Poor relief

In English and British history, poor relief refers to government and ecclesiastical action to relieve poverty.

Over the centuries, various authorities have needed to decide whose poverty deserves relief and also who should bear the cost of helping the poor.

Since the early 16th century legislation on poverty enacted by the Parliament of England, poor relief has developed from being little more than a systematic means of punishment into a complex system of government-funded support and protection, especially following the creation in the 1940s of the welfare state.

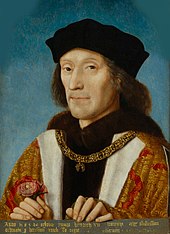

In the late 15th century, Parliament took action on the growing[citation needed] problem of poverty, focusing on punishing people for being "vagabonds" and for begging.

This involved the Dissolution of the Monasteries in England and Wales: the assets of hundreds of rich religious institutions, including their great estates, were taken by the Crown.

According to the historian Paul Slack, prior to the Dissolution "it has been estimated that monasteries alone provided 6,500 pounds a year in alms before 1537 [equivalent to £4,700,000 in 2023[2]]; and that sum was not made good by private benefactions until after 1580.

[5] "Two years' servitude and branding with a 'V' was the penalty for the first offense, and attempts to run away were to be punished by lifelong slavery and, there for a second time, execution.

These overseers were to 'gently ask' for donations for poor relief; refusal would ultimately result in a meeting with the local bishop, who would 'induce and persuade' the recalcitrant parishioners.

[1] However, even the Poor Act 1562 still suffered from shortcomings, because individuals could decide for themselves how much money to give in order to gain their freedom.

[1] Unlike the previous brutal punishments established by the Vagabonds Act 1547, these extreme measures were enforced with great frequency.

"Peddlers, tinkers, workmen on strike, fortune tellers, and minstrels" were not spared these gruesome acts of deterrence.

This law punished all able bodied men "without land or master" who would neither accept employment nor explain the source of their livelihood.

In addition, this Act of 1578[clarification needed] also extended the power of the church by stating that "vagrants were to be summarily whipped and returned to their place of settlement by parish constables.

Such methods included "owning or renting property above a certain value or paying parish rates, but also by completing a legal apprenticeship or a one-year service while unmarried, or by serving a public office" for that identical length of time.

With this increase in poverty, all charities operated by the Catholic Church were abolished due to the impact of protestant reformation.

By the mid to late 18th century most of the British Isles was involved in the process of industrialization in terms of production of goods, manner of markets[clarification needed] and concepts of economic class.

The increase in the price of grain most probably occurred as a result of a poor harvest in the years 1795–96, though at the time this was subject to great debate.

The authorities at Speenhamland approved a means-tested sliding scale of wage supplements in order to mitigate the worst effects of rural poverty.

The system allowed employers, including farmers and the nascent industrialists of the town, to pay below subsistence wages, because the parish would make up the difference and keep their workers alive.

[11] Following the onset of the Industrial Revolution, in 1834 the Parliament of the United Kingdom revised the Poor Relief Act 1601 after studying the conditions found in 1832.

Following the reformation of the Poor Laws in 1834, Ireland experienced a severe potato blight that lasted from 1845 to 1849 and killed an estimated 1.5 million people.

argue that as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was in its prime as an empire, it could have given more aid in the form of money, food or rent subsidies.