Psychology of art

The psychology of art is the scientific study of cognitive and emotional processes precipitated by the sensory perception of aesthetic artefacts, such as viewing a painting or touching a sculpture.

[citation needed] His most important contribution in this respect was his attempt to theorize the question of Einfuehlung or "empathy", a term that was to become a key element in many subsequent theories of art psychology.

[citation needed] Numerous artists in the twentieth century began to be influenced by the psychological argument, including Naum Gabo, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, and somewhat Josef Albers and György Kepes.

The French adventurer and film theorist André Malraux was also interested in the topic and wrote the book La Psychologie de l'Art (1947-9) later revised and republished as The Voices of Silence.

Dewey himself played a seminal role in setting up the program of the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, which became famous for its attempt to integrate art into the classroom experience.

The seminal work was Gestalt Therapy: Excitement and Growth in the Human Personality (1951), that was co-authored by Fritz Perls, Paul Goodman, and Ralph Hefferline.

He felt that it was likely a sort of defence mechanism against the negative effects of neuroses, a way to translate that energy into something socially acceptable, which could entertain and please others.

Erwin Panofsky, who had a tremendous[peacock prose] impact on the shape of art history in the US, argued that historians should focus less on what is seen and more on what was thought.

[21] Art is considered to be a subjective field, in which one composes and views artwork in unique ways that reflect one's experience, knowledge, preference, and emotions.

[24][25][26] Similar to how these terms are used in software design, "bottom-up" refers to how information in the stimulus is processed by the visual system into colors, shapes, patterns, etc.

[24][25] Bottom-up factors identified in how art is appreciated include abstract vs figurative painting, form, complexity, symmetry and compositional balance, laterality and movement.

[24] Top-down influences identified as being related to art appreciation include prototypicality, novelty, additional information like titles, and expertise.

[27] Researchers have examined the role of terror management theory (TMT) concerning meaning and the aesthetic experience of abstract versus figurative art.

This theory suggests that humans, like all life forms are biologically oriented toward continued survival but are uniquely aware that their lives will inevitably end.

TMT reveals that modern art is often disliked because it lacks appreciable meaning, and is thus incompatible with the underlying terror management motive to maintain a meaningful conception of reality.

The mortality salience condition consisted of two opened ended questions about emotions and physical details concerning the participant's own death.

Individuals chronically disposed to clear, simple, and unambiguous knowledge express a particularly negative aesthetic experience towards abstract art, due to the void of meaningful content.

Using kindergarten to college aged participants, researchers tested viewers' aesthetic preference when comparing an original piece of art with its mirror image.

[41] Additionally, a historical preference to artistically display or render half-left profiles in single subject portraits across various media, found in almost 5,000 works of art, suggests that differential left/right hemisphere activation proclivities in artists of a particular sex and handedness might influence aesthetic composition [42][43] Complexity can literally be defined as being "made up of a large number of parts that have many interactions.

[51] Previous research, suggest that this trend of complexity could also be associated with ability to understand, in which observers prefer artwork that is not too easy or too difficult to comprehend.

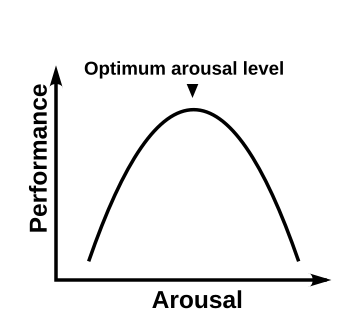

[52] Other research both confirms and disconfirms predictions that suggest that individual characteristics such as artistic expertise and training can produce a shift in the inverted U-shape distribution.

[51] A general trend shows that the relationship between image complexity and pleasantness ratings form an inverted-U shape graph (see Expertise section for exceptions).

[24][57] Humans innately tend to see and have a visual preference for symmetry, an identified quality yielding a positive aesthetic experience that uses an automatic bottom-up factor.

[61] In order to determine whether meaning mattered for a given stimuli, participants were asked to view pairs of objects and make a forced-choice decision, evaluating their preference.

The influence of symmetry on aesthetic preferences has been examined across a wide variety of stimuli including faces, shapes, patterns, objects, and paintings.

[24] Just as symmetry relates to aesthetic preference and reflects an intuitive sense for how things 'should' appear, the overall balance of a given composition contributes to judgments of the work.

[82] They also found that naive participants rated popular art as more pleasant and warm and the high-art paintings as more unpleasant and cold, while experts showed the opposite pattern.

An experiment examining how these factors combine to create aesthetic appreciation included experts and nonexperts rating their emotional valence, arousal, liking, and comprehension of abstract, modern, and classical art works.

[92] Changing title information about a painting does not seem to affect eye movement when looking at it or how subjects interpret its spatial organization.

Descriptive titles increase understanding of abstract art only when viewers are presented with an image for a very short period of time (less than 10 seconds).