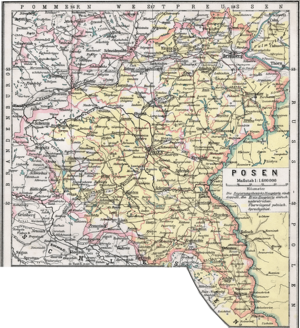

Province of Posen

After World War I, Posen was briefly part of the Free State of Prussia within Weimar Germany, but was dissolved in 1920 when the Greater Poland Uprising broke out and most of its territory was incorporated into the Second Polish Republic.

The land is mostly flat, drained by two major watershed systems; the Noteć (German: Netze) in the north and the Warta (Warthe) in the center.

Ice Age glaciers left moraine deposits and the land is speckled with hundreds of "finger lakes", streams flowing in and out on their way to one of the two rivers.

The three-field system was used to grow a variety of crops, primarily rye, sugar beet, potatoes, other grains, and some tobacco and hops.

It was officially ended in Prussia (see Freiherr vom Stein) in 1810 (1864 in Congress Poland), but lingered in some practices until the late 19th century.

In many places, windmills dotted the landscape, reminding one of the earliest settlers, the Dutch, who began the process of turning unproductive river marshes into fields.

Prussia then administered this province as the semi-autonomous Grand Duchy of Posen, which lost most of its exceptional status already after the 1830 November Uprising in Congress Poland,[1] as the Prussian authorities feared a Polish national movement which would have swept away the Holy Alliance system in Central Europe.

Instead Prussian Germanisation measures increased under Oberpräsident Eduard Heinrich von Flottwell, who had replaced Duke-governor Antoni Radziwiłł.

A first Greater Poland Uprising in 1846 failed, as the leading insurgents around Karol Libelt and Ludwik Mierosławski were reported to the Prussian police and arrested for high treason.

Their trial at the Berlin Kammergericht court gained them enormous popularity even among German national liberals, who themselves were suppressed by the Carlsbad Decrees.

King Frederick William IV of Prussia as well as the new Prussian commissioner, Karl Wilhelm von Willisen, promised a renewed autonomy status.

[5] Poles suffered from discrimination by the Prussian state; numerous oppressive measures were implemented to eradicate the Polish community's identity and culture.

[6][7] The Polish inhabitants of Posen, who faced discrimination and even forced Germanization, favored the French side during the Franco-Prussian War.

[10] Under German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck renewed Germanisation policies began, including an increase of the police, a colonization commission, and the Kulturkampf.

The German Eastern Marches Society (Hakata) pressure group was founded in 1894 and in 1904, special legislation was passed against the Polish population.

With the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, most of the province, composed of the areas with a Polish majority, was ceded to Poland and was reformed as the Poznań Voivodeship.

The majority-German populated remainder (with Bomst, Fraustadt, Neu Bentschen, Meseritz, Tirschtiegel (partially), Schwerin, Blesen, Schönlanke, Filehne, Schloppe, Deutsch Krone, Tütz, Schneidemühl, Flatow, Jastrow, and Krojanke—about 2,200 km2 (850 sq mi)) was merged with the western remains of former West Prussia and was administered as Posen-West Prussia[1] with Schneidemühl as its capital.

Following Germany's defeat in World War in 1945, at Stalin's demand all of the German territory east of the newly established Oder–Neisse line of the Potsdam Agreement was either turned over to the Poland or the Soviet Union.

This was despite efforts of the government in Berlin to prevent it, establishing the Settlement Commission to buy land from Poles and make it available for sale only to Germans.

The province's large number of resident Germans resulted from constant immigration since the Middle Ages, when the first settlers arrived in the course of the Ostsiedlung.