Proletkult

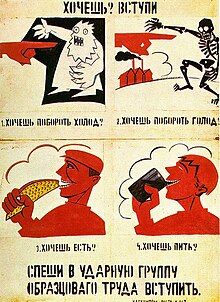

Proletkult aspired to radically modify existing artistic forms by creating a new, revolutionary working-class aesthetic, which drew its inspiration from the construction of modern industrial society in backward, agrarian Russia.

[1] The censorship apparatus of the Tsarist regime had stumbled briefly during the upheaval, broadening horizons, but the revolution had ultimately failed, resulting in dissatisfaction and second-guessing, even within Bolshevik Party ranks.

In the aftermath of the Tsar's reassertion of authority a radical political tendency known as the "Left Bolsheviks" emerged, stating their case in opposition to party leader Lenin.

[3] In addition, together with the celebrated Gorky, Lunacharsky hoped to found a "human religion" around the idea of socialism, motivating individuals to serve a greater good outside of their own narrow self-interests.

[4] Working along similar lines simultaneously was Lunacharsky's brother-in-law Bogdanov, who even in 1904 had published a weighty philosophical tome called Empiriomonism which attempted to integrate the ideas of non-Marxist thinkers Ernst Mach and Richard Avenarius into the socialist edifice.

Bogdanov believed that the socialist society of the future would require forging a fundamentally new perspective of the role of science, ethics, and art with respect to the individual and the state.

Lenin saw Bogdanov and the "god-building" movement with which he was associated as purveyors of a reborn philosophical idealism that stood in diametrical opposition to the fundamental materialist foundation of Marxism.

So disturbed was Lenin that he spent much of 1908 combing more than 200 books to pen a thick polemical volume in reply — Materialism and Empirio-Criticism: Critical Comments on a Reactionary Philosophy.

During the first decade of the 20th Century Bogdanov wrote two works of utopian science fiction about socialist societies on Mars, both of which were rejected by Lenin as attempts to smuggle "Machist idealism" into the radical movement.

[12] The aim of unifying the cultural and educational activities of the Russian labour movements first occurred at the Agitation Collegium of the Executive Committee of the Petrograd Soviet which met on 19 July 1917 with 120 participants.

[15] Also playing a key role was the future Chairman of the Organising Bureau of the National Proletkult, Pavel Lebedev-Polianskii, another former member of Bogdanov and Lunacharsky's émigré political group.

[17] Clubs and cultural societies sprung up affiliated with newly empowered factories, unions, cooperatives, and workers' and soldiers' councils, in addition to similar groups attached to more formal institutions such as the Red Army, the Communist Party, and its youth section.

[17] The new government of Soviet Russia was quick to understand that these rapidly proliferating clubs and societies offered a potentially powerful vehicle for the spread of the radical political, economic, and social theories it favored.

[17] The chief cultural authority of the Soviet state was its People's Commissariat of Education (Narkompros), a bureaucratic apparatus which quickly came to include no fewer than 17 different departments.

[21] In this political environment any centrally-devised scheme for a division of authority between Narkompros and the federated artistic societies of Proletkult remained largely a theoretical exercise.

[23] Moscow Proletkult, in which Alexander Bogdanov played a leading role, attempted to extend its independent sphere of control even further than the Petrograd organization, addressing questions of food distribution, hygiene, vocational education, and issuing a call for establishment of a proletarian university at its founding convention in February 1918.

[32] While those favoring autonomy were in the majority at the first national conference, the ongoing problem of organizational finance remained a real one, as historian Lynn Mally has observed: Although the Proletkult was autonomous, it still expected Narkompros to foot the bills.

But because financial dependence on the state clearly contradicted the organization's claims to independence, the central leaders held out the hope that their affiliates would soon discover their own means of support.

[34] Bukharin provided favorable coverage for Proletkult during the organization's formative period, welcoming the idea that the group represented a "laboratory of pure proletarian ideology" with a legitimate claim to independence from Soviet governmental control.

The nature and function of Proletkult was described by Platon Kerzhentsev, one of the movement's top leaders in 1919: The task of the 'Proletkults' is the development of an independent proletarian spiritual culture, including all areas of the human spirit — science, art, and everyday life.

[46]Proletkult's theorists generally espoused a hardline economic determinism, arguing that only purely working class organizations were capable of advancing the cause of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

[47] An early editorial from the official Proletkult journal Proletarskaia Kultura (Proletarian Culture) demanded that "the proletariat start right now, immediately, to create its own socialist forms of thought, feeling, and daily life, independent of alliances or combinations of political forces.

"[48] In the view of Alexander Bogdanov and other Proletkult theoreticians, the arts were not the province of a specially gifted elite, but rather were the physical output of individuals with a set of learned skills.

[42] Despite the organization's rhetoric about its proletarian exclusivity, however, the movement was guided by intellectuals throughout its entire brief history, with its efforts to promote workers from the bench to leadership positions largely unsuccessful.

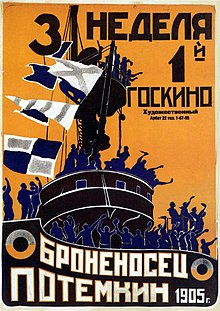

[51] Petrograd Proletkult opened a large central studio early in 1918 which staged a number of new and experimental works with a view to inspiring similar performances in other amateur theaters around the city.

"[52] Conventional modes of performance were discouraged, in favor of unconventional stagings designed to promote "mass action" — including public processions, festivals, and social dramas.

"[55] More specifically, Lenin had profound misgivings about the entire institution of Proletkult, viewing it as (in historian Sheila Fitzpatrick's words) "an organization where futurists, idealists, and other undesirable bourgeois artists and intellectuals addled the minds of workers who needed basic education and culture..."[56] Lenin also may have had political misgivings about the organization as a potential base of power for his long-time rival Alexander Bogdanov or for ultra-radical "Left Communists" and the syndicalist dissidents who comprised the Workers' Opposition.

Dissident groups such as the so-called Workers' Opposition and the Democratic Centralists emerged in the Communist Party, widespread dissatisfaction among the peasantry over forced grain requisitioning resulted in isolated uprisings.

[59] Ever since 1918 Nadezhda Krupskaya — the wife of Vladimir Lenin — had sought to rein in Proletkult and integrate it under the agency in which she herself played a leading role, the Adult Education Division of Narkompros.

[62] Spurred to action by Lenin, in the fall of 1920 the governing Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (bolsheviks) began to take an active interest in the relationship of Proletkult with other Soviet institutions for the first time.