Pseudo-Euclidean space

In mathematics and theoretical physics, a pseudo-Euclidean space of signature (k, n-k) is a finite-dimensional real n-space together with a non-degenerate quadratic form q.

Such a quadratic form can, given a suitable choice of basis (e1, …, en), be applied to a vector x = x1e1 + ⋯ + xnen, giving

Unlike in a Euclidean space, such a vector can be non-zero, in which case it is self-orthogonal.

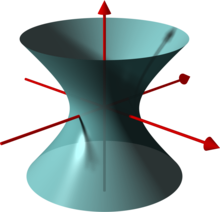

If the quadratic form is indefinite, a pseudo-Euclidean space has a linear cone of null vectors given by { x | q(x) = 0 }.

The quadratic form q corresponds to the square of a vector in the Euclidean case.

Hence terms norm and distance are avoided in pseudo-Euclidean geometry, which may be replaced with scalar square and interval respectively.

Though, for a curve whose tangent vectors all have scalar squares of the same sign, the arc length is defined.

[5] Such "rotations" preserve the form q and, hence, the scalar square of each vector including whether it is positive, zero, or negative.

Such a hypersurface, called a quasi-sphere, is preserved by the appropriate indefinite orthogonal group.

There are no orthonormal bases in a pseudo-Euclidean space for which the bilinear form is indefinite, because it cannot be used to define a vector norm.

For a (positive-dimensional) subspace[6] U of a pseudo-Euclidean space, when the quadratic form q is restricted to U, following three cases are possible:

One of the most jarring properties (for a Euclidean intuition) of pseudo-Euclidean vectors and flats is their orthogonality.

But the definition from the previous subsection immediately implies that any vector ν of zero scalar square is orthogonal to itself.

Hence, the isotropic line N = ⟨ν⟩ generated by a null vector ν is a subset of its orthogonal complement N⊥.

The formal definition of the orthogonal complement of a vector subspace in a pseudo-Euclidean space gives a perfectly well-defined result, which satisfies the equality dim U + dim U⊥ = n due to the quadratic form's non-degeneracy.

Generally, for a (d+ + d− + d0)-dimensional subspace U consisting of d+ positive and d− negative dimensions (see Sylvester's law of inertia for clarification), its orthogonal "complement" U⊥ has (k − d+ − d0) positive and (n − k − d− − d0) negative dimensions, while the rest d0 ones are degenerate and form the U ∩ U⊥ intersection.

The parallelogram law takes the form Using the square of the sum identity, for an arbitrary triangle one can express the scalar square of the third side from scalar squares of two sides and their bilinear form product: This demonstrates that, for orthogonal vectors, a pseudo-Euclidean analog of the Pythagorean theorem holds: Generally, absolute value |⟨x, y⟩| of the bilinear form on two vectors may be greater than √|q(x)q(y)|, equal to it, or less.

Unlike Euclidean angle, it takes values from [0, +∞) and equals to 0 for antiparallel vectors.

Unlike properties above, where replacement of q to −q changed numbers but not geometry, the sign reversal of the quadratic form results in a distinct Clifford algebra, so for example Cl1,2(R) and Cl2,1(R) are not isomorphic.

Like with a Euclidean structure, there are raising and lowering indices operators but, unlike the case with Euclidean tensors, there is no bases where these operations do not change values of components.