Publication of Domesday Book

A digital edition of manuscript facsimile images alongside the text of the Phillimore translation was published as the "Domesday Explorer" on CD-ROM in 2000, publicly accessible as an online database since 2008.

[2] The Society struggled to achieve its aims, however, being afflicted by its members' limited resources and sheer lack of enthusiasm.

[5] In March 1767 Charles Morton (1716–1799), a librarian at the British Museum, was put in charge of the scheme; a fact which caused resentment towards him from Abraham Farley, a deputy chamberlain of the Exchequer who for many years had controlled access to Domesday Book in its repository at the Chapter House, Westminster, and furthermore had been involved in the recent Parliament Rolls printing operation.

[8] Farley pursued the task with a single-minded devotion born of long involvement with the public records, and Domesday Book in particular.

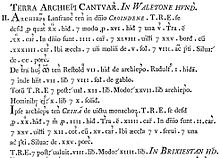

One of his closest associates during the project was the printer John Nichols, inheritor of William Bowyer's London printing press, who in 1773 had developed the special "record type" typeface that was used in the published edition to represent as closely as possible the script in Domesday Book itself.

These were compiled under the direction of Sir Henry Ellis and published in 1816, together with an edition of four "satellite surveys" – the Exon Domesday, the Liber Winton, the Inquisitio Eliensis and the Boldon Book.

The process involved the transferring of a photograph onto zinc or stone, which could then be used directly for printing or, alternatively, onto the waxed surface of a copper plate where the image formed a guide for engraving.

In a letter to the assistant Secretary to the Treasury, George Hamilton in October 1860, James outlined the cost of a complete reproduction of Domesday Book as an estimated £1575 for 500 copies or, alternatively, £3.

Newspapers such as the Photographic News reported on the events surrounding the invention and even supplied their readers with an example of a document which had undergone the process.

From the outset, it was intended that this plan should include English translations of the relevant county sections of the Domesday Book, with a scholarly introduction and a map.

Although the Phillimore edition rapidly became the most readily accessible and widely used version of Domesday Book, scholars criticised the translation for over-simplifying complex historical concepts: David Bates, for example, described it as "unconvincingly and unhelpfully 'modern'".

It has been called an "indecently exact facsimile" by Professor Geoffrey Martin, then Keeper of Public Records and custodian of the original Domesday.

[19] In order to produce this extremely high quality reproduction, the original Domesday Book was unbound to allow each page to be photographed.

The camera used for this process was the same size as a Ford Fiesta,[citation needed] and for security reasons was only operated in a sealed cage.

The Penny Edition was printed on a specialist paper made from cotton from the American Deep South to give something of the same weight and feel as the parchment of the original.

The editorial board, consisting of Ann Williams (editor-in-chief), G. H. Martin (general editor), J. C. Holt, Henry R. Loyn, Elizabeth Hallam-Smith (Assistant Keeper of Public Records), and Sarah Tyacke (Keeper of Public Records, the National Archives) produced a rigorously standardized and corrected translation based on the VCH text.

Penguin Books reproduced the Alecto translation in a single volume, published in 2002 in hardback and in 2003 in paperback, with an introduction by G. H. Martin.