Protocol Wars

Separately, proprietary data communication protocols emerged, most notably IBM's Systems Network Architecture in 1974 and Digital Equipment Corporation's DECnet in 1975.

In the early 1960s, J. C. R. Licklider proposed the idea of a universal computer network while working at Bolt Beranek & Newman (BBN) and, later, leading the Information Processing Techniques Office (IPTO) at the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA, later, DARPA) of the US Department of Defense (DoD).

Independently, Paul Baran at RAND in the US and Donald Davies at the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) in the UK invented new approaches to the design of computer networks.

[38] On the ARPANET, the starting point in 1969 for connecting a host computer (i.e., a user) to an IMP (i.e., a packet switch) was the 1822 protocol, which was written by Bob Kahn.

[30][42] Steve Crocker, a graduate student at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) formed a Network Working Group (NWG) that year.

"[nb 1] Under the auspices of Leonard Kleinrock at UCLA,[43] Crocker led other graduate students, including Jon Postel, in designing a host-host protocol known as the Network Control Program (NCP).

[nb 3][45][46] After approval by Barry Wessler at ARPA,[47] who had ordered certain more exotic elements to be dropped,[48] the NCP was finalized and deployed in December 1970 by the NWG.

There, engineers developed a packet-switching protocol from basic principles for an Experimental Packet Switched Service (EPSS) based on a virtual call capability.

[51][52] Rémi Després started work in 1971, at the CNET (the research center of the French PTT), on the development of an experimental packet switching network, later known as RCP.

[66] Le Lann proposed the sliding window scheme for achieving reliable error and flow control on end-to-end connections.

[70][71] Louis Pouzin's ideas to facilitate large-scale internetworking caught the attention of ARPA researchers through the International Network Working Group (INWG), an informal group established by Steve Crocker, Pouzin, Davies, and Peter Kirstein in June 1972 in Paris, a few months before the International Conference on Computer Communication (ICCC) in Washington demonstrated the ARPANET.

[86] At Stanford, its specification, RFC 675, was written in December by Cerf with Yogen Dalal and Carl Sunshine as a monolithic (single layer) design.

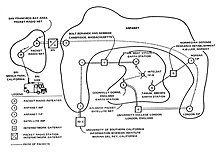

[70] The following year, testing began through concurrent implementations at Stanford, BBN and University College London,[87] but it was not installed on the ARPANET at this time.

[73][63][nb 6] The fourth biennial Data Communications Symposium later that year included presentations from Davies, Pouzin, Derek Barber, and Ira Cotten about the current state of packet-switched networking.

At the conference, Pouzin said pressure from European PTTs forced the Canadian DATAPAC network to change from a datagram to virtual circuit approach,[36] although historians attribute this to IBM's rejection of their request for modification to their proprietary protocol.

He spoke about the "political significance of the [datagram versus virtual circuit] controversy," which he saw as "initial ambushes in a power struggle between carriers and the computer industry.

"[63] After Larry Roberts and Barry Wessler left ARPA in 1973 to found Telenet, a commercial packet-switched network in the US, they joined the international effort to standardize a protocol for packet switching based on virtual circuits shortly before it was finalized.

[94] With contributions from the French, British, and Japanese PTTs, particularly the work of Rémi Després on RCP and TRANSPAC, along with concepts from DATAPAC in Canada, and Telenet in the US, the X.25 standard was agreed by the CCITT in 1976.

[75] Vint Cerf said Roberts turned down his suggestion to use TCP when he built Telenet, saying that people would only buy virtual circuits and he could not sell datagrams.

[60] The CYCLADES project, however, was shut down in the late 1970s for budgetary, political and industrial reasons and Pouzin was "banished from the field he had inspired and helped to create".

[119][120][121] The Coloured Book protocols, developed by British Post Office Telecommunications and the academic community at UK universities, gained some acceptance internationally as the first complete X.25 standard.

[135] In the US, the National Science Foundation (NSF), NASA, and the United States Department of Energy (DoE) all built networks variously based on the DoD model, DECnet, and IP over X.25.

[146][141] Hubert Zimmermann, and Charles Bachman as chairman, played a key role in the development of the Open Systems Interconnections reference model.

[147][153] Although the OSI model shifted power away from the PTTs and IBM towards smaller manufacturer and users,[147] the "strategic battle" remained the competition between the ITU's X.25 and proprietary standards, particularly SNA.

Proprietary protocols were based on closed standards and struggled to adopt layering while X.25 was limited in terms of speed and higher-level functionality that would become important for applications.

Vint Cerf formed the Internet Configuration Control Board (ICCB) in 1979 to oversee the network's architectural evolution and field technical questions.

[162][146][163] Historian Andrew L. Russell wrote that Internet engineers such as Danny Cohen and Jon Postel were accustomed to continual experimentation in a fluid organizational setting through which they developed TCP/IP.

In response, Vint Cerf performed a striptease in a three-piece suit while presenting to the 1992 Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) meeting, revealing a T-shirt emblazoned with "IP on Everything".

[165] Cerf later said the social culture (group dynamics) that first evolved during the work on the ARPANET was as important as the technical developments in enabling the governance of the Internet to adapt to the scale and challenges involved as it grew.

[3] Martin Campbell-Kelly and Valérie Schafer have focused on British and French contributions as well as global and international considerations in the development of packet switching, internetworking and the Internet.