Primate archaeology

First, in 1959 a skull identified as Zinjanthropus (now Paranthropus) boisei was found near Oldowan stone tools, and this led to the argument that this hominin could be a direct ancestor of modern humans.

[19] Recently, the idea that human ancestors have been responsible for intentionally making stone tools has also been put into question through primate archaeology research.

[20] Towards the end of the twentieth-century, archaeology shifted from a focus on typological classifications towards an interest in understanding the mechanisms behind the origins and subsequent evolution of stone tools.

[23] A couple of decades later, Kathy Schick and Nicholas Toth developed a similar experiment initially with a single captive, enculturated bonobo (Pan paniscus) named Kanzi to see whether he could copy Oldowan stone tool making.

[5] In 1994, Westergaard and Suomi decided to redo the Abang and Kanzi type of experiments but this time they ran a baseline study (no demonstrations) with a group of unenculturated monkeys - capuchins (Sapajus [Cebus] apella).

Researchers did not attempt further experiments involving non-human primates trying to make and use stone tools until around 2020 - when further baseline studies were run, this time with a focus on the performance of unenculturated apes.

[32] A few years later, in one of the Japanese macaque sites, a young female, later nicknamed "Imo", was observed washing a sweet potato in a small stream.

Through projects of this kind, Japanese primatology highlighted the importance of merging both field and experimental settings for the study of primate behavior and cognition.

Thus, it was Louis Leakey who encouraged Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, and Birutė Galdikas to study chimpanzee, gorilla and orangutan socio-ecology and behavior.

[39] On top of the experimental work with non-human primates towards the end of the twentieth century, archaeologists began to observe chimpanzees in the wild to try to understand their behaviour and possible spatial patterns present in their living spaces.

took place with the discovery of Panda 100, the first excavated chimpanzee nut-cracking archaeological site located in the Taï Forest, Ivory Coast and dated to around 4000 years ago.

[41] This site finally reinforced the idea that the combination of primatological and archaeological methods could shed light on both contemporary and past primate (human and non-human) behavior.

[47] Most of this work took place in Europe during the early twentieth century with examples such as the Anthropoid Station in Tenerife (Spain) dedicated to experimental research with large prosimians.

[28] Nonetheless, the most well-known example of the initial recognition of tool use in our closest relatives is Jane Goodall's report on chimpanzee termite fishing.

[21] When it comes to reconstructing past hominin behaviors, the use of non-human primates engaging in similar activities as the ones in the archaeological record is considered by some researchers as a viable methodology.

[3][53] Overall, the consensus points towards the use of multi-species comparative primate models given that different taxa provide distinct benefits when it comes to understanding early hominins.

[56] However, the "by-product hypothesis" has gained more attention after primate archaeology field experiments demonstrated that nut-cracking behavior can facilitate the production of reasonable numbers of sharp-edged flakes.

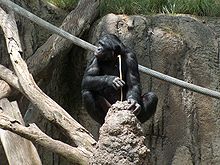

[36] Some of the most well-known tool use examples in chimpanzees include ant dipping, wood boring, honey fishing, leaf sponging, and nut-cracking.

[69] Moreover, even though there has been indirect evidence of capuchins using stones for foraging in rainforest habitats,[70][71] pounding behaviors such as nut-cracking seem to be associated with groups that spend most of their time on the ground or in savanna-like environments.

[69] For example, indirect evidence of several nut-cracking sites of S. xanthosternos has been reported in the State of Bahia, Brazil[81] However, tool use is more frequently observed amongst populations of S. apella[67][82][83][7] and S. libidinosus.

However, in 2007 this foraging behavior was observed in two long-tailed macaque populations inhabiting the Piak Nam Yai Island, Laem Son National Park in southern Thailand.

[citation needed] Although bonobos have been observed using tools in association with thirteen different behaviors only one of them, leaf sponging for drinking water, has a foraging purpose.

[116][117] In archaeology excavation is an essential element of the discipline because it allows archaeologists to trace when specific behaviors originated and their subsequent changes over time.

[2] Through excavation, archaeologists can obtain data on the chronology, the spatial distribution of the artefacts and the stratigraphic and depositional contexts of the site allowing them to reconstruct the natural and cultural events.

[119][98][120] The first non-human primate archaeological site was found in 2002 in the Taï Forest, Ivory Coast, and it was associated with chimpanzee tool use dating back 4000 years.

[98] Finally, another group of primate archaeologists discovered a capuchin nut-cracking site dated to around 2400 years ago at Serra da Capivara National Park, Brazil.

[121] Use-wear is a technique that consists of identifying the different damage marks present on stone tool edges to understand how toolmakers used these implements.

For example, through the use-wear analysis of percussive tools using 3D surface morphometrics, archaeologists discovered that different macaque behaviours leave specific traces on the stones.

[2][123] Lithic technological analysis entails the study of the different attributes present in stone tools such as flakes through measurements, qualitative observations and possible subsequent typological classifications.

Moreover, the occurrence of tool use and even the unintentional production of flakes in extant non-human primates questions the idea that only hominins were the sole creators of archaeological sites.