Paul Kruger

Following the influx of thousands of predominantly British settlers with the Witwatersrand Gold Rush of 1886, "uitlanders" (foreigners) provided almost all of the South African Republic's tax revenues but lacked civic representation; Boer burghers retained control of the government.

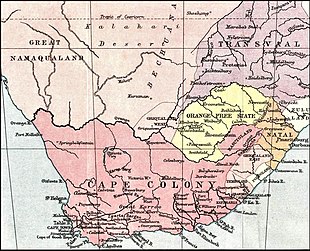

Boer discontent with aspects of British rule, such as the institution of English as the sole official language and the abolition of slavery in 1834, led to the Great Trek—a mass migration by Dutch-speaking "Voortrekkers" north-east from the Cape to the land on the far side of the Orange and Vaal rivers.

Kruger, aged 26, accompanied Pretorius and on 17 January 1852 was present at the conclusion of the Sand River Convention,[34] under which Britain recognised "the Emigrant Farmers" in the Transvaal as independent: they called themselves the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek ("South African Republic").

[37] Kruger's version of the story was that the Boers found an armoury and a workshop for repairing firearms in Livingstone's house and, interpreting this as a breach of Britain's promise at the Sand River not to arm tribal chiefs, confiscated them.

Having returned home, Kruger was surprised to receive a message urgently requesting his presence in the capital, the volksraad having recommended him as a suitable candidate; he replied that he was pleased to be summoned but his membership in the Dopper Church meant he could not enter politics.

In the 1872 election Kruger's preferred candidate, William Robinson, was decisively defeated by the Reverend Thomas François Burgers, a church minister from the Cape who was noted for his eloquent preaching but controversial for some because of his liberal interpretation of the scriptures.

Diamonds had been discovered in Griqua territory just north of the Orange River on the western edge of the Free State, arousing the interest of Britain and other countries; mostly British settlers, referred to by the Boers as uitlanders ("out-landers"), were flooding into the region.

In late 1876 Lord Carnarvon, Colonial Secretary under Benjamin Disraeli, gave Sir Theophilus Shepstone of Natal a special commission to confer with the South African Republic's government and, if he saw fit, annex the country.

[86] At the Colonial Office in Whitehall, Carnarvon and Kruger's own colleagues were astonished when, speaking through interpreters, he rose to what Meintjes calls "remarkable heights of oratory", averring that the annexation breached the Sand River Convention and went against the popular will in the Transvaal.

[91] The envoys met the British High Commissioner in Cape Town, Sir Bartle Frere,[91] and arrived in London on 29 June 1878 to find a censorious letter from Shepstone waiting for them, along with a communication that since Kruger was agitating against the government he had been dismissed from the executive council.

[89] Pretorius and Bok were swiftly released after Jorissen telegraphed the British Liberal politician William Ewart Gladstone, who had met Kruger's first deputation in London and had since condemned the annexation as unjust during his Midlothian campaign.

Kruger campaigned on the idea of an administration in which "God's Word would be my rule of conduct"—as premier he would prioritise agriculture, industry and education, revive Burgers's Delagoa Bay railway scheme, introduce an immigration policy that would "prevent the Boer nationality from being stifled", and pursue a cordial stance towards Britain and "obedient native races in their appointed districts".

[137] During a grand tour Kruger met William III of the Netherlands and his son the Prince of Orange, Leopold II of Belgium, President Jules Grévy of France, Alfonso XII of Spain, Luís I of Portugal, and in Germany Kaiser Wilhelm I and his Chancellor Otto von Bismarck.

[137] Kruger now held that Burgers had been "far ahead of his time"[137]—while reviving his predecessor's railway scheme, he also brought back the policy of importing officials from the Netherlands, in his view a means to strengthen the Boer identity and keep the Transvaal "Dutch".

Competition on the western frontier rose after Germany annexed South-West Africa; at the behest of the mining magnate and Cape MP Cecil Rhodes, Britain proclaimed a protectorate over Bechuanaland, including the Stellaland–Goshen corridor.

[145] The same year the volksraad passed constitutional revisions to remove the Nederduits Hervormde Kerk's official status, open the legislature to members of other denominations and make all churches "sovereign in their own spheres".

[149] Kruger expressed great satisfaction at the new arrivals' industry and respect for the state's laws,[141] but surmised that giving them full burgher rights might cause the Boers to be swamped by sheer weight in numbers, with the probable result of absorption into the British sphere.

[163] During the close-run campaign for the 1893 election, in which Kruger was again challenged by Joubert with the Chief Justice John Gilbert Kotzé as a third candidate, the President indicated that he was prepared to lower the 14-year residency requirement so long as it would not risk the subversion of the state's independence.

[171] Conferring with the Colonial Office, Rhodes pondered the co-ordination of an uitlander revolt in Johannesburg with British military intervention, and had a force of about 500 marshalled on the Bechuanaland–Transvaal frontier under Leander Starr Jameson, the Chartered Company's administrator in Matabeleland.

The Reform Committee's efforts to rally the uitlanders for revolt floundered, partly because not all of the mine-owners (or "Randlords") were supportive, and by 31 December the conspirators had raised a makeshift vierkleur over their headquarters at the offices of Rhodes's Gold Fields company, signalling their capitulation.

[180] Kruger shouted down talk of the death penalty for the imprisoned Jameson or a campaign of retribution against Johannesburg, challenging his more bellicose commandants to depose him if they disagreed, and accepted Robinson's proposed mediation with alacrity.

[180] After confiscating the weapons and munitions the Reform Committee had stockpiled, Kruger handed Jameson and his troops over to British custody and granted amnesty to all the Johannesburg conspirators except for 64 leading members, who were charged with high treason.

[182] Kruger's handling of the affair made his name a household word across the world and won him much support from Afrikaners in the Cape and the Orange Free State, who began to visit Pretoria in large numbers.

[n 25] The removal of Leyds to Europe marked the end of Kruger's longstanding policy of giving important government posts to Dutchmen; convinced of Cape Afrikaners' sympathy following the Jameson Raid, he preferred them from this point on.

[205][n 26] Jan Hendrik Hofmeyr of the Afrikaner Bond persuaded Kruger to make this fully retrospective (to immediately enfranchise all white men in the country seven years or more), but Milner and the South African League deemed this insufficient.

[209] The Boer commandos, including four of Kruger's sons, six sons-in-law and 33 of his grandsons, advanced quickly into the Cape and Natal, won a series of victories and by the end of October were besieging Kimberley, Ladysmith and Mafeking.

He planned to board the first outgoing steamer, the Herzog of the German East Africa Line, but was prevented from doing so when, at the behest of the local British Consul, the Portuguese Governor insisted that Kruger stay in port under house arrest.

[17] To admirers he was an astute reader of people, events and law who faithfully defended a maligned nation and became a tragic folk hero;[17] to critics he was "an anachronistic throwback", the stubborn, slippery guardian of an unjust cause and an oppressor of black Africans.

[17] "More nonsense has been written about him than anybody I know of", writes Meintjes, in whose view the true figure has been obscured by conflicting attempts to sabotage or whitewash his image—"a veritable bog of hostility and sentiment, prejudice and deification",[243] depicting Kruger as anything "from saint to stuffy mendacious savage".

[253] The underdevelopment of South African administrative law until the late 20th century was, Davenport asserts, the direct result of Kruger's censure and dismissal of Chief Justice Kotzé in 1898 over the question of judicial review.