Principia Mathematica

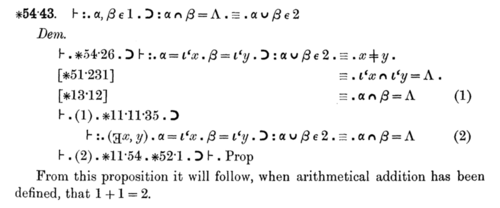

The Principia Mathematica (often abbreviated PM) is a three-volume work on the foundations of mathematics written by the mathematician–philosophers Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell and published in 1910, 1912, and 1913.

But as we advanced, it became increasingly evident that the subject is a very much larger one than we had supposed; moreover on many fundamental questions which had been left obscure and doubtful in the former work, we have now arrived at what we believe to be satisfactory solutions."

The theory of types adopts grammatical restrictions on formulas that rule out the unrestricted comprehension of classes, properties, and functions.

The effect of this is that formulas such as would allow the comprehension of objects like the Russell set turn out to be ill-formed: they violate the grammatical restrictions of the system of PM.

PM sparked interest in symbolic logic and advanced the subject, popularizing it and demonstrating its power.

[4] The Modern Library placed PM 23rd in their list of the top 100 English-language nonfiction books of the twentieth century.

Deeper theorems from real analysis were not included, but by the end of the third volume it was clear to experts that a large amount of known mathematics could in principle be developed in the adopted formalism.

A fourth volume on the foundations of geometry had been planned, but the authors admitted to intellectual exhaustion upon completion of the third.

[clarification needed] Kleene states that "this deduction of mathematics from logic was offered as intuitive axiomatics.

[10] Indeed, unlike a Formalist theory that manipulates symbols according to rules of grammar, PM introduces the notion of "truth-values", i.e., truth and falsity in the real-world sense, and the "assertion of truth" almost immediately as the fifth and sixth elements in the structure of the theory (PM 1962:4–36): Cf.

In the revised theory, the Introduction presents the notion of "atomic proposition", a "datum" that "belongs to the philosophical part of logic".

Dr Leon Chwistek [Theory of Constructive Types] took the heroic course of dispensing with the axiom without adopting any substitute; from his work it is clear that this course compels us to sacrifice a great deal of ordinary mathematics.

[13]It might be possible to sacrifice infinite well-ordered series to logical rigour, but the theory of real numbers is an integral part of ordinary mathematics, and can hardly be the subject of reasonable doubt.

However the position of the matching right or left parenthesis is not indicated explicitly in the notation but has to be deduced from some rules that are complex and at times ambiguous.

Here it is replaced by the modern symbol for conjunction "∧", thus The two remaining single dots pick out the main connective of the whole formula.

However, because of criticisms such as that of Kurt Gödel below, the best contemporary treatments will be very precise with respect to the "formation rules" (the syntax) of the formulas.

Small Greek letters (other than "ε", "ι", "π", "φ", "ψ", "χ", and "θ") represent classes (e.g., "α", "β", "γ", "δ", etc.)

[27] But before this notion can be defined, PM feels it necessary to create a peculiar notation "ẑ(φz)" that it calls a "fictitious object".

PM goes on to state that will continue to hang onto the notation "ẑ(φz)", but this is merely equivalent to φẑ, and this is a class.

Frank Ramsey tried to argue that Russell's ramification of the theory of types was unnecessary, so that reducibility could be removed, but these arguments seemed inconclusive.

Russell and Whitehead suspected that the system in PM is incomplete: for example, they pointed out that it does not seem powerful enough to show that the cardinal ℵω exists.

Gödel's first incompleteness theorem showed that no recursive extension of Principia could be both consistent and complete for arithmetic statements.

Gödel's second incompleteness theorem (1931) shows that no formal system extending basic arithmetic can be used to prove its own consistency.

Gödel 1944:126 describes it this way: This change is connected with the new axiom that functions can occur in propositions only "through their values", i.e., extensionally (...) [this is] quite unobjectionable even from the constructive standpoint (...) provided that quantifiers are always restricted to definite orders".

Gödel offered a "critical but sympathetic discussion of the logicistic order of ideas" in his 1944 article "Russell's Mathematical Logic".

[16]This section describes the propositional and predicate calculus, and gives the basic properties of classes, relations, and types.

This section constructs the ring of integers, the fields of rational and real numbers, and "vector-families", which are related to what are now called torsors over abelian groups.

The system of PM is roughly comparable in strength with Zermelo set theory (or more precisely a version of it where the axiom of separation has all quantifiers bounded).

[citation needed] The logical notation in PM was not widely adopted, possibly because its foundations are often considered a form of Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory.

[citation needed] The Modern Library placed PM 23rd in their list of the top 100 English-language nonfiction books of the twentieth century.