Postman's Park

A shortage of space for burials in London meant that corpses were often laid on the ground and covered over with soil, thus elevating the park above the streets which surround it.

Later she became disillusioned with the new tile manufacturer and, with her time and money increasingly occupied by the running of the Watts Gallery, she lost interest in the project, and only five further tablets were added during her lifetime.

In June 2009, a city worker, Jane Shaka (née Michele), via the Diocese of London added a new tablet to the Memorial, the first new addition for 78 years.

In November 2013 a free mobile app, The Everyday Heroes of Postman’s Park, was launched which documents the lives and deaths of those commemorated on the memorial.

[18] A Royal Commission established in 1842 to investigate the problem concluded that London's burial grounds were so overcrowded that it was impossible to dig a new grave without cutting through an existing one.

[15] A short distance south of the three burial grounds, on St. Martin's Le Grand, was the site of a collegiate church and sanctuary founded in 750 by Withu, King of Kent, expanded in 1056 by Ingebrian, Earl of Essex and issued with a Royal Charter in 1068 by William the Conqueror.

However, being owned by the parish, in 1891 ownership was formally passed to the newly formed City Parochial Foundation (CPF), which felt itself obliged under charity law to maximise its income from the land.

[15][36] The City of London had few open spaces, and the proposal to build on the north of the park was extremely unpopular with local residents, workers and social reformers.

Henry Fitzalan-Howard, the Postmaster-General, persuaded the Government to contribute £5,000 towards the cost,[15] and the clergy of St Botolph's Aldersgate launched an appeal in The Times for the remaining funds.

[37] The painter and sculptor George Frederic Watts and his second wife Mary Fraser Tytler had long been advocates of the idea of art as a force for social change.

[39][n 7] As the son of a piano maker, who reportedly despised the wealthy and powerful and twice refused a baronetcy,[40] Watts had long considered a national monument to the bravery of ordinary people.

[43][n 9] Watts by this stage had abandoned the idea of a colossal bronze figure, and proposed "a kind of Campo Santo", consisting of a covered way and marble wall inscribed with the names of everyday heroes, to be built in Hyde Park.

[38][n 10] On 13 October 1898 the appeal was relaunched, with the proposal that if the remaining £3,000 were raised, Watts would design and build a covered way, which in due course would be lined with memorial tablets to commemorate the bravery of ordinary people.

[46] St Botolph's Aldersgate secured the necessary funds to complete the purchase of the CPF land, and Watts agreed to pay the £700 (about £100,000 as of 2025) construction costs himself.

Watts was an acquaintance of William De Morgan, at that time one of the world's leading tile designers, and consequently found them easier and cheaper to obtain than engraved stone.

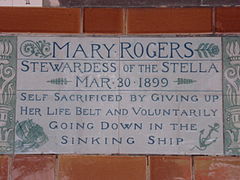

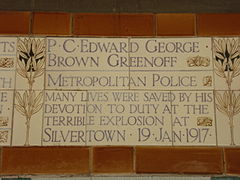

[49] The subjects of the 13 initial tiles had been personally selected by Watts, who had for many years maintained a list of newspaper reports of heroic actions potentially worthy of recognition.

He was hailed "The last great Victorian", and a memorial service was held in St Paul's Cathedral, 300 yards (270 m) south of Postman's Park, on 7 July 1904.

The Committee selected 24 names, 22 proposed by Watts before his death and two from press reports of 1905, and De Morgan was duly commissioned to produce the new set of tablets.

Alfred Smith, an officer of the Metropolitan Police, was patrolling Central Street in Finsbury, approximately 900 yards (820 m) directly north of Postman's Park.

[56] Mary Watts agreed and an appeal was launched in May 1929, aiming to raise funds to repair and restore the by now run-down loggia, and to install additional tablets.

Passenger was by this time working for a pottery business in Bushey Heath established by artist Ida Perrin, but Mary Watts persuaded him to produce a single panel in the style of De Morgan to fit into the empty space.

[65] Although parts of the ruins were cleared during a widening of King Edward Street after the Second World War, the remains of the nave of Christ Church Greyfriars became a public memorial in 1989; the tower is now office space.

Unusually for an English church, because of its location in a now mainly commercial area with few local residents, services are held on Tuesdays instead of the more traditional Sundays.

[70] On 5 June 1972, the western entrance of Postman's Park and the elaborate Gothic drinking fountain attached to the railings were Grade II listed, protecting them from further development.

[72] During the 1980s, however, prior to the opening of the nearby Barbican Centre and the regeneration of the local area, the Park and Memorial remained relatively neglected and unknown to the wider public.

[74] Leigh Pitt, a print technician from Surrey, had died on 7 June 2007 rescuing nine-year-old Harley Bagnall-Taylor who was drowning in a canal in Thamesmead.

In the story, the character Alice Ayres (played in the film by Natalie Portman) is asked for her name by Dan Woolf (Jude Law), in the course of their first meeting in Postman's Park.

The app employed image recognition technology and the built-in camera on the device to scan each tablet and then deliver the relevant information about the person.

The app was the result of collaboration between Prossimo Ventures Ltd[79] and Dr John Price of the University of Roehampton, supported by Creativeworks London, a Knowledge Exchange Hub for the Creative Economy funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC).

[60] In 2009 a 54th tablet was added, in the style of the Royal Doulton tiles, to commemorate print technician Leigh Pitt, the first addition to the wall for 78 years.