Pomerania in the Early Middle Ages

The southward movement of Germanic tribes during the migration period had left territory later called Pomerania largely depopulated by the 7th century.

[7][8] In late 960s, Polish Piasts acquired parts of eastern Pomerania, where the short-lived Diocese of Kołobrzeg (Kolberg) was installed in 1000 AD.

[1] The 5th century marks the climax of an era that is characterized by a gap between the latest Germanic and the earliest Slavic archaeological findings in Pomerania, that researchers until today cannot explain sufficiently.

[25] One school of thought, particularly popular among German researchers, sees the origins of these Slavs east of the Vistula and postulates a westward migration from there during the 6th and 7th centuries.

[26][29] It has been previously suggested that subsequent appearances of new material cultures were due to other waves of immigration, but it is presently interpreted as a mere technology transfer not involving mass migration.

[30] Slavic Feldberg type ceramics, found in a region comprising the Oder area up to the Persante (Parseta) river, as well as Mecklenburg and Brandenburg, are dated back to the 7th and 8th century.

[26] The Bavarian Geographer's anonymous medieval document, compiled in 830 in Regensburg, contains a list of the tribes in Central-Eastern Europe east of the Elbe.

One of the oldest gards is the stronghold of Dragovit, king of the Veleti, that was targeted by an expedition led by Charlemagne in 789 and is thought to be at modern Vorwerk near Demmin.

A Frankish document titled Bavarian Geographer (ca 845) mentions the tribes of Volinians[5] (Velunzani), Pyritzans[5] (Prissani), Ukrani (Ukri) and Veleti[5] (Wiltzi) around the lower Oder.

In contrast, the other tribe explicitly mentioned in contemporary chronicles, was that of the Pyritzans, who inhabited the area around Pyritz and Stargard but whose settlements numbered roughly only one for every twenty kilometers.

The first written record of any local Pomeranian ruler is the 1046 mention of Zemuzil[4][37] (in Polish literature also called Siemomysł) at an imperial meeting.

[40] This 13th-century chronicle reports that the later Hungarian king Bela I had fled to Mieszko II of Poland (mistaken for Casimir I), and defeated a Pomeranian duke ("Pomoranie ducem") in a duel.

[41] Pomeranian historian Adolf Hofmeister proposed that the record might nevertheless have a grain of truth in it, but in this case sees Wilk not as a universal ruler of Pomerania, but as a local or subordinate prince.

The languages of the southern part of the Polabian area, preserved as relics today in Upper and Lower Lusatia, occupy a place between the Lechitic and Czecho-Slovak groups.

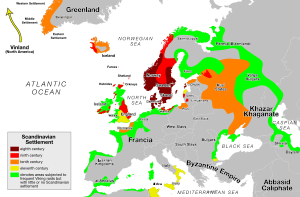

Major temple sites were: Viking Age Scandinavian settlements were set up along the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, primarily for trade purposes.

[46] Immigration going in both directions remains difficult to assess, but based on trade goods found within Slavic and Scandinavian settled areas belonging to both cultures, an exchange of population is hypothesized.

[34] Bardy-Świelubie differs from other emporia: The location is rather far from the coastline, and Bardy was built before 800, making it one of the earliest Slavic burghs in the coastal area.

[31] Reric, formerly located at Rerik on the Fischland-Darß-Zingst peninsula in Western Pomerania, has recently been identified as Groß Strömkendorf on the eastern coast of Wismar Bay in Mecklenburg.

[34] The exact ethnic composition of the settlements cannot be determined, it is thought that they had a multi-ethnic character - besides Scandinavians, a Slavic and Frisian presence has been suggested.

[citation needed] Scandinavian emporia and major Slavic burghs were set up primarily at junctions of long-distance trade routes.

[53] Another trade route connected Mecklenburg and Reric with Usedom and Wollin, running through Werle, Lüchow, Dargun, Demmin and Menzlin.

[60] Acquisition of loot and capture of people for slave trade were primary war aims in the many campaigns and expeditions of the Slavic tribes and invaders from outside Pomerania.

In the Battle of Recknitz ("Raxa") in 955, German and Rani forces commanded by Otto I of Germany suppressed an Obodrite revolt in the Billung march, instigated by Wichmann the Younger and his brother Egbert the One-Eyed[63] In 983, the area regained independence in an uprising initiated by the Liutizian federation.

[64] A similar pagan reaction in Denmark between 976[65] and 986,[8] initiated by Sven Forkbeard, forced his father Harald Bluetooth to exile to Wollin.

[9] Of all Liutizians, the Volinians were especially devoted to participation in the wars between the Holy Roman Empire and Poland from 1002 to 1018 to prevent Bolesław I from reinstating his rule in Pomerania.

[37] In the aftermath of the uprising of 983, Holy Roman Emperor Otto III sought to reinstate his marches and upheld good relations with Piast Poland, which was to be integrated in a reorganized empire ("renovatio imperii Romanorum").

[68] These plans, reaching a climax with the Congress of Gniezno in 1000 AD, were thwarted by Otto's death in 1002, the subsequent rapid expansion of the Piast realm, and the resulting change in Polish politics.

[68] Parts of the German clergy and nobility however did not approve this alliance, because it thwarted their ambitions to reintegrate the Lutician territories in their marches and bishoprics.

[71] Bolesław on the other hand prepared an anti-Lutician alliance which he termed "brotherhood in Christo", but at the same time tried to bribe the Luticians and have them carry out attacks on the empire.

[22] However, inner quarrels hindered the empire to pursue further conquests, and in 1073, Henry IV as well as his Saxon opponents offered alliances to the Luticians outbidding each other with favourable conditions and benefits.