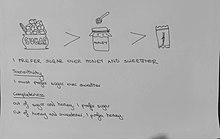

Preference

In psychology, preferences refer to an individual's attitude towards a set of objects, typically reflected in an explicit decision-making process.

[1] The term is also used to mean evaluative judgment in the sense of liking or disliking an object, as in Scherer (2005),[2] which is the most typical definition employed in psychology.

[5] Consequently, preference can be affected by a person's surroundings and upbringing in terms of geographical location, cultural background, religious beliefs, and education.

[6] In economics and other social sciences, preference refers to the set of assumptions related to ordering some alternatives, based on the degree of happiness, satisfaction, gratification, morality, enjoyment, or utility they provide.

The concept of preferences is used in post-World War II neoclassical economics to provide observable evidence in relation to people's actions.

The specific varieties are classified into three categories: 1) risk-averse, that is, equal gains and losses, with investors participating when the loss probability is less than 50%; 2) the risk-taking kind, which is the polar opposite of type 1); 3) Relatively risk-neutral, in the sense that the introduction of risk has no clear association with the decision maker's choice.

[16] The mathematical foundations of most common types of preferences — that are representable by quadratic or additive functions — laid down by Gérard Debreu[17][18] enabled Andranik Tangian to develop methods for their elicitation.

[21][22][23] In response to this, neoclassical economists argue that it provides a normative model for people to adjust and optimise their actions.

Heuristics are rules of thumb such as elimination by aspects which are used to make decisions rather than maximising the utility function.

[26] Economic biases such as reference points and loss aversion also violate the assumption of rational preferences by causing individuals to act irrationally.

In psychology, risk preference is occasionally characterised as the proclivity to engage in a behaviour or activity that is advantageous but may involve some potential loss, such as substance abuse or criminal action that may bring significant bodily and mental harm to the individual.

[29] In economics, risk preference refers to a proclivity to engage in behaviours or activities that entail greater variance returns, regardless of whether they be gains or losses, and are frequently associated with monetary rewards involving lotteries.

[38] Preference arises within the context of the principle maintaining that one of the main objectives in the winding up of an insolvent company is to ensure the equal treatment of creditors.

[39] The rules on preferences allow paying up their creditors as insolvency looms, but that it must prove that the transaction is a result of ordinary commercial considerations.

[39] Also, under the English Insolvency Act 1986, if a creditor was proven to have forced the company to pay, the resulting payment would not be considered a preference since it would not constitute unfairness.