Preening

Ingestion of pollutants or disease-causing organisms during preening can lead to problems ranging from liver and kidney damage to pneumonia and disease transmission.

The use of the word preen to mean the tidying of a bird's feathers dates from Late Middle English.

[2] Despite spending considerable time in their efforts, they do not use proper techniques to groom effectively and may do a poor job overall as a result.

[4] Preening enables birds to remove dirt and parasites from their plumage, and assists in the waterproofing of feathers.

[9] Studies on multiple species have shown that they spend an average of more than 9% of each day on maintenance behaviours, preening occupying over 92% of that time, though this figure can be significantly higher.

[10][11] In most of the studied species where the bird's sex could be determined in the field, males spent more time preening than females, though this was reversed in ducks.

[13] To facilitate that care, many bird species have a preen or uropygial gland, which opens above the base of the tail feathers and secretes a substance containing fatty acids, water, and waxes.

[14] The gland is generally larger (in relation to body size) in waterbirds, including terns, grebes and petrels.

[15] Preen oil plays a role in reducing the presence of parasitic organisms, such as feather-degrading bacteria, lice and fungi, on a bird's feathers.

[19][20] Preen oil may play a part in protecting at least some species from some internal parasites; a study of the incidence of avian malaria in house sparrows found that uninfected birds had larger uropygial glands and higher antimicrobial activity in those glands than infected birds did.

[6] While most species have a preen gland, the organ is missing in the ratites (emu, ostriches, cassowaries, rheas and kiwis) and some neognath birds, including bustards, woodpeckers, a few parrots and pigeons.

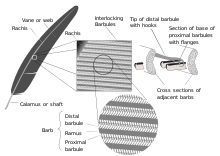

The nibbling action is the one used most often; it is more effective than stroking for applying preen oil, removing ectoparasites, rejoining unzipped barbules, and rearranging feathers.

During the breeding season, the preen oil of the great white pelican becomes red-orange, imparting a pink flush to the bird's plumage.

When all three eggs in their regular clutch were removed, the gulls showed a significant increase in the amount of time they spent preening.

Nesting Sandwich and common terns preen when they have been alarmed by a potential predator or when they have had an aggressive encounter with a neighbouring bird, for instance.

[49][50] Most allopreening activity concentrates on the head and neck, a lesser amount being directed towards the breast and mantle and an even smaller percentage applied to the flanks.

[53] Birds seeking allopreening adopt specific, ritualised postures to signal so; they may fluff their feathers out or put their heads down.

[54] Captive birds of social species that normally live in flocks, such as parrots, will regularly solicit preening from their human owners.

[58] Green wood hoopoes, a flocking species with a complex hierarchy, show similar frequencies of initiating and reciprocating allopreening of the head and neck regardless of social status, time of year or group size, which suggests that such activity is primarily related to feather hygiene.

[14] It is more common in species where both parents help to raise the offspring and correlates with an increased likelihood that partners will remain together for successive breeding seasons.

Evidence suggests this type of allopreening reduces social tension, and thus plays an important role in group cohesion.

[52] If birds are exposed to some pollutants, such as leaking petroleum, they can quickly lose the preen oil from their feathers.

[37] If waterbirds are exposed, they can lose both buoyancy and the ability to fly; this means they must swim constantly to stay warm and afloat (if they cannot reach land), and eventually die of exhaustion.

Studies done with black guillemots showed that even small amounts of ingested oil caused the birds physiological distress.

There is evidence that water-borne avian influenza virus is "captured" by the preen oil on feathers, providing a possible route for infection.

[64] Caged birds, particularly parrots, sometimes overpreen in response to being exposed to strong scents (such as nicotine or air fresheners) or as a result of neuropathy.

Reducing exposure to the offending odour, or treating the underlying cause of the neuropathy (such as injury, infection, or heavy metal intoxication) can help to eliminate the behaviour.

[65] Confining a bird with an incompatible or very dominant cage mate can lead to excessive allopreening, which can result in feather plucking or injury.