Proton decay

Some beyond-the-Standard-Model grand unified theories (GUTs) explicitly break the baryon number symmetry, allowing protons to decay via the Higgs particle, magnetic monopoles, or new X bosons with a half-life of 1031 to 1036 years.

[3] To date, all attempts to observe new phenomena predicted by GUTs (like proton decay or the existence of magnetic monopoles) have failed.

[4][5][6] Quantum gravity[7] (via virtual black holes and Hawking radiation) may also provide a venue of proton decay at magnitudes or lifetimes well beyond the GUT scale decay range above, as well as extra dimensions in supersymmetry.

Such examples include neutron oscillations and the electroweak sphaleron anomaly at high energies and temperatures that can result between the collision of protons into antileptons[12] or vice versa (a key factor in leptogenesis and non-GUT baryogenesis).

One of the outstanding problems in modern physics is the predominance of matter over antimatter in the universe.

The universe, as a whole, seems to have a nonzero positive baryon number density – that is, there is more matter than antimatter.

This has led to a number of proposed mechanisms for symmetry breaking that favour the creation of normal matter (as opposed to antimatter) under certain conditions.

This imbalance would have been exceptionally small, on the order of 1 in every 1010 particles a small fraction of a second after the Big Bang, but after most of the matter and antimatter annihilated, what was left over was all the baryonic matter in the current universe, along with a much greater number of bosons.

Most grand unified theories explicitly break the baryon number symmetry, which would account for this discrepancy, typically invoking reactions mediated by very massive X bosons (X) or massive Higgs bosons (H0).

The rate at which these events occur is governed largely by the mass of the intermediate X or H0 particles, so by assuming these reactions are responsible for the majority of the baryon number seen today, a maximum mass can be calculated above which the rate would be too slow to explain the presence of matter today.

These estimates predict that a large volume of material will occasionally exhibit a spontaneous proton decay.

Proton decay is one of the key predictions of the various grand unified theories (GUTs) proposed in the 1970s, another major one being the existence of magnetic monopoles.

Both concepts have been the focus of major experimental physics efforts since the early 1980s.

To date, all attempts to observe these events have failed; however, these experiments have been able to establish lower bounds on the half-life of the proton.

Despite the lack of observational evidence for proton decay, some grand unification theories, such as the SU(5) Georgi–Glashow model and SO(10), along with their supersymmetric variants, require it.

Additional decay modes are available (e.g.: p+ → μ+ + π0 ), both directly and when catalyzed via interaction with GUT-predicted magnetic monopoles.

As further experiments and calculations were performed in the 1990s, it became clear that the proton half-life could not lie below 1032 years.

Many books from that period refer to this figure for the possible decay time for baryonic matter.

More recent findings have pushed the minimum proton half-life to at least 1034–1035 years, ruling out the simpler GUTs (including minimal SU(5) / Georgi–Glashow) and most non-SUSY models.

The maximum upper limit on proton lifetime (if unstable), is calculated at 6×1039 years, a bound applicable to SUSY models,[16] with a maximum for (minimal) non-SUSY GUTs at 1.4×1036 years.

[16](part 5.6) Although the phenomenon is referred to as "proton decay", the effect would also be seen in neutrons bound inside atomic nuclei.

Neutrons bound inside a nucleus have an immensely longer half-life – apparently as great as that of the proton.

[19] Supersymmetric GUTs with reunification scales around µ ~ 2×1016 GeV/c2 yield a lifetime of around 1034 yr, roughly the current experimental lower bound.

All of these operators violate both baryon number (B) and lepton number (L) conservation but not the combination B − L. In GUT models, the exchange of an X or Y boson with the mass ΛGUT can lead to the last two operators suppressed by

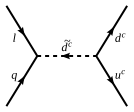

In supersymmetric extensions (such as the MSSM), we can also have dimension-5 operators involving two fermions and two sfermions caused by the exchange of a tripletino of mass M. The sfermions will then exchange a gaugino or Higgsino or gravitino leaving two fermions.

The overall Feynman diagram has a loop (and other complications due to strong interaction physics).

In the absence of matter parity, supersymmetric extensions of the Standard Model can give rise to the last operator suppressed by the inverse square of sdown quark mass.