Portland Aerial Tram

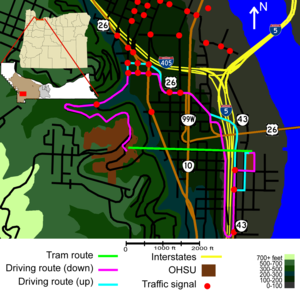

The alternative to riding the tram is via public roadways which require a 1.9-mile (3.1 km) route with numerous stoplights and intersections.

The lower (South Waterfront) station houses the tram's engines in a reinforced concrete basement[8] and also has ticketing facilities and the control room.

[11] The upper station is a freestanding steel and concrete tower 140 feet (42.7 m) above grade and houses the tram's counterweight.

[12] The 197-foot (60 m) intermediate tower allows the tram to gain elevation quickly once leaving the lower station to provide adequate clearance over Interstate 5.

[16] The tram cars were built by Gangloff AG,[17] of Bern in Switzerland, and were shaped and painted to look like the architectural firm's vision of "bubbles floating through the sky".

[3] Transportation officials originally estimated the tram would carry over 1,500 people a day, a figure that was expected to rise to 5,500 by 2030.

[27] In May 2022, the tram reopened to the general public after temporary restrictions on access that ultimately lasted more than two years were lifted.

[28] In late 2001, OHSU purchased property in the South Waterfront (then known as North Macadam) area, with plans to expand there.

After studying several ways, including shuttle buses, gondola lifts, tunnels, and even funiculars, to connect OHSU's primary campus on Marquam Hill with this area of planned expansion, the university sought city support of an aerial tram.

PDOT's assessment led to the same conclusion OHSU had reached earlier: an aerial tram was the preferred approach.

PDOT also recommended a second tram linking the Marquam Hill area with a nearby transit center on SW Barbur Boulevard.

In an effort to prevent future incidents, the engineering company designed a new permanent anchorage and safety tether system for the roof panels.

[41] While the taxpayer share has grown, OHSU paid for 85% of the total cost of the tram though it is operated as public transit facility.

[7] The initial budget for the tram, published in November 2002, was $15.5 million, excluding "soft costs" such as project management and architect's fees.

By October, The Oregonian reported that steel costs had led to bids pushing the project's price (with contingency funds) to $45 million.

The increased cost was expected to be met through South Waterfront urban renewal contributions which would have otherwise been spent on streets and parks.

The executive director of PATI was ousted,[44] and a month-long independent audit and risk assessment was undertaken; its results were published February 1, 2006.

[45] The audit revealed that OHSU managers knew as early as 2003 that the tram would cost well in excess of the original $15.5 million figure, partially due to a change in location of the upper terminal to accommodate planned hospital construction, but had withheld that information from city leaders.

This resulted in harsh public criticism of OHSU management, with city commissioner Randy Leonard accusing the university leadership of an "outrageous shell game...all at the expense of taxpayers".

OHSU protested vigorously, threatening a lawsuit should the tram be canceled, and claimed the city was responsible for making up any budget shortfall.

)[51] Even prior to the cost increases which plagued the design and construction of the tram, the project has been subject to criticism from the public.

Many residents of the Corbett-Terwilliger and Lair Hill neighborhoods, over which the tram passes, were concerned the cars would be an invasion of privacy and lead to lower property values.

[52] Initially, residents were promised that overhead power lines would be buried as part of the project, but as cost overruns mounted, this plan was scrapped.

[55] The city later offered to purchase homes directly under the tram route at fair market value.

"[61] Some critics, at the time of construction, cited the tram as an example of corporate welfare for OHSU with limited public benefit.

[63] Others argue that while the issues of increasing public costs are real, the importance of continued growth of OHSU for the city's economy must be factored in as well.

Not only is it the largest employer in the city, but OHSU is an important and effective vehicle to attract both federal funding,[64] totaling more than $168 million for 2005, and a highly skilled workforce to the area.

The growth in the current campus on the Marquam Hill is limited by access roads and parking, an expansion of which would likely cause more dramatic harm to the surrounding communities.

[67] According to city commissioner Adams, a cheaper alternative which would have changed the tower's designs to a lattice style used in electrical transmission towers, was not considered because the result would look like an "ugly ski lift at a bad ski resort"[68] and leave the city with what Adams called an "ugly postcard" that could last 100 years.

|

Route

Tram route

Driving route (down)

Driving route (up)

Interstate freeway

OHSU campus

Traffic signal

|

Elevation

700 feet (210 m)

500 feet (150 m) to 700 ft

300 feet (90 m) to 500 ft

200 feet (60 m) to 300 ft

100 feet (30 m) to 200 ft

0 to 100 ft

|