Protectorate of Wallis and Futuna

It was established at the request of the customary kings, under the influence of Catholic Marist missionaries who had converted the population in 1840-42 and sought French protection against the advance of Protestants in the region.

Residing in Wallis, he is responsible for maintaining law and order, managing the budget and collecting taxes, building infrastructure, and also has the power to validate the appointment of customary kings.

[6] The Wallis and Futuna islands are structured around village chiefdoms headed by a customary “king” (hau in Wallisian, sau in Futunian), chosen from among the noble families ('aliki).

As Jean-Claude Roux sums up, “behind the missionary screen, a delicate game between sailors, consuls, colonists, and merchants was going to be played for a long time, for the control of the South Pacific archipelagos.”[13] The aim was to counter the influence of the Tongans, who had recently converted to Methodism and were making several attempts to extend their religion to Wallis.

Under the influence of the Marist Fathers, the Wallisian sovereign (Lavelua) made an initial request to France for a protectorate in February 1842, then again in October of the same year, by addressing the various ship captains who docked at Wallis.

[19] However, for Jean-Claude Roux, by 1900 “Wallis and Futuna were no longer of any strategic value.”[20] It wasn't until the late 1890s that the two islands began to show some economic interest, in the production of copra.

[26] In the early 1930s, Wallis and Futuna were hit by a parasite, oryctes rhinoceros, which contaminated coconut palms and led to a collapse in copra production, the territory's main export at the time.

Jean Joseph David also petitioned the population for the annexation of Wallis and Futuna by France, but the authorities in Paris and Nouméa refused, deeming the project too costly.

[35] Cut off from other French territories and surrounding islands (Fiji, Samoa, Tonga) in the hands of the Allies, Wallis and Futuna suffered complete isolation for seventeen months.

On March 16, 1941, Vrignaud and the bishop supported the election of King Leone Matekitoga by the royal families, although the latter refused to pledge allegiance to Marshal Pétain.

This period had profound repercussions on Wallisian society: the American soldiers introduced numerous materials and built infrastructures that still bear their mark today.

A true consumer frenzy swept over the island despite regulatory efforts by the residency.”[40] The protectorate's tax revenues greatly increased due to customs duties on American products.

The Wallisians faced economic difficulties: subsistence farming had been neglected, coconut plantations were abandoned due to the lack of copra exports, and poultry populations were threatened with extinction.

[49] The post-World War II era was a period of economic crisis: the production of copra, the archipelago’s only commercial crop, collapsed in Wallis, forcing the population to return to subsistence farming.

[50] In Wallis, governance relies on a delicate balance between customary authorities (the Lavelua and traditional chiefs), the clergy, the small French administration, and a handful of merchants.

Anthropologist Sophie Chave-Dartoen notes that "the organization of Wallisian society is rooted in an intimate relationship between people and the land inherited from their ancestors."

[10] Each village is led by a chief (pule kolo), to whom the residents of a household ('api) pledge allegiance, providing services during customary ceremonies and participating in collective labor (fatogia).

Scholars Dominique Pechberty and Epifania Toa describe this as a genuine syncretism,[57][note 2] while Frédéric Angleviel uses the term “inculturation.”[49]In 1871, Queen Amelia Tokagahahau enacted the Code of Wallis (Tohi fono o Uvea).

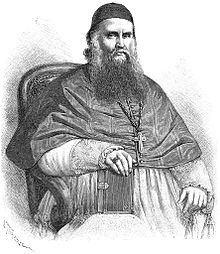

Drafted by Bishop Pierre Bataillon, this legislative text, written in Wallisian, precisely defined the composition of the chieftainship and established the king as the sole supreme leader.

However, as Frédéric Angleviel noted, “The residency generally sought to maintain good relations with the mission, which was a key element of local life.”[49] The construction of infrastructure in the 1950s, such as schools and dispensaries, was positively received by the clergy.

“The mission was favorable to anything that could improve the lives of its faithful, as long as Christian morality was upheld.”[61] In Futuna, the Marists maintained a particularly strong influence in the absence of a French administration.

[23] However, in a society characterized by a system of gift and counter-gift exchanges—where monetary transactions were minimal—the assertion of power relied on the distribution of conspicuous goods (mats, pigs, etc.)

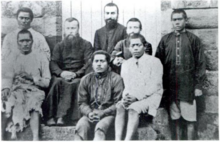

[16] Due to limited human resources, the resident often delegated responsibilities to a missionary, effectively making the clergyman the island's sole official representative.

After a period of total isolation, which led to shortages of basic goods and a return to subsistence agriculture, the arrival of American troops in 1942 transformed the local economy.

[67] Following World War II, New Caledonian companies began recruiting workers from Wallis and Futuna, initiating labor migration that became an essential feature of the island's economic landscape.

However, this tax was only implemented during World War I, partly due to the intervention of Bishop Joseph Félix Blanc, who convinced the king in a period of national unity.

In 1930, the oryctes pest devastated coconut plantations in Wallis, causing a collapse in copra production and making the tax much harder to collect.

Many words referring to European goods and techniques entered the local languages (e.g., mape for “map,” suka for “sugar,” sitima for “motorboat” from steamer, pepa for “paper,” and motoka for “car” from motor-car).

[78] Pierre-Yves Le Meur and Valelia Muni Toke note that by the 2010s, the era of the protectorate, "though not without instances of colonial violence", seems to have been largely forgotten by the inhabitants.

This perception is particularly significant because, in the 2010s, the French government expressed interest in exploiting mineral resources in the seabed within Wallis and Futuna's exclusive economic zone.