Public health emergency of international concern

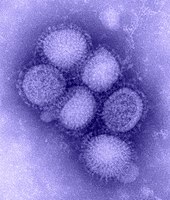

[1] Automatically, SARS, smallpox, wild type poliomyelitis, and any new subtype of human influenza are considered as PHEICs and thus do not require an IHR decision to declare them as such.

The first is the delay between the first case and the confirmation of the outbreak by the healthcare system, allayed by good surveillance via data collection, evaluation, and organisation.

[4] The declaration is promulgated by an emergency committee (EC) made up of international experts operating under the IHR (2005),[3] which was developed following the SARS outbreak of 2002–2003.

[17]This definition designates a public health crisis of potentially global reach and implies a situation that is "serious, sudden, unusual, or unexpected", which may necessitate immediate international action.

[19][20] Under the IHR (2005), ways to detect, evaluate, notify, and report events were ascertained by all countries in order to avoid PHEICs.

[19] SARS, smallpox, wild type poliomyelitis, and any new subtype of human influenza are always a PHEIC and do not require an IHR decision to declare them as such.

[13] ECs were not convened for the cholera outbreak in Haiti, chemical weapons use in Syria, or the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan, for example.

The director-general takes the advice of the EC, following their technical assessment of the crisis using legal criteria and a predetermined algorithm after a review of all available data on the event.

[11] The status achieved, as global eradication, was deemed to be at risk by air travel and border crossing overland, with small numbers of cases in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Nigeria.

[29] As of November 2021, taking into account recent events in Afghanistan, a large number of unvaccinated children, increasing mobile people in Pakistan and the risks associated with the COVID-19 pandemic among others, polio remains a PHEIC.

[13] On 1 February 2016, the WHO declared its fourth PHEIC in response to clusters of microcephaly and Guillain–Barré syndrome in the Americas, which at the time were suspected to be associated with the ongoing 2015–16 Zika virus epidemic.

[32] Later research and evidence bore out these concerns; in April, the WHO stated that "there is scientific consensus that Zika virus is a cause of microcephaly and Guillain–Barré syndrome.

[37] The advice against declaring a PHEIC in October 2018 and April 2019, despite the criteria for doing so appearing to be met on both occasions, has led to the transparency of the IHR EC coming into question.

[39][40] The conclusion was that while the outbreak was a health emergency in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and the region, it did not meet all the three criteria for a PHEIC.

[44] Acknowledging a high risk of spread to the capital of North Kivu, Goma, a call for a PHEIC declaration was published on 10 July 2019 in The Washington Post by Daniel Lucey and Ron Klain (the former United States Ebola response coordinator).

The risk of the disease moving into nearby Goma, Congo—a city of 1 million residents with an international airport—or crossing into the massive refugee camps in South Sudan is mounting.

[54][55] Previously, the WHO had held EC meetings on 22 and 23 January 2020 regarding the outbreak,[56][57][58] but it was determined at that time that it was too early to declare a PHEIC, given the lack of necessary data and the then-scale of global impact.

[53] In September 2022, the Lancet commission on COVID-19 published a report, calling the response to the pandemic "a massive global failure on multiple levels".

[72][73] The WHO responded by noting "several key omissions and misinterpretations in the report, not least regarding the public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) and the speed and scope of WHO's actions.

"[72] The formal end of the COVID-19 PHEIC is a matter of much nuance which carries its own risks, and as of March 2023, "WHO member states are negotiating amendments to the International Health Regulations as well as a new legally binding agreement (most likely a treaty) on pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response.

[80] The WHO had previously held an EC meeting on 23 June 2022 regarding the outbreak, which had more than 2,100 cases in over 42 countries at that point; it did not reach the criteria for a PHEIC alert at the time.

Severe outbreaks, or those that threatened larger numbers of people, did not receive a swift PHEIC declaration, and the study hypothesized that responses were quicker when American citizens were infected and when the emergencies did not coincide with holidays.

[88][89] Originating in Saudi Arabia, MERS reached more than 24 countries and resulted in 876 deaths by May 2020,[90][91] although most cases were in hospital settings rather than sustained community spread.