Polypore

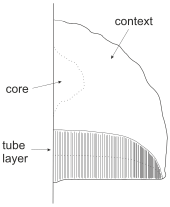

Polypores are a group of fungi that form large fruiting bodies with pores or tubes on the underside (with some exceptions).

[1] Over one thousand polypore species have been described to science,[2] but a large part of the diversity is still unknown even in relatively well-studied temperate areas.

Polypores and the related corticioid fungi are the most important agents of wood decay, playing a very significant role in nutrient cycling and aiding carbon dioxide absorption by forest ecosystems.

The name polypores is often used for a group that includes many of the hard or leathery fungi, which often lack a stipe, growing straight out of wood.

Reconstructions of family trees of fungi show that the poroid fruiting body has evolved numerous times in the past.

[6][7][8] The orders containing most polypore species are the Polyporales (genera such as Fomes, Polyporus and Trametes) and Hymenochaetales (e.g. Oxyporus, Phellinus and Trichaptum).

[9] Other polypore orders are the Agaricales, Amylocorticiales, Auriculariales, Boletales, Cantharellales, Gloeophyllales, Sebacinales, Thelephorales and Trechisporales.

[10][11] That number is bound to rise significantly through better understanding of evolutionary relationships between species and through mapping of uncovered diversity in the tropics.

[12] The fungal individual that develops the fruit bodies that are identified as polypores resides in soil or wood as mycelium.

Some species depend on a single tree genus (e.g. Piptoporus betulinus on birch, Perenniporia corticola on dipterocarps).

Forms of polypore fruit bodies range from mushroom-shaped to thin effused patches (crusts) that develop on dead wood.

A few polypores produce asexual spores (chlamydospores or conidia) in the upper surface of their cap (e.g. Echinopora aculeifera, Oligoporus ptychogaster) or without the presence of a sexual fruit body (e.g. Inonotus rickii, Heterobasidion spp.).

A couple of species where the tubes have not fused together in a honey-comb manner are variably classified as polypores or not (e.g. Porotheleum fimbriatum).

One of the more common genera, Ganoderma, can grow large thick shelves that may contribute to the death of the tree, and then feed off the wood for years after.

Their hardiness means they are very resilient and can live for quite a long time, with many species even developing beautiful multi-coloured circles of colour that are actually annual growth rings.

The fungal community in any single trunk may include both white-rot and brown-rot species, complementing each other's wood degradation strategies.

A rich fauna of insects, mites and other invertebrates feed on polypore mycelium and fruiting bodies, further providing food for birds and other larger animals.

Regional extinctions can happen relatively quickly and have been documented (for instance Antrodia crassa in North Europe[18]).

Some species prefer closed-canopy forest with a moist, even microclimate that could be disturbed for instance by logging (e.g. Skeletocutis jelicii).

Polypores make good indicators because they are relatively easy to find – many species produce conspicuous and long-lasting fruiting bodies – and because they can be identified in the field.

[23] The first indicator list of polypores widely used in forest inventories and conservation work was developed in northern Sweden in 1992 ("Steget före" method).

Polypores from the genus Hapalopilus have caused poisoning in several people with effects including kidney dysfunction and deregulation of central nervous system functions.

Beyond their traditional use in herbal medicine, contemporary research has suggested many applications of polypores for the treatment of illnesses related to the immune system and cancer recovery.