Marshall Plan

The goals of the United States were to rebuild war-torn regions, remove trade barriers, modernize industry, improve European prosperity and prevent the spread of communism.

Much more important were efforts to modernize European industrial and business practices using high-efficiency American models, reducing artificial trade barriers, and instilling a sense of hope and self-reliance.

[25] The Marshall Plan was one of the first elements of European integration, as it erased trade barriers and set up institutions to coordinate the economy on a continental level—that is, it stimulated the total political reconstruction of Western Europe.

The emerging doctrine of containment (as opposed to rollback) argued that the United States needed to substantially aid non-communist countries to stop the spread of Soviet influence.

In July 1947 Marshall scrapped Joint Chiefs of Staff Directive 1067, which was based on the Morgenthau Plan which had decreed "take no steps looking toward the economic rehabilitation of Germany [or] designed to maintain or strengthen the German economy."

[54] After the adjournment of the Moscow conference following six weeks of failed discussions with the Soviets regarding a potential German reconstruction, the United States concluded that a solution could not wait any longer.

The speech described the dysfunction of the European economy and presented a rationale for US aid: The modern system of the division of labor upon which the exchange of products is based is in danger of breaking down. ...

[58] In the audience at Harvard was International Law and Diplomacy graduate student Malcolm Crawford, who had just written his Master's thesis entitled "A Blueprint for the Financing of Post-War Business and Industry in the United Kingdom and Republic of France."

[63] After that, statements were made suggesting a future confrontation with the West, calling the United States both a "fascizing" power and the "center of worldwide reaction and anti-Soviet activity", with all U.S.-aligned countries branded as enemies.

Every country in Europe was invited, with the exceptions of Spain (a World War II neutral that had sympathized with the Axis powers) and the small states of Andorra, San Marino, Monaco, and Liechtenstein.

[69] A Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) report was read at the outset to set the heavily anti-Western tone, stating now that "international politics is dominated by the ruling clique of the American imperialists" which have embarked upon the "enslavement of the weakened capitalist countries of Europe".

[71] The report further claimed that "reactionary imperialist elements throughout the world, particularly in the United States, in Britain and France, had put particular hope on Germany and Japan, primarily on Hitlerite Germany—first as a force most capable of striking a blow at the Soviet Union".

[73] The meeting's chair, Andrei Zhdanov, who was in permanent radio contact with the Kremlin from whom he received instructions,[70] also castigated communist parties in France and Italy for collaboration with those countries' domestic agendas.

[74] Zhdanov warned that if they continued to fail to maintain international contact with Moscow to consult on all matters, "extremely harmful consequences for the development of the brother parties' work" would result.

The opposition argued that it made no sense to oppose communism by supporting the socialist governments in Western Europe; and that American goods would reach Russia and increase its war potential.

They called it "a wasteful 'operation rat-hole'"[76] Vandenberg, assisted by Senator Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. (R-Massachusetts) admitted there was no certainty that the plan would succeed, but said it would halt economic chaos, sustain Western civilization, and stop further Soviet expansion.

[82] The United Kingdom insisted on special status as a longstanding belligerent during the war, concerned that if it were treated equally with the devastated continental powers, it would receive virtually no aid.

Attempting to contain spreading Soviet influence in the Eastern Bloc, Truman asked Congress to restore a peacetime military draft and to swiftly pass the Economic Cooperation Act, the name given to the Marshall Plan.

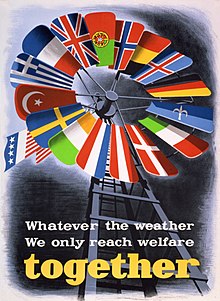

In the same year, the participating countries (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, West Germany, the United Kingdom, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, and the United States) signed an accord establishing a master financial-aid-coordinating agency, the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation (later called the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development or OECD), which was headed by Frenchman Robert Marjolin.

This way of operation held three advantages: the provision of U.S. goods to Europe without European dollar payments helped to narrow the dollar gap that strangled European reconstruction; the accumulated funds could be used for investments in long-term reconstruction (as happened in France and Germany) or for paying off a government's war debts (as in Great Britain); and the payments of the goods in local currencies helped to limit inflation by taking these funds temporarily out of circulation while they were held in the Special Accounts.

[108][109][110] With respect to Austria, Günter Bischof has noted that "the Austrian economy, injected with an overabundance of European Recovery Program funds, produced "miracle" growth figures that matched and at times surpassed the German ones.

"[111] Marshall aid in general and the counterpart funds in particular had a significant impact in Cold-War propaganda and economic matters in Western Europe, which most likely contributed to the declining appeal of domestic communist parties.

Through the Office of Policy Coordination money was directed toward support for labor unions, newspapers, student groups, artists and intellectuals, who were countering the anti-American counterparts subsidized by the communists.

Among the leading intellectuals from the US and Western Europe were writers, philosophers, critics and historians: Raymond Aron, Alfred Ayer, Franz Borkenau, Irving Brown, James Burnham, Benedetto Croce, John Dewey, Sidney Hook, Karl Jaspers, Arthur Koestler, Melvin J. Lasky, Richard Löwenthal, Ernst Reuter, Bertrand Russell, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., Ignazio Silone, Hugh Trevor-Roper, and Tennessee Williams.

[129] In addition to ERP grants, the Export-Import Bank (an agency of the US government) at the same time made long-term loans at low interest rates to finance major purchases in the US, all of which were repaid.

Though the Marshall Plan is seen as an act of compassion or sympathy for countries struggling after WWII, it is likely fear of slipping into another depression at home caused the United States to invest in diplomacy and pivot away from another economic calamity.

Austrian School economist Ludwig von Mises criticized the Marshall Plan in 1951, believing that "the American subsidies make it possible for [Europe's] governments to conceal partially the disastrous effects of the various socialist measures they have adopted".

The Marshall Plan grants were provided at a rate that was not much higher in terms of flow than the previous UNRRA aid and represented less than 3% of the combined national income of the recipient countries between 1948 and 1951,[124] which would mean an increase in GDP growth of only 0.3%.

Belgium, the country that relied earliest and most heavily on free-market economic policies after its liberation in 1944, experienced swift recovery and avoided the severe housing and food shortages seen in the rest of continental Europe.

Greenspan writes in his memoir The Age of Turbulence that Erhard's economic policies were the most important aspect of postwar Western European recovery, even outweighing the contributions of the Marshall Plan.