Pugachev's Rebellion

It began as an organized insurrection of Yaik Cossacks headed by Yemelyan Pugachev, a disaffected ex-lieutenant of the Imperial Russian Army, against a background of profound peasant unrest and war with the Ottoman Empire.

After initial success, Pugachev assumed leadership of an alternative government in the name of the late Tsar Peter III and proclaimed an end to serfdom.

They would also enjoy religious freedoms and Pugachev promised to restore the bond between the ruler and the people, eradicating the role of the noble as the intermediary.

Even though Pugachev was illiterate, he recruited the help of local priests, mullahs, and starshins to write and disseminate his "royal decrees" or ukases in Russian and Tatar languages.

He promised to grant to those who followed his service land, salt, grain, and lowered taxes, and threatened punishment and death to those who didn't.

For example, an excerpt from a ukase written in late 1773: From me, such reward and investiture will be with money and bread compensation and with promotions: and you, as well as your next of kin will have a place in my government and will be designated to serve a glorious duty on my behalf.

If there are those who forget their obligations to their natural ruler Peter III, and dare not carry out the command that my devoted troops are to receive weapons in their hands, then they will see for themselves my righteous anger, and will then be punished harshly.

The priests would also be instructed to read Pugachev's manifestos during mass and sing prayers to the health of the Great Emperor Peter III.

"[Zubarev], believing in the slander-ridden decree of the villainous-imposter, brought by the villainous Ataman Loshkarev, read it publicly before the people in church.

And when that ataman brought his band, consisting of 100 men, to their Baikalov village, then that Zubarev met them with a cross and with icons and chanted prayers in the Church; and then at the time of service, as well as after, evoked the name of the Emperor Peter III for suffrage."

Author's translation) Pugachev's army was composed of a diverse mixture of disaffected peoples in southern Russian society, most notably Cossacks, Bashkirs, homesteaders, religious dissidents (such as Old Believers) and industrial serfs.

The heterogeneous population in Russia created special problems for the government, and it provided opportunities for those opposing the state and seeking support among the discontented, as yet unassimilated natives.

They followed the promises of Pugachev and raised the standard of revolt in the hope of recapturing their previous special relationship and securing the government's respect for their social and religious traditions.

The Russian general Michelson lost many men due to a lack of transportation and discipline among his troops, while Pugachev scored several important victories.

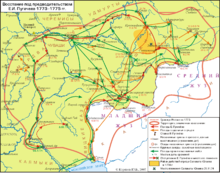

He had a substantial force composed of Cossacks, Russian peasants, factory serfs, and non-Russians with which he overwhelmed several outposts along the Iaik and early in October went into the capital of the region, Orenburg.

While besieging this fortress, the rebels destroyed one government relief expedition and spread the revolt northward into the Urals, westward to the Volga, and eastward into Siberia.

Though beaten three times at Kazan by tsarist troops, Pugachev escaped by the Volga, and gathered new forces as he went down the west bank of the river capturing main towns.

The Mordovians, Mari, Udmurts, and Chuvash (from the Volga and Kama basin) for example, joined the revolt because they were upset by Russian attempts to convert them to Orthodoxy.

[citation needed] Because the natives professed allegiance to Pugachev, the rebel leader had no choice but to implicitly condone their actions as part of his rebellion.

In spite of their integral role, Bashkirs fought for different reasons than many of the Cossacks and peasants, and sometimes their disparate objectives disrupted Pugachev's cause.

While the Bashkirs had a clear unified role in the rebellion, the Buddhist Kalmyks and Muslim Kazakhs, neighboring Turkic tribes in the steppe, were involved in a more fragmented way.

He cites the Kalmyk campaign led by II'ia Arapov which, though defeated, caused a total uproar and pushed the rebellion forward in the Stavropol region.

While there were many who believed Pugachev to be Peter III and that he would emancipate them from Catherine's harsh taxes and policies of serfdom, there were many groups, particularly of Bashkir and Tatar ethnicity, whose loyalties were not so certain.

Pugachev's followers idealized a static, simple society where a just ruler guaranteed the welfare of all within the framework of a universal obligation to the sovereign.

Such a frame of mind may also account for the strong urge to take revenge on the nobles and officials, on their modern and evil way of life.

The absence of an independent Russian press at the time, particularly in the provinces, meant that foreigners could read only what the government chose to print in the two official papers, or whatever news they could obtain from correspondents in the interior.

(Alexander, 522) Russian government undertook to propagate in the foreign press its own version of events and directed its representatives abroad to play down the revolt.

As Catherine said "I consider the weak conduct of civil and military officials in various localities to be as injurious to the public welfare as Pugachev and the rabble he has collected.

The most crucial lesson Catherine II drew from the Pugachev rebellion, was the need for a firmer military grasp on all parts of the Empire, not just the external frontiers.

The revolt did occur at a sensitive point in time for the Russian government because many of their soldiers and generals were already engaged in a difficult war on the southern borders with Ottoman Turkey.