Pulqueria

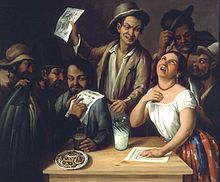

They were associated with extravagant decorations and names, social drinking, music, dancing, gambling, fighting, crime, and sexual promiscuity.

Central to daily life and culture in Mexico, government authorities throughout history generally saw them as threats to the social order and the progress of the nation.

"[4] With a tool that looks like a spoon and is called a tlaquiche, a worker known as a tlachiquero "scrapes off the center of the plant to extract the liquid previously mentioned.

[4] Pulque has been drunk in the lands of central Mexico and other parts of Mesoamerica since before the times of the Aztecs, who regarded the maguey plant as a divine gift.

[4] Other more "ordinary" people who drank pulque more frequently were the elderly, the sick, and pregnant women, because of the belief that the drink had healing powers.

"[4] When drinking pulque during Aztec times, it was also required to pour some of the beverage on the ground, typically at the four sides of the room a person was in.

As one myth goes, the god Quetzalcoatl was tricked into getting intoxicated by drinking pulque and had sexual relations with a celibate priestess (in other tellings, it was his sister, the goddess Quetzalpetlatl).

[6] The mural "portrays a feasting scene with figures wearing elaborate turbans and masks, drinking pulque and performing other ritual activities.

As the outdoor stands evolved to serve more customers, they built walls and ceilings for protection from the elements, and later to help hide them from public view.

However, for the elite upper classes, the government, and the Church, the popularity of the pulqueria was seen as a "threat to the social order and the status quo" of the cities.

[9] For these groups of higher social standing, pulquerias represented laziness, animalistic sexuality, and general degenerative behavior preventing societal progress.

The Spanish authorities enacted new rules and regulations in the late 1600s to limit the number of pulquerias, to allow fewer and smaller storage rooms for extra pulque, and to completely eliminate seating.

Pulquerias and what they represented continued to be a major source of contention between the Spanish ruling class and the urban masses throughout the Bourbon period until Mexico gained independence in 1821.

This was because of the lack of strong central government in the newly independent state, as well as the political and economic advantages that local governors saw in this well-established institution.

They not only told the customers what to expect from that particular establishment, but also made references to popular literature, the theater, as well as international figures or events.

Opera titles such as Norma, Semiramide, and La Traviata were in use, as were literary figures, Don Quixote and The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, among others.

[17] Many of the names written on the walls of the outside of the pulquerias were misspelled,[17] which is thought to be a testimony to the low literacy rates in Mexico at the time.

The day's delivery of pigskin sacks of pulque in carts pulled by donkeys or mules arrive at the pulquerias by eight or nine in the morning.

Then the cooks would start preparing the different dishes customers would order later that day, including enchiladas, quesadillas, tacos, tostados, sopes, mole poblano, chalupas, and others.

So around the turn of the twentieth century there was an increase in the number of reforms and regulations centered on limiting the distribution of pulque, and supervising the use and role of pulquerias.

Overall, the Porfirian reforms enacted to directly limit the influence of pulquerias during the Porfiriato did not do much to reduce their popularity in Mexico City and the rest of the country.