Prisoner's dilemma

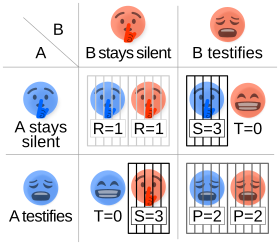

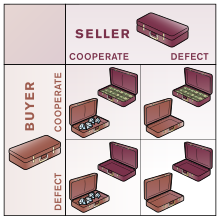

The prisoner's dilemma is a game theory thought experiment involving two rational agents, each of whom can either cooperate for mutual benefit or betray their partner ("defect") for individual gain.

In casual usage, the label "prisoner's dilemma" is applied to any situation in which two entities can gain important benefits by cooperating or suffer by failing to do so, but find it difficult or expensive to coordinate their choices.

William Poundstone described this "typical contemporary version" of the game in his 1993 book Prisoner's Dilemma: Two members of a criminal gang are arrested and imprisoned.

Since the collectively ideal result of mutual cooperation is irrational from a self-interested standpoint, this Nash equilibrium is not Pareto efficient.

[5][6] If the iterated prisoner's dilemma is played a finite number of times and both players know this, then the dominant strategy and Nash equilibrium is to defect in all rounds.

As shown by Robert Aumann in a 1959 paper,[7] rational players repeatedly interacting for indefinitely long games can sustain cooperation.

Conversely, as time elapses, the likelihood of cooperation tends to rise, owing to the establishment of a "tacit agreement" among participating players.

Axelrod invited academic colleagues from around the world to devise computer strategies to compete in an iterated prisoner's dilemma tournament.

For example, if a population consists entirely of players who always defect, except for one who follows the tit-for-tat strategy, that person is at a slight disadvantage because of the loss on the first turn.

[citation needed] In a stochastic iterated prisoner's dilemma game, strategies are specified in terms of "cooperation probabilities".

In the limit as n approaches infinity, M will converge to a matrix with fixed values, giving the long-term probabilities of an encounter producing j independent of i.

will be identical, giving the long-term equilibrium result probabilities of the iterated prisoner's dilemma without the need to explicitly evaluate a large number of interactions.

[22] Most work on the iterated prisoner's dilemma has focused on the discrete case, in which players either cooperate or defect, because this model is relatively simple to analyze.

Le and Boyd[24] found that in such situations, cooperation is much harder to evolve than in the discrete iterated prisoner's dilemma.

In a continuous prisoner's dilemma, if a population starts off in a non-cooperative equilibrium, players who are only marginally more cooperative than non-cooperators get little benefit from assorting with one another.

By contrast, in a discrete prisoner's dilemma, tit-for-tat cooperators get a big payoff boost from assorting with one another in a non-cooperative equilibrium, relative to non-cooperators.

[26] An important difference between climate-change politics and the prisoner's dilemma is uncertainty; the extent and pace at which pollution can change climate is not known.

[27] Thomas Osang and Arundhati Nandy provide a theoretical explanation with proofs for a regulation-driven win-win situation along the lines of Michael Porter's hypothesis, in which government regulation of competing firms is substantial.

Often animals engage in long-term partnerships; for example, guppies inspect predators cooperatively in groups, and they are thought to punish non-cooperative inspectors.

The final case, where one engages in the addictive behavior today while abstaining tomorrow, has the problem that (as in other prisoner's dilemmas) there is an obvious benefit to defecting "today", but tomorrow one will face the same prisoner's dilemma, and the same obvious benefit will be present then, ultimately leading to an endless string of defections.

[31] In The Science of Trust, John Gottman defines good relationships as those where partners know not to enter into mutual defection behavior, or at least not to get dynamically stuck there in a loop.

Anti-trust authorities want potential cartel members to mutually defect, ensuring the lowest possible prices for consumers.

[45] Although metaphorical, Garrett Hardin's tragedy of the commons may be viewed as an example of a multi-player generalization of the prisoner's dilemma: each villager makes a choice for personal gain or restraint.

The commons are not always exploited: William Poundstone, in a book about the prisoner's dilemma, describes a situation in New Zealand where newspaper boxes are left unlocked.

In 1988, John Werner, a first-year student, successfully organized his classmates to boycott the exam, demonstrating a practical application of game theory and the prisoner's dilemma concept.

[50][51] These examples highlight how the prisoner's dilemma can be used to explore cooperative behavior and strategic decision-making in educational contexts.

This may better reflect real-world scenarios, the researchers giving the example of two scientists collaborating on a report, both of whom would benefit if the other worked harder.

The main theme of the series has been described as the "inadequacy of a binary universe" and the ultimate antagonist is a character called the All-Defector.

In The Adventure Zone: Balance during The Suffering Game subarc, the player characters are twice presented with the prisoner's dilemma during their time in two liches' domain, once cooperating and once defecting.

In the eighth novel from the author James S. A. Corey, Tiamat's Wrath, Winston Duarte explains the prisoner's dilemma to his 14-year-old daughter, Teresa, to train her in strategic thinking.