Pulse-Doppler radar

The first operational pulse-Doppler radar was in the CIM-10 Bomarc, an American long range supersonic missile powered by ramjet engines, and which was armed with a W40 nuclear weapon to destroy entire formations of attacking enemy aircraft.

Pulse-Doppler radar was developed during World War II to overcome limitations by increasing pulse repetition frequency.

Early pulse-dopplers were incompatible with other high power microwave amplification devices that are not coherent, but more sophisticated techniques were developed that record the phase of each transmitted pulse for comparison to returned echoes.

Early examples of military systems includes the AN/SPG-51B developed during the 1950s specifically for the purpose of operating in hurricane conditions with no performance degradation.

Pulse-Doppler radar is based on the Doppler effect, where movement in range produces frequency shift on the signal reflected from the target.

A one degree antenna beam illuminates millions of square feet of terrain at 10 miles (16 km) range, and this produces thousands of detections at or below the horizon if Doppler is not used.

Non-Doppler radar systems cannot be pointed directly at the ground due to excessive false alarms, which overwhelm computers and operators.

An MTI antenna beam is aimed above the horizon to avoid an excessive false alarm rate, which renders systems vulnerable.

Pulse-Doppler provides an advantage when attempting to detect missiles and low observability aircraft flying near terrain, sea surface, and weather.

Audible Doppler and target size support passive vehicle type classification when identification friend or foe is not available from a transponder signal.

Medium pulse repetition frequency (PRF) reflected microwave signals fall between 1,500 and 15,000 cycle per second, which is audible.

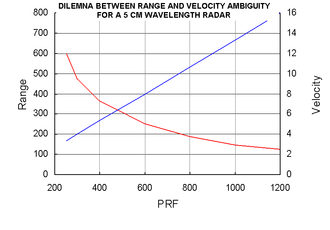

[citation needed] Ambiguity processing is required when target range is above the red line in the graphic, which increases scan time.

Scan time is a critical factor for some systems because vehicles moving at or above the speed of sound can travel one mile (1.6 km) every few seconds, like the Exocet, Harpoon, Kitchen, and air-to-air missiles.

The maximum time to scan the entire volume of the sky must be on the order of a dozen seconds or less for systems operating in that environment.

Search radar that include pulse-Doppler are usually dual mode because best overall performance is achieved when pulse-Doppler is used for areas with high false alarm rates (horizon or below and weather), while conventional radar will scan faster in free-space where false alarm rate is low (above horizon with clear skies).

The signal processing enhancement of pulse-Doppler allows small high-speed objects to be detected in close proximity to large slow moving reflectors.

To achieve this, the transmitter must be coherent and should produce low phase noise during the detection interval, and the receiver must have large instantaneous dynamic range.

This creates a transmit pulse with smooth ends instead of a square wave, which reduces ringing phenomenon that is otherwise associated with target reflection.

Mechanical RF components, such as wave-guide, can produce Doppler modulation due to phase shift induced by vibration.

This introduces a requirement to perform full spectrum operational tests using shake tables that can produce high power mechanical vibration across all anticipated audio frequencies.

Start of receiver sampling needs to be postponed at least 1 phase-shifter settling time-constant (or more) for each 20 dB of sub-clutter visibility.

Refraction for over-the-horizon radar uses variable density in the air column above the surface of the earth to bend RF signals.

The pulse-Doppler radar equation can be used to understand trade-offs between different design constraints, like power consumption, detection range, and microwave safety hazards.

The value D is added to the standard radar range equation to account for both pulse-Doppler signal processing and transmitter FM noise reduction.

Track mode works like a phase-locked loop, where Doppler velocity is compared with the range movement on successive scans.

Special consideration is required for aircraft with large moving parts because pulse-Doppler radar operates like a phase-locked loop.

Microwave Doppler frequency shift produced by reflector motion falls into the audible sound range for human beings (20–20000 Hz), which is used for target classification in addition to the kinds of conventional radar display used for that purpose, like A-scope, B-scope, C-scope, and RHI indicator.

A special mode is required because the Doppler velocity feedback information must be unlinked from radial movement so that the system can transition from scan to track with no lock.

Similar techniques are required to develop track information for jamming signals and interference that cannot satisfy the lock criterion.

Tracking will cease without this feature because the target signal will otherwise be rejected by the Doppler filter when radial velocity approaches zero because there is no change in frequency.