Psychophysics

Modern applications rely heavily on threshold measurement,[3] ideal observer analysis, and signal detection theory.

For instance, in the realm of digital signal processing, insights from psychophysics have guided the development of models and methods for lossy compression.

[5] He coined the term "psychophysics", describing research intended to relate physical stimuli to the contents of consciousness such as sensations (Empfindungen).

As a physicist and philosopher, Fechner aimed at developing a method that relates matter to the mind, connecting the publicly observable world and a person's privately experienced impression of it.

Fechner's work was studied and extended by Charles S. Peirce, who was aided by his student Joseph Jastrow, who soon became a distinguished experimental psychologist in his own right.

In particular, a classic experiment of Peirce and Jastrow rejected Fechner's estimation of a threshold of perception of weights.

[8][9][10][11] On the basis of their results they argued that the underlying functions were continuous, and that there is no threshold below which a difference in physical magnitude would be undetected.

[12] Jastrow wrote the following summary: "Mr. Peirce’s courses in logic gave me my first real experience of intellectual muscle.

The demonstration that traces of sensory effect too slight to make any registry in consciousness could none the less influence judgment, may itself have been a persistent motive that induced me years later to undertake a book on The Subconscious."

Modern approaches to sensory perception, such as research on vision, hearing, or touch, measure what the perceiver's judgment extracts from the stimulus, often putting aside the question what sensations are being experienced.

Stevens revived the idea of a power law suggested by 19th century researchers, in contrast with Fechner's log-linear function (cf.

Although al-Haytham made many subjective reports regarding vision, there is no evidence that he used quantitative psychophysical techniques and such claims have been rebuffed.

The just-noticeable difference is not a fixed quantity; rather, it varies depending on the intensity of the stimuli and the specific sense being tested.

[18] In discrimination experiments, the experimenter seeks to determine at what point the difference between two stimuli, such as two weights or two sounds, becomes detectable.

Absolute and difference thresholds are sometimes considered similar in principle because background noise always interferes with our ability to detect stimuli.

To avoid these potential pitfalls, Georg von Békésy introduced the staircase procedure in 1960 in his study of auditory perception.

[22] In this method, the observers themselves control the magnitude of the variable stimulus, beginning with a level that is distinctly greater or lesser than a standard one and vary it until they are satisfied by the subjective equality of the two.

The difference between the variable stimuli and the standard one is recorded after each adjustment, and the error is tabulated for a considerable series.

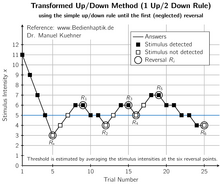

Adaptive staircase procedures (or the classical method of adjustment) can be used such that the points sampled are clustered around the psychometric threshold.

Data points can also be spread in a slightly wider range, if the psychometric function's slope is also of interest.

Bayesian methods take the whole set of previous stimulus-response pairs into account and are generally more robust against lapses in attention.

If the participant makes the correct response N times in a row, the stimulus intensity is reduced by one step size.

The choice of the next intensity level works differently, however: After each observer response, from the set of this and all previous stimulus/response pairs the likelihood is calculated of where the threshold lies.

Magnitude estimation generally finds lower exponents for the psychophysical function than multiple-category responses, because of the restricted range of the categorical anchors, such as those used by Likert as items in attitude scales.