Cauchy stress tensor

and relates a unit-length direction vector e to the traction vector T(e) across an imaginary surface perpendicular to e: The SI base units of both stress tensor and traction vector are newton per square metre (N/m2) or pascal (Pa), corresponding to the stress scalar.

A graphical representation of this transformation law is the Mohr's circle for stress.

The Cauchy stress tensor is used for stress analysis of material bodies experiencing small deformations: it is a central concept in the linear theory of elasticity.

According to the principle of conservation of linear momentum, if the continuum body is in static equilibrium it can be demonstrated that the components of the Cauchy stress tensor in every material point in the body satisfy the equilibrium equations (Cauchy's equations of motion for zero acceleration).

At the same time, according to the principle of conservation of angular momentum, equilibrium requires that the summation of moments with respect to an arbitrary point is zero, which leads to the conclusion that the stress tensor is symmetric, thus having only six independent stress components, instead of the original nine.

However, in the presence of couple-stresses, i.e. moments per unit volume, the stress tensor is non-symmetric.

dividing the continuous body into two segments, as seen in Figure 2.1a or 2.1b (one may use either the cutting plane diagram or the diagram with the arbitrary volume inside the continuum enclosed by the surface

Following the classical dynamics of Newton and Euler, the motion of a material body is produced by the action of externally applied forces which are assumed to be of two kinds: surface forces

In specific fields of continuum mechanics the couple stress is assumed not to vanish; however, classical branches of continuum mechanics address non-polar materials which do not consider couple stresses and body moments.

: This equation means that the stress vector depends on its location in the body and the orientation of the plane on which it is acting.

of a particular material point, but also on the local orientation of the surface element as defined by its normal vector

, and can be resolved into two components (Figure 2.1c): According to the Cauchy Postulate, the stress vector

Cauchy's fundamental lemma is equivalent to Newton's third law of motion of action and reaction, and is expressed as The state of stress at a point in the body is then defined by all the stress vectors T(n) associated with all planes (infinite in number) that pass through that point.

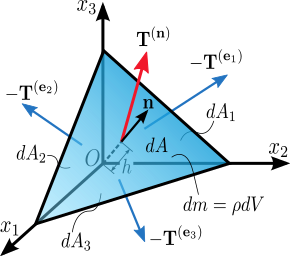

To prove this expression, consider a tetrahedron with three faces oriented in the coordinate planes, and with an infinitesimal area dA oriented in an arbitrary direction specified by a normal unit vector n (Figure 2.2).

The equilibrium of forces, i.e. Euler's first law of motion (Newton's second law of motion), gives: where the right-hand-side represents the product of the mass enclosed by the tetrahedron and its acceleration: ρ is the density, a is the acceleration, and h is the height of the tetrahedron, considering the plane n as the base.

The area of the faces of the tetrahedron perpendicular to the axes can be found by projecting dA into each face (using the dot product): and then substituting into the equation to cancel out dA: To consider the limiting case as the tetrahedron shrinks to a point, h must go to 0 (intuitively, the plane n is translated along n toward O).

As a result, the right-hand-side of the equation approaches 0, so Assuming a material element (see figure at the top of the page) with planes perpendicular to the coordinate axes of a Cartesian coordinate system, the stress vectors associated with each of the element planes, i.e. T(e1), T(e2), and T(e3) can be decomposed into a normal component and two shear components, i.e. components in the direction of the three coordinate axes.

Thus, using the components of the stress tensor or, equivalently, Alternatively, in matrix form we have The Voigt notation representation of the Cauchy stress tensor takes advantage of the symmetry of the stress tensor to express the stress as a six-dimensional vector of the form: The Voigt notation is used extensively in representing stress–strain relations in solid mechanics and for computational efficiency in numerical structural mechanics software.

The magnitude of the normal stress component σn of any stress vector T(n) acting on an arbitrary plane with normal unit vector n at a given point, in terms of the components σij of the stress tensor σ, is the dot product of the stress vector and the normal unit vector: The magnitude of the shear stress component τn, acting orthogonal to the vector n, can then be found using the Pythagorean theorem: where According to the principle of conservation of linear momentum, if the continuum body is in static equilibrium it can be demonstrated that the components of the Cauchy stress tensor in every material point in the body satisfy the equilibrium equations: where

For example, for a hydrostatic fluid in equilibrium conditions, the stress tensor takes on the form: where

, then Using the Gauss's divergence theorem to convert a surface integral to a volume integral gives For an arbitrary volume the integral vanishes, and we have the equilibrium equations According to the principle of conservation of angular momentum, equilibrium requires that the summation of moments with respect to an arbitrary point is zero, which leads to the conclusion that the stress tensor is symmetric, thus having only six independent stress components, instead of the original nine: where

Expanding this equation we have or in general This proves that the stress tensor is symmetric However, in the presence of couple-stresses, i.e. moments per unit volume, the stress tensor is non-symmetric.

of the stress tensor depend on the orientation of the coordinate system at the point under consideration.

However, the stress tensor itself is a physical quantity and as such, it is independent of the coordinate system chosen to represent it.

, the determinant matrix of the coefficients must be equal to zero, i.e. the system is singular.

, called the first, second, and third stress invariants, respectively, always have the same value regardless of the coordinate system's orientation.

Thus, Because of its simplicity, the principal coordinate system is often useful when considering the state of the elastic medium at a particular point.

Using just the part of the equation under the square root is equal to the maximum and minimum shear stress for plus and minus.

can be obtained similarly by assuming Thus, one set of solutions for these four equations is: These correspond to minimum values for

The equivalent stress is defined as Considering the principal directions as the coordinate axes, a plane whose normal vector makes equal angles with each of the principal axes (i.e. having direction cosines equal to

A note on the sign convention: The tetrahedron is formed by slicing a parallelepiped along an arbitrary plane n . So, the force acting on the plane n is the reaction exerted by the other half of the parallelepiped and has an opposite sign.

![{\displaystyle \left[{\begin{matrix}\sigma _{11}&\sigma _{12}\\\sigma _{21}&\sigma _{22}\end{matrix}}\right]=\left[{\begin{matrix}-10&10\\10&15\end{matrix}}\right].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c842dd4bd9c9055860c6c6ec3ef52637fd8cef89)