Port Chicago disaster

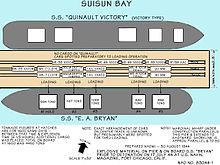

The town of Port Chicago was located on Suisun Bay in the estuary of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers, approximately 40 miles by water from the Golden Gate.

The munitions, destined for the Pacific Theater of Operations, were delivered by rail to the Port Chicago facility and then individually loaded by hand, crane, and winch onto cargo ships for further transport.

[10] The desired level had been set by Captain Nelson Goss, Commander Mare Island Navy Yard, whose jurisdiction included Port Chicago Naval Magazine.

[23] Commander Paul B. Cronk, head of a Coast Guard explosives-loading detail tasked with supervision of the working dock, warned the Navy that conditions were unsafe and ripe for disaster.

The ship arrived at the dock with no cargo, but was carrying a full load of 5,292 barrels (841,360 liters) of bunker C heavy fuel oil for its intended trip across the Pacific Ocean.

An officer who left the docks shortly after 10 p.m. noticed that the Quinault Victory′s propeller was slowly turning over and that the men of Division Three were having trouble pulling munitions from the rail cars because they had been packed so tightly.

Shattered glass and a rain of jagged metal and undetonated munitions caused more injuries among military personnel and civilians, although no one outside the immediate pier area was killed.

[33] Seismographs at the University of California, Berkeley sensed the two shock waves traveling through the ground, determining the second, larger event to be equivalent to an earthquake measuring 3.4 on the Richter magnitude scale.

[48] The government announced on August 23, 1951, that it had settled the last in a series of lawsuits relating to the disaster, when it awarded Sirvat Arsenian of Fresno, California, $9,700 for the death of her 26-year-old son, a merchant marine crewman killed in the blast.

Admiral Carleton H. Wright, Commander, 12th Naval District, spoke of the unfortunate deaths and the need to keep the base operating during a time of war.

He gave Navy and Marine Corps Medals for bravery to four officers and men who had successfully fought a fire in a rail car parked within a revetment near the pier.

"[50] Wright's report was passed to President Franklin D. Roosevelt by Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal who added his opinion that it was "mass fear" motivating the work stoppage.

The 258 African-American sailors in the ordnance battalion who continued to refuse to load ammunition were taken under guard to a barge that was used as a temporary military prison or "brig", despite having been built to accommodate only 75 men.

"[53] On August 11, 1944, the 258 men from the prison barge were marched to a nearby sports field and lectured by Admiral Wright, who told them that troops fighting on Saipan desperately needed the ammunition they were supposed to be loading and that continued refusal to work would be treated as mutinous conduct, which carried the death penalty in times of war.

The prosecution was led by Lieutenant Commander James F. Coakley, who had recently served as deputy chief prosecutor in Alameda County under district attorney Earl Warren.

[68] Later in the trial, Lieutenant Carleton Morehouse—Commander of Division Eight at Port Chicago—took the stand to say that at the first sign of problems on August 9, he assembled his men and read their names off alphabetically, ordering each man to work.

Tobin affirmed that one of the accused men from Division Two was permanently assigned the job of cook because he weighed 104 lb (47 kg) and was considered too small to safely load ammo.

His aim was to show the court that a conspiracy had taken place—the mass of accounts from officers and men appeared to support the conclusion that ringleaders and agitators had forced a rebellion against authority.

A black petty officer under Delucchi testified that he had heard no derogatory remarks or conspiratorial comments and that it had been a surprise to everybody when all of the men suddenly refused to march toward the docks on August 9.

[79] Marshall held another press conference on October 17 to announce that the NAACP was requesting a formal government investigation into the working conditions that had led the men to strike.

[81] In his closing argument, Coakley described a chronological sequence of mutinous occurrences, beginning at Camp Shoemaker shortly after the explosion when two and a half companies were mixed together for two weeks.

[82] Veltmann denied that there was a mutinous conspiracy, saying the men were in a state of shock stemming from the horrific explosion and the subsequent cleanup of human body parts belonging to their former battalion mates.

[86] Marshall obtained written permission from each of the 50 convicted men for him to appeal their case when it came up for review in Washington, DC in front of the Judge Advocate General of the Navy.

[94] In the months following the disaster, the Pittsburgh Courier, a newspaper with a large, nationwide subscriber base made up primarily of African Americans, related the incident and the subsequent mutiny trial in their Double V campaign, a push for victory over not just the Axis powers but also over racial inequality at home.

In the weeks following the latter incident, Fleet Admiral Ernest King and Secretary Forrestal worked with civilian expert Lester Granger on a plan for total integration of the races within the Navy.

[109] On July 10, 2008, Senator Barbara Boxer introduced legislation that would expand the memorial site by five acres (two hectares), if the land was judged safe for human health and was excess to the Navy's needs.

[117] The story of the Port Chicago 50 was the basis of Mutiny, a made-for-television movie written by James S. "Jim" Henerson and directed by Kevin Hooks, which included Morgan Freeman as one of three executive producers.

In 2015, award-winning writer Steve Sheinkin's The Port Chicago 50: Disaster, Mutiny, and the Fight for Civil Rights was a finalist for the 2014 National Book Award in Young People's Literature.

[121] The New York Times called it "just as suitable for adults" and noted that the "seriousness and breadth of Sheinkin’s research can be seen in his footnotes and lists of sources, which include oral histories, documentaries and Navy documents.

[123] The September 2022 issue of the Smithsonian Magazine had an article on the disaster entitled "A Deadly World War II Explosion Sparked Black Soldiers to Fight for Equal Treatment", written by historian Matthew F.