Property tax in the United States

Most local governments in the United States impose a property tax, also known as a millage rate, as a principal source of revenue.

[23] Most jurisdictions impose the tax on some stated portion of fair market value, referred to as an assessment ratio.

[29] Generally, such state provides a board of equalization or similar body to determine values in cases of disputes between jurisdictions.

In this approach, the original or replacement cost of a property is reduced by an allowance for decline in value (depreciation) of improvements.

[27] Selection of an appropriate discount rate in determining present values is a key judgmental factor influencing valuation under this approach.

In Louisiana, no formal notice is required; instead, the assessor "opens" the books to allow property owners to view the valuations.

Some jurisdictions provide that notification is made by publishing a list of properties and values in a local newspaper.

Nearly all jurisdictions provide a homestead exemption reducing the taxable value, and thus tax, of an individual's home.

[51] Some jurisdictions provide broad exemptions from property taxes for businesses located within certain areas, such as enterprise zones.

[61] In most states, the taxing authority can seize the property and offer it for sale, generally at a public auction.

Assessors may be elected, appointed, hired, or contracted, depending on rules within the jurisdiction, which may vary within a state.

[62] The tax assessors in some states are required to pass certain certification examinations and/or have a certain minimum level of property valuation experience.

Some state courts have held that this uniformity and equality requirement does not prevent granting individualized tax credits (such as exemptions and incentives).

In many states the uniformity and equality provisions apply only to property taxes, leading to significant classification problems.

[63][page needed] Many of these uniformity clauses emerged in the antebellum era, originating in the Southern United States.

Historian Robin Einhorn argues that these clauses were designed to ensure that enslaved people were not taxed at a higher rate than other forms of property.

[66] During the period from 1796 until the Civil War, a unifying principle developed: "the taxation of all property, movable and immovable, visible and invisible, or real and personal, as we say in America, at one uniform rate.

Hard times during the Great Depression led to high delinquency rates and reduced property tax revenues.

After World War II, some states replaced exemptions with "circuit breaker" provisions limiting increases in value for residences.

The market value of undeveloped real estate reflects a property's current use as well as its development potential.

As a city expands, relatively cheap and undeveloped lands (such as farms, ranches, private conservation parks, etc.)

This, along with a higher sale price, increases the incentive to rent or sell agricultural land to developers.

On the other hand, a property owner who develops a parcel must thereafter pay a higher tax, based on the value of the improvements.

Because these persons have high-assets accumulated over time, they have a high property tax liability, although their realized income is low.

It has been suggested that these two beliefs are not incompatible — it is possible for a tax to be progressive in general but to be regressive in relation to minority groups.

In an effort to relieve the frequently large tax burdens on existing owners, particularly those with fixed incomes such as the elderly and those who have lost their jobs, communities have introduced exemptions.

Since there is no national database that links home ownership with Social Security numbers, landlords sometimes gain homestead tax credits by claiming multiple properties in different states, and even their own state, as their "principal residence", while only one property is truly their residence.

[70] In 2005, several US Senators and Congressmen were found to have erroneously claimed "second homes" in the greater Washington, D.C. area as their "principal residences", giving them property tax credits to which they were not entitled.

[71] Undeserved homestead exemption credits became so ubiquitous in the state of Maryland that a law was passed in the 2007 legislative session to require validation of principal residence status through the use of a social security number matching system.

In Rhode Island efforts are being made to modify revaluation practices to preserve the major benefit of property taxation, the reliability of tax revenue, while providing for what some view as a correction of the unfair distribution of tax burdens on existing owners of property.

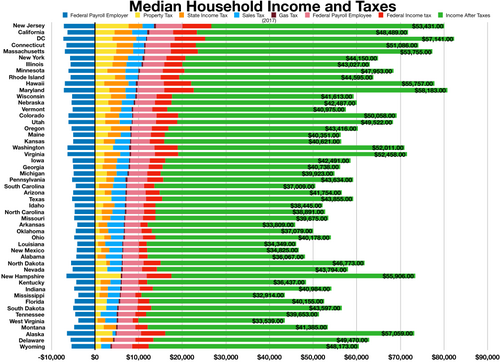

-$500, $1,000, $2,000, $3,000, $4,000, $5,000, $6,000, $7,000+