set further out than the Prussian designs they were based on and the casemates of coastal batteries were protected by composite armoured shields, tested to be resistant to the latest heavy projectiles.

[30] In the United States, it had been decided at an early stage that it would be impractical to provide landward fortifications for rapidly expanding cities but a considerable investment had been made in seaward defences in the form of multi-tiered casemated batteries, originally based on Montalembert's designs.

During the American Civil War of 1861 to 1865, the exposed masonry of these coastal batteries was found to be vulnerable to modern rifled artillery; Fort Pulaski was quickly breached by only ten of these guns.

On the other hand, the hastily constructed earthworks of landward fortifications proved much more resilient; the garrison of Fort Wagner were able to hold out for 58 days behind ramparts built of sand.

In the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, the invading Prussians were able to surround Paris after taking some of the outer forts and then bombard the city and its population with their rifled siege guns, without the need for a costly assault.

[32] In the aftermath of defeat, the French belatedly adopted a version of the polygonal system in a huge programme of fortification which commenced in 1874, under the direction of General Raymond Adolphe Séré de Rivières.

Polygonal forts typical of the Séré de Rivières system had guns protected by iron armour or revolving Mougin turrets.

[33] The programme involved the building of ring fortresses around Paris and to guard border crossings, often surrounding Vauban-era fortifications; the loss of Alsace-Lorraine to the Prussians created the need for a new defensive zone, described as a "barrier of iron".

The great powers of continental Europe were forced into vastly expensive programmes of fortification building and rebuilding to designs that were calculated to counter this latest threat.

[36] In France, the recently completed forts began to be refurbished, with thick layers of concrete reinforcing the ramparts and the roofs of magazines and accommodation spaces.

[37] Brialmont forts were triangular in plan and made extensive use of concrete with the main armament mounted in rotating turrets connected by tunnels.

This type of fortified position was called a Feste and was the result of the work of several German theorists but came to fruition under Colmar Freiherr von der Goltz who was appointed Inspector-General of Fortifications in 1898.

[40] At the start of the First World War in August 1914, the German Army crossed into neutral Belgium with the object of outflanking the French border fortifications.

[44] Another Russian ring fortress at Novogeorgievsk, later renamed Modlin, which guarded the northern approach to Warsaw, fell after a siege of 10 days in August 1915, with the loss of 90,000 men taken prisoner and 1,600 guns.

An initial infantry assault in September 1914 was repulsed with heavy Russian losses,[46] but the fortress was finally surrendered in the following March, after both a relief attempt and a breakout had failed.

[47] Following these failures, the French high command concluded that fixed fortifications were obsolete and they began the process of disarming their forts, since there was a grave shortage of medium artillery pieces in their field armies.

Rather than build new polygonal forts, the method chosen was a developed version of the German Feste system of dispersed strongpoints connected by tunnels to a central underground barracks, all concealed in the landscape.