Pseudoforest

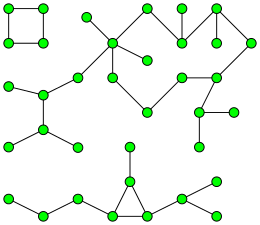

Pseudoforests are sparse graphs – their number of edges is linearly bounded in terms of their number of vertices (in fact, they have at most as many edges as they have vertices) – and their matroid structure allows several other families of sparse graphs to be decomposed as unions of forests and pseudoforests.

A cycle in an undirected graph is a connected subgraph in which each vertex is incident to exactly two edges, or is a loop.

If one augments a 1-tree by adding an edge that connects one of its vertices to a newly added vertex, the result is again a 1-tree, with one more vertex; an alternative method for constructing 1-trees is to start with a single cycle and then repeat this augmentation operation any number of times.

[12] That is, if c is a constant with 0 < c < 1/2, and Pc(n) is the probability that choosing uniformly at random among the n-vertex graphs with cn edges results in a pseudoforest, then Pc(n) tends to one in the limit for large n. However, for c > 1/2, almost every random graph with cn edges has a large component that is not unicyclic.

The number of maximal directed pseudoforests on n vertices, allowing self-loops, is nn, because for each vertex there are n possible endpoints for the outgoing edge.

André Joyal used this fact to provide a bijective proof of Cayley's formula, that the number of undirected trees on n nodes is nn − 2, by finding a bijection between maximal directed pseudoforests and undirected trees with two distinguished nodes.

Cycle detection, the problem of following a path in a functional graph to find a cycle in it, has applications in cryptography and computational number theory, as part of Pollard's rho algorithm for integer factorization and as a method for finding collisions in cryptographic hash functions.

Konyagin et al. have made analytical and computational progress on graph statistics.

[16] Martin, Odlyzko, and Wolfram[17] investigate pseudoforests that model the dynamics of cellular automata.

Another early application of functional graphs is in the trains used to study Steiner triple systems.

Trains have been shown to be a powerful invariant of triple systems although somewhat cumbersome to compute.

[23] More simply, if multigraphs with self-loops are considered, there is only one forbidden minor, a vertex with two loops.

Each edge is marked with a capacity (how much of a commodity can be converted per unit time), a flow multiplier (the conversion rate between commodities), and a cost (how much loss or, if negative, profit is incurred per unit of conversion).

The task is to determine how much of each commodity to convert via each edge of the flow network, in order to minimize cost or maximize profit, while obeying the capacity constraints and not allowing commodities of any type to accumulate unused.

The intermediate solutions arising from this algorithm, as well as the eventual optimal solution, have a special structure: each edge in the input network is either unused or used to its full capacity, except for a subset of the edges, forming a spanning pseudoforest of the input network, for which the flow amounts may lie between zero and the full capacity.

This fact plays a key role in the analysis of cuckoo hashing, a data structure for looking up key-value pairs by looking in one of two hash tables at locations determined from the key: one can form a graph, the "cuckoo graph", whose vertices correspond to hash table locations and whose edges link the two locations at which one of the keys might be found, and the cuckoo hashing algorithm succeeds in finding locations for all of its keys if and only if the cuckoo graph is a pseudoforest.

[26] Pseudoforests also play a key role in parallel algorithms for graph coloring and related problems.